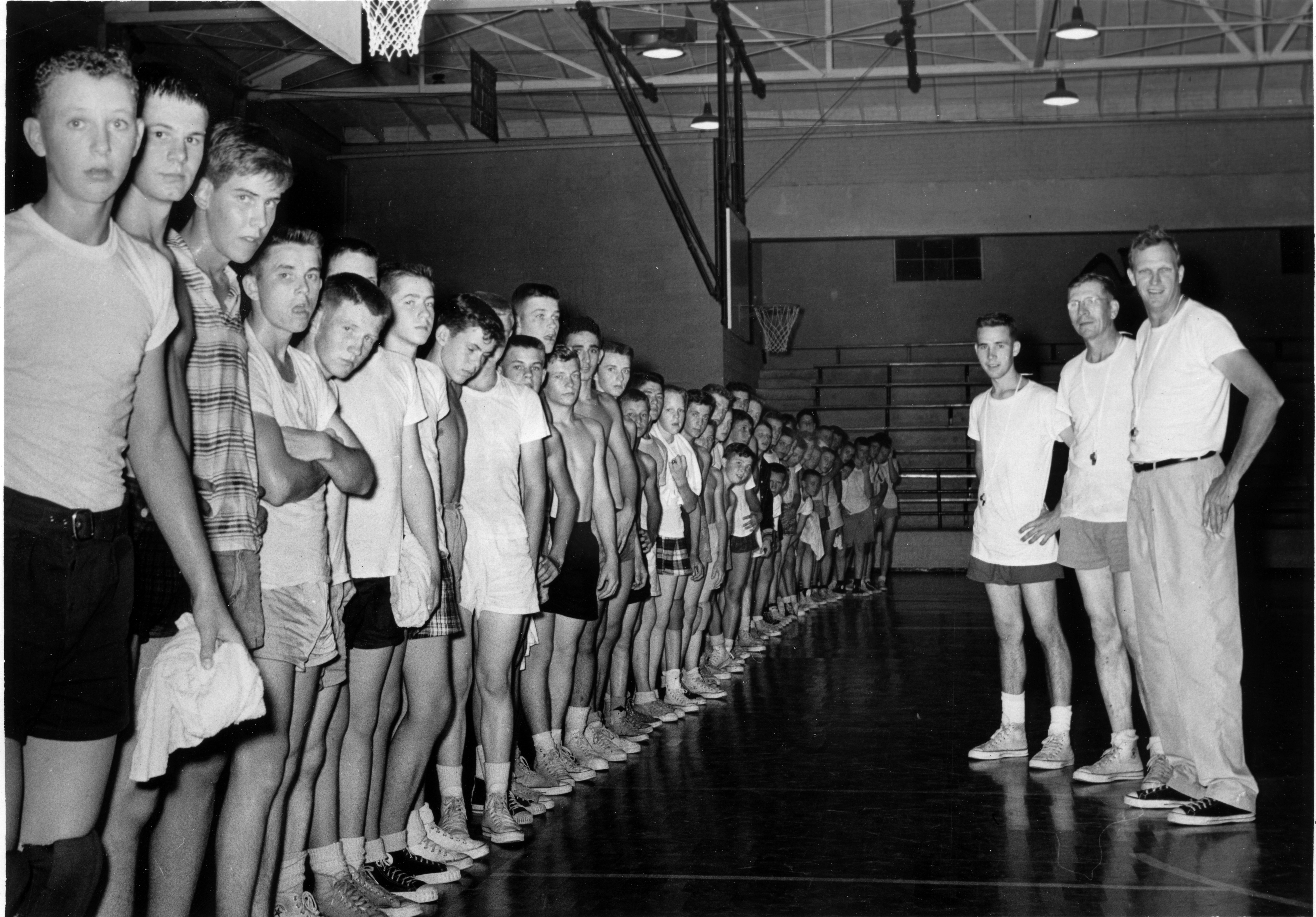

Fred & bones

Fred McCall needed a name to get his big idea off the ground. He got that and more in Bones Mckinney.

He was a bull of a man, 6-foot-2, 240 pounds, his hairline long gone by his 30s. He was a stickler for the fundamentals of basketball (and life) who rarely uttered a word of profanity.

His partner was tall and lanky enough to earn the nickname “Bones.” His head was crowned with wavy locks of autumn gold hair. Despite being an ordained minister, he was a loose cannon who admitted to cussing out and threatening the lives of several hundred referees.

They were a motley pair, Fred McCall and Horace “Bones” McKinney, but if Campbell Basketball School was ever to succeed, they, together, had to make it work.

McCall came to Campbell in 1953, the same year the college opened Carter Gymnasium, and was an instant success, compiling a 63- 11 record in his first three years and winning a pair of state junior college championships in the process. After that third year, McCall — a great athlete in his own right, lettering in football, basketball and baseball at Lenoir Rhyne (fighting in the Philippines in WWII in the process) — followed through on an idea to start a summertime basketball camp for boys.

His camp would serve two main purposes. First, and most importantly, it would bring in teens and preteens hungry for knowledge of basketball, a sport growing by leaps and bounds in popularity in the 1950s thanks to stars like Bill Sharman, Dolph Schayes and Bob Cousy. Second, it would give basketball coaches something to do — and perhaps a few extra bucks — during the summer months when many of them had to find other work to make ends meet.

“He knew he had a great idea, but he knew for it to be successful, he had to have a name associated with it,” said Leah Devlin, McCall’s daughter and former North Carolina state health director. “He called Bones McKinney and said, ‘You’re a name. I’m not. Will you partner with me?’ The two then became friends for life.”

In 1956, Bones was coach at Wake Forest University, where he’d become an even bigger North Carolina legend with a Final Four appearance in 1962. He’d already made a name for himself by being the rare basketball player to have suited up for both N.C. State and UNC-Chapel Hill (he fought in the war between playing stints and led the Tar Heels to the 1946 Final Four). He played six seasons in the NBA with the Washington Capitols and Boston Celtics before retiring in ‘52.

McCall’s idea worked. His little rural basketball camp drew about 150 campers that first year, split into groups of 75 for two weeks. Cost to attend was $25 a camper, a rate that would go up to $29.50 by 1960.

McCall and McKinney joined five other coaches for that first camp and split the boys into groups of 25 for three stations — the new Carter Gym, the old gymnasium on campus and the high school in Lillington, accessed by an old bus driving by Coach Hoggie Davis. Each station featured a specific fundamental of the game, from shooting to rebounding, passing to defense.

“He was a basketball genius,” said Danny Roberts, who joined McCall’s staff at Campbell in the early 60s and eventually succeeded him as head coach in ‘69. “We

did drills that nobody else in the world was doing. When I played for him, he had us climbing over rails, crawling on the floors and even slapping each other to get tough. And he’d run you to death, too. But we learned a great deal from him, and so did those campers. He was very innovative.”

Not all the students were into it, McKinney recalled in his autobiography, “Honk if You Love Basketball.”

“During that first year, I taught pivot play,” Mckinney wrote. “My group was very small, and i could tell those youngsters weren’t too interested in pivot play. One little fella was standing off to the side, not talking or participating. I said, ‘Son, why did you come to the camp?’ he answered, ‘Mother and daddy wanted to go to the beach, and this was the cheapest place they could send me.’”

Word did spread quickly throughout the state and the East Coast about the new basketball school in the

middle of nowhere. Bones was teammates in his final year with the Celtics with a young up- and-comer named Bob Cousy. In 1957, Cousy had just won his first of six NBA championships and was the league’s MVP and All-Star Game MVP. “Mr. Basketball” was one of the first “big names” to lend his celebrity to Campbell’s camp. Schayes and Sharman showed up, too, giving for more respectability and marketing to the camp than McCall ever dreamed.

Each June brought in more big names — none bigger than Coach John Wooden in 1966, who’d already won two of his 10 national titles at UCLA by the time he first stepped foot inside Carter Gym. Wooden found out about the camp through Bones (coaching Wake Forest at the time) whom Wooden bested in recruiting the nation’s best high school big man, Lew Alcindor (a.k.a. Kareem Abdul-Jabbar) the previous year. Wooden accepted the invitation to Buies Creek after receiving a call from McCall. From there, another frienship blossomed.

“John Wooden loved my father,” Devlin recalled. “Outside of the camp, they became genuine friends. He always remembered my family at Christmas and on birthdays. There wasn’t a kinder, nicer man around.”

The camp was drawing more than 1,000 kids by the late 60s, and every June, Campbell College was drawing more than just kids and big name counselors and instructors. It was drawing media coverage never before seen in Buies Creek. TV cameras and reporters from multiple states were taking advantage of the impressive gatherings, and eventually, the camp’s press conferences became as common as the morning convocation.

In 1969, in the middle of his 16th season as Campbell’s head basketball coach, McCall was approached by Campbell President Norman A. Wiggins with an offer to become the school’s first vice president of advancement. McCall had turned down higher-paying coaching positions at big-name schools because of his love for Campbell and Buies Creek in the past, but this was his first offer to leave the sport he loved.

Challenged with the task of developing a new giving program at the school, McCall accepted the job and traded in his whistle for a tie.

“It was a hard decision to leave the bench,” his daughter said. “But he was devoted and loyal to Dr. Wiggins and Dr. [Leslie] Campbell before him. Campbell was his life. He would do anything for the school.”

McCall transitioned into the role of VP seamlessly. His skills as a recruiter came in handy in building better alumni relations and fundraising. McCall would serve Campbell a total of 33 years, guiding the men’s basketball team to a 221-104 record for 16 of those years and helping guide Campbell from a college to a university as a vice president before his retirement in 1986. He was inducted into the North Carolina Sports Hall of Fame in 1994 and the Campbell Athletics Hall of Fame in ‘95.

His friend Bones McKinney, once called the “Forrest Gump” of basketball for his ability to be around for some of the sport’s greatest moments, died in 1997. McCall passed away in 2008 at the age of 85.

Wooden — the man considered by many to be the greatest coach and one of the most inspirational sports figures of all time — once called Fred McCall one of the finest men he’s ever known.

“He’s a wonderful person in every respect,” he told The News & Observer.

“He believed fundamentals in sports translated into everyday life,” said Devlin, today a trustee for the University her father loved. “Hard work, team building, discipline, practice, leadership. Sharing glory and sharing pain. The lessons learned in team sports helped shape young men and women for real life. My father taught this to thousands of young men and women.”