The Wizard

The greatest basketball coach in the world fell in love with Campbell, its camp and its people.

The book is barely larger than a legal pad. Its hardbound cover is free of words or pictures. And its location — in the far reaches of Wiggins Memorial Library, tucked away on the fourth floor among other sports-related biographies — does nothing to suggest its huge historical significance to Campbell University.

But open the book, and it hits you. In dark blue, loopy cursive writing reads four words

The Wizard of Westwood. The greatest coach in the history of college basketball. Winner of seven consecutive national titles and 10 in 12 years at UCLA. Winner of a record 88 consecutive games. Basketball’s first Hall of Famer as both a player and coach. Creator of the “Pyramid of Success.”

The “Greatest Coach of All Time in Any Sport,” The Sporting News recently crowned him.

Unknown to the rest of the world, but a pride point in these parts, was Wooden’s love for Buies Creek, North Carolina. He was an avid believer of and regular participant in the Campbell Basketball School.

For 11 years — during the peak of his college basketball dominance from the mid-1960s

to the mid-70s — Wooden took a break from his busy schedule every June to spend

a week in Buies Creek. Usually wearing a white UCLA polo, coach shorts and a whistle, Wooden spent his days and his nights at Campbell, speaking and teaching in the same high school gyms as the other instructors and eating in Marshbanks Cafeteria like anyone else.

“He didn’t just come in and talk to the kids for 45 minutes and leave,” the Fayetteville Observer’s Khary McGhee wrote in 2003 for a column on the 50th anniversary of the first camp. “He stayed here, stood in line in the cafeteria like the rest of us. He also played softball with the counselors in the evening after the basketball instruction was done.”

He became just one of the guys, said Caulton Tudor, who first met Wooden as a young man attending the camps and later in life as a sports writer/columnist for the Raleigh News & Observer.

“He just loved Buies Creek. He loved the village-like atmosphere,” Tudor said. “At heart, he was still an Indiana farm boy, and this area was such a far cry from Los Angeles and Buies Creek reminded him of where he grew up. He could have made millions with his own basketball camps, and he could have gone anywhere. But he came for this camp, and he just loved it.”

Tudor said Wooden first learned of Campbell through Wake Forest coach Horace “Bones” McKinney, who led his Demon Deacons to the Final Four in 1962, the same year Wooden’s Bruins made their first of 12 appearances (both teams lost in the semifinals, and McKinney’s squad beat Wooden’s 82-80 in the third-place game).

Three years later, according to Tudor, the two coaches were locked in a recruiting battle to land the nation’s best big man, Lew Alcindor (later Kareem Abdul-Jabbar). Alcindor’s

final two choices coming out of high school were Wake and UCLA, and many told him to go east to play for McKinney, known at the time as the best coach for big men in the country. Alcindor instead chose Wooden, and the duo led UCLA to an 88-2 record in his three years there.

“Bones and Coach Wooden were good friends before that and even after,” Tudor said. “Not long after Alcindor [picked UCLA in 1965], Bones told him he needed to come to North Carolina and see this basketball camp Campbell had begun.”

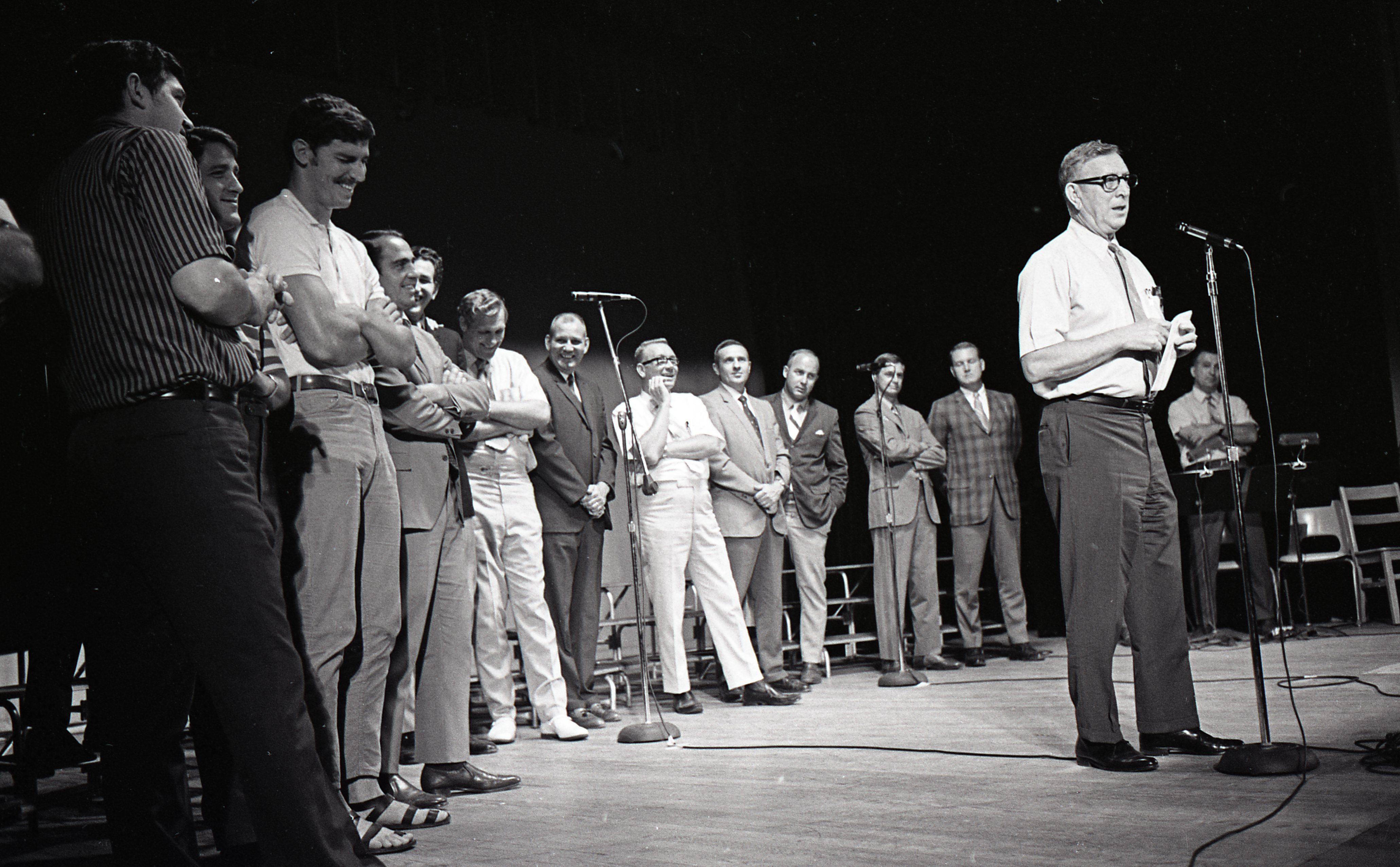

Wooden’s arrival provided an unneeded stamp of legitimacy to the camp, which was already enjoying increased attendance year after year by the time he arrived in ‘66, toward the beginning of his historic national championship run. The camp was already being run by the top coaches in the region, with counselors who made up the ACC’s best and brightest young stars assisting them. Even the big names had trouble, at times, getting their group’s attention.

But when Wooden spoke? Crickets.

“Us campers were a bunch of knucklehead kids,” wrote former camper Michael Hunt, who would go on to enjoy 35 years as a sports columnist in Milwaukee. “But when Wooden spoke, we all went silent, hanging on to his every word.”

“Man, we listened to every word,” said Fred Whitfield, former camper, counselor and Campbell stand-out, now president and chief operating officer of the NBA’s Charlotte Hornets. “You’d hear about Coach Wooden, and you knew his legacy coming in. But to see him in person at this camp in Carter Gym? Unbelievable.”

Whitfield said Wooden had a “calmness and demeanor” that drew the students in, but even the coaches — successful in their own right — gravitated toward him.

“I don’t use this word often, but he was almost God-like,” said one of those coaches, Danny Roberts, an assistant at Campbell from 1963-69 before succeeding Fred McCall as Campbell’s head coach. “We had coaches at this camp who swore a lot … used tons of profanity. But in front of Coach Wooden? Not a word. They were angels.”

Scott Colclough — former camper, Campbell alumnus and assistant basketball coach at UNC-Pembroke — remembered Wooden as a deeply religious man who never went anywhere without his Bible.

“And for all of his success and credentials, there wasn’t an ounce of arrogance in

the man,” Colclough said. “And for the other coaches, there was no animosity. No jealousy. Coach Wooden loved coming to Campbell because he really, really enjoyed the camaraderie. Yes, he liked the smallness of the campus and the town, but he also came back every year because he felt like one of the boys.”

“I really felt more at home there, to be honest with you, since it was a smaller community. Most of the other coaches there were from the smaller schools from the area, and I just felt more comfortable with them.”

In May 1973, Wooden accepted an honorary degree from Campbell College and spoke briefly at the commencement ceremony two months after winning his seventh consecutive national title. The occasion was significant because Wooden, though he had been offered similar

honors from countless schools over the years, accepted Campbell’s invitation and honorary Doctor of Humanities degree because of his respect for President Norman A. Wiggins and his love for the school.

“I have said before that I do not believe in honorary degrees, and I have refused them at some universities,” Wooden said at the time. “This is the first one I have accepted. That I chose to accept one here shows my feelings toward the people of Campbell College.”

Not that he didn’t make the most of his trip to North Carolina that spring. While in town, he negotiated a game with North Carolina State for the following season. UCLA and its 78-game winning streak at the time would face a Wolfpack team enjoying its own 29-game streak and embarrass them, 84-66 (N.C. State got its revenge that season in the Final Four).

Wooden quit coaching at the top of his game — announcing his retirement just before his 10th national title in 1977.

Tudor reached out to Wooden years later by phone and after introducing himself, told him he was once a young camper in the Campbell Basketball School — a note that landed him a few one-on-one interviews when Duke was on the road. The two would talk about Wooden’s Campbell days, and the old coach confided in Tudor that had things gone differently, he would have spent his retirement in Buies Creek.

“‘I loved that place. I always loved it,’” Tudor recalled Wooden telling him. “But he said Nell’s health started failing, and Harnett County wasn’t really known for

its health care system at the time. Raleigh was a good 40 miles away … too far for the Woodens at that time.”

Wooden’s wife, his rock, Nell Wooden died on March 22, 1985. After leaving the game, John stayed by her side during a lengthy illness, which included double hip replacement, two heart attacks and a 93-day coma.

The two had met in high school in Martinsville, Indiana, when John was a basketball star and she a trumpet player who “faked her way into the band” just to watch him play. Legend has it she marched with the team, holding the trumpet to her lips but never blowing a note.

An April 3, 1989, Sports Illustrated article on Wooden’s life after Nell detailed the coach and Nell’s pre-game ritual during his playing days:

“Before every tip-off back at Martinsville High, Wooden had looked up from his guard position and caught her eye in the stands, where she played the cornet in the band. She would give him the O.K. sign and he would wave back. They kept up that ritual even as Johnny Wooden (Hall of Fame, inducted as a player in 1960) became John R. Wooden (Hall of Fame, inducted as a coach in 1972). Few knew that he clutched a cross in his hand. Fewer knew that she clutched an identical one in hers. She took it with her to the grave.”

Wooden’s retirement also meant the end

of his involvement with Campbell. The Basketball School would enjoy continued success for another decade, partly because it was now the camp once regularly coached by the great John Wooden.

The Wizard’s impact on Campbell is most recognized in the memories and stories from those he coached and became true friends with — many in their 70s, 80s and 90s now — and the kids he taught.

Colclough points to an old photo of Wooden sitting at the base of a tree (the photo that begins this chapter) surrounded by young campers as the perfect representation of what he meant to not only the camp or the college, but the community.

“He enjoyed being around the kids,” Colclough said. “He enjoyed talking to them, learning about them and most of all, teaching them. He liked what this camp was all about … that it taught fundamentals and wasn’t just a babysitting camp. It was a true basketball school, and that’s what brought him back every year.”

Had Wooden stayed in North Carolina, perhaps it would be different. But today, there is no monument on Campbell’s campus observing the decade it hosted greatness. A trove of black and white photos and never-before-made-public negatives sit in a closet behind Campbell’s human resources office today, and a few old yearbooks and school newspapers tell little about the coach’s time here.

But the book sitting in Wiggins Library — plain, hardbound and full of wisdom, much like the man himself — remains. A personal, hand-delivered gift to a school he loved.