MY QUEST FOR THE TRUE ORIGIN OF ONE THE NATION’S MOST UNIQUE COLLEGE MASCOTS

By Billy Liggett

His deep sleep abruptly interrupted by a student at 3:30 a.m. on a cold December night in 1900, J.A. Campbell was soon running toward the flames that lit up the night sky in the distance. Sprinting toward the campus of the little academy he’d worked so hard to build over the previous 23 years, Campbell fell to his knees when he arrived. His campus was fully engulfed — falling to ashes before his eyes.

“There’s no chance to go on,” Campbell University’s founder and first president would later say.

And that’s where the legend begins.

In the days following, Campbell was distraught and rattled, his eyes red and puffy from the tears. For a short time, he refused to get out of bed.

Before long, Zachary Taylor Kivett — a self-taught architect and contractor who lived about six miles from Buies Creek Academy — attempted to console his dear friend. According to the late J. Winston Pearce, noted Campbell historian and author of two volumes of “Big Miracle at Little Buies Creek,” Kivett — “strong, tall, brusque, with deep and penetrating eyes — strode into the young schoolmaster’s bedroom and grasped his hand in sympathy and friendship.”

“Jim Archie, why are you in bed?” Kivett said. “Time’s wastin’. I thought Campbells had hump on them.”

The following month, the architect constructed a “shanty” for temporary classrooms until his grand achievement, Kivett Hall, was constructed in 1903. The building became a monument to the “love, loyalty and sacrifices” of the Campbell community, and today, still stands as Campbell’s iconic centerpiece. The phoenix that rose from the ashes. As for Kivett’s words of encouragement — “I thought Campbells had hump on them” — legend has it, this is the origin of the eventual mascot for the school. The Campbell Camels.

What a story. Dramatic, symbolic and downright suitable for a mascot as unique and beloved as ours.

It’s also very likely not the reason we’re the Campbell Camels.

There. I said it. A bold claim, I know.

(Deep breath).

I suppose I should explain.

It doesn’t help me at all that new President J. Bradley Creed — only the fifth president in Campbell’s 129-year history — passionately retold the Kivett story in his Installation Ceremony speech this spring. The story is a pride point for us. We’re the tiny school that nobody gave a chance during Civil War Reconstruction. We’re the school that made it to the turn of the century intact, only to crumble to the ground in a matter of hours. That we survived and flourished fits very well with the school motto, Ad Astra Per Aspera, “To the Stars Through Difficulties.”

So who am I to dispel the legend? Where do I get off trying to rewrite the already well-written history of Campbell?

I was inspired by an unlikely source — Auburn University. In that school’s Winter 2015 alumni magazine, alumnus Jeremy Henderson went out on a much longer limb than mine with his own quest for the truth behind Auburn’s storied “War Eagle” battle cry.

For nearly a century, Auburn — whose actual mascot is and has always been the Tiger — has explained the origin of “War Eagle” (chanted at every Auburn sporting event) through the story of a wounded eagle rescued from a Civil War battlefield by a Confederate veteran. That eagle, according to the story, triumphantly circled over Auburn’s first football game in 1892, inspiring the crowd and the team to victory.

What a story. And admittedly, it’s better than Campbell’s. But it seemed too good to be true to Henderson, who quoted the 1962 western, The Man Who Shot Liberty Valance, to explain the popularity of the legend — “When the legend becomes fact, print the legend.”

Campbell’s mascot legend isn’t entirely legend. Kivett did approach J.A. Campbell after the fire. He did encourage him to get up and get to work. And according to a letter Kivett wrote in 1923 recounting that fateful day, he most certainly did use that key word, “hump.”

But — and maybe this is the journalist in me — when presented with the idea that a mascot the school created in 1934 was the result of a private conversation 33 years earlier, I began to ask questions. For decades, Campbell was the Hornets, so why did it take so long to change the name? Why did the name change happen so unceremoniously? Why, when Pearce wrote about the Kivett-Campbell talk in his 1976 history book, did he not make the mascot connection?

My quest to answer these questions was frustrating, exhaustive and fascinating all at once. And it started with a thick stack of student newspapers from the 1930s in the dark recesses of the Carrie Rich Hall archive room.

Aside from the year Buies Creek Academy was founded in the late 1800s, 1934 stands as the most historic year in Campbell history.

On Jan. 13, a new dining hall (then called Leslie Campbell Hall, now referred to as Marshbanks) was dedicated — the ceremony marked the final public appearance by J.A. Campbell. On Feb. 14, the Campbell College basketball team won the Junior College Championship. A week later, a new bakery opened on campus. Later that year, the Paul Green Outdoor Theater (named for the Pulitzer Prize winner and 1918 Campbell grad) was dedicated.

On March 18, J.A. Campbell died in Fayetteville after a lengthy illness. Stories in the Creek Pebbles — the student newspaper — in the months leading up to his death chronicled his illness and return trips to the hospital. On March 29, his son Leslie was unanimously elected by the Board of Trustees to become J.A.’s successor as president. That September, Campbell enjoyed its largest enrollment, and a new student government association was started.

But before any of that — sometime between the Christmas break to end 1933 and the first week of classes in mid-January — the Campbell Hornets became the Campbell Camels.

We know this because in 1933, the football and basketball teams were going by the Hornets; and in 1934, headlines in the Creek Pebbles and other statewide publications began calling them the Camels. The only evidence that the name didn’t just magically appear came in the form of a small article on Page 3 of the Jan. 13, 1934, Creek Pebbles — “Camels” Initiate New Members. The article began, “Eight new men were recently initiated into Campbell’s Monogram Club, which has changed its name from ‘Hornets’ to ‘Camels.’”

And that’s it.

This coming from a paper that often launched into 200-word stories about the northerner who visited campus that day or 500-word columns about Erwin Royal and his propensity to sleep in on exam days couldn’t muster more than 20 words on something as significant as a mascot change. I looked other places as well. The Harnett County News had headlines like “Brother of Lillington woman dies in Florida,” but the school down the road adopting a new mascot never warranted a headline.

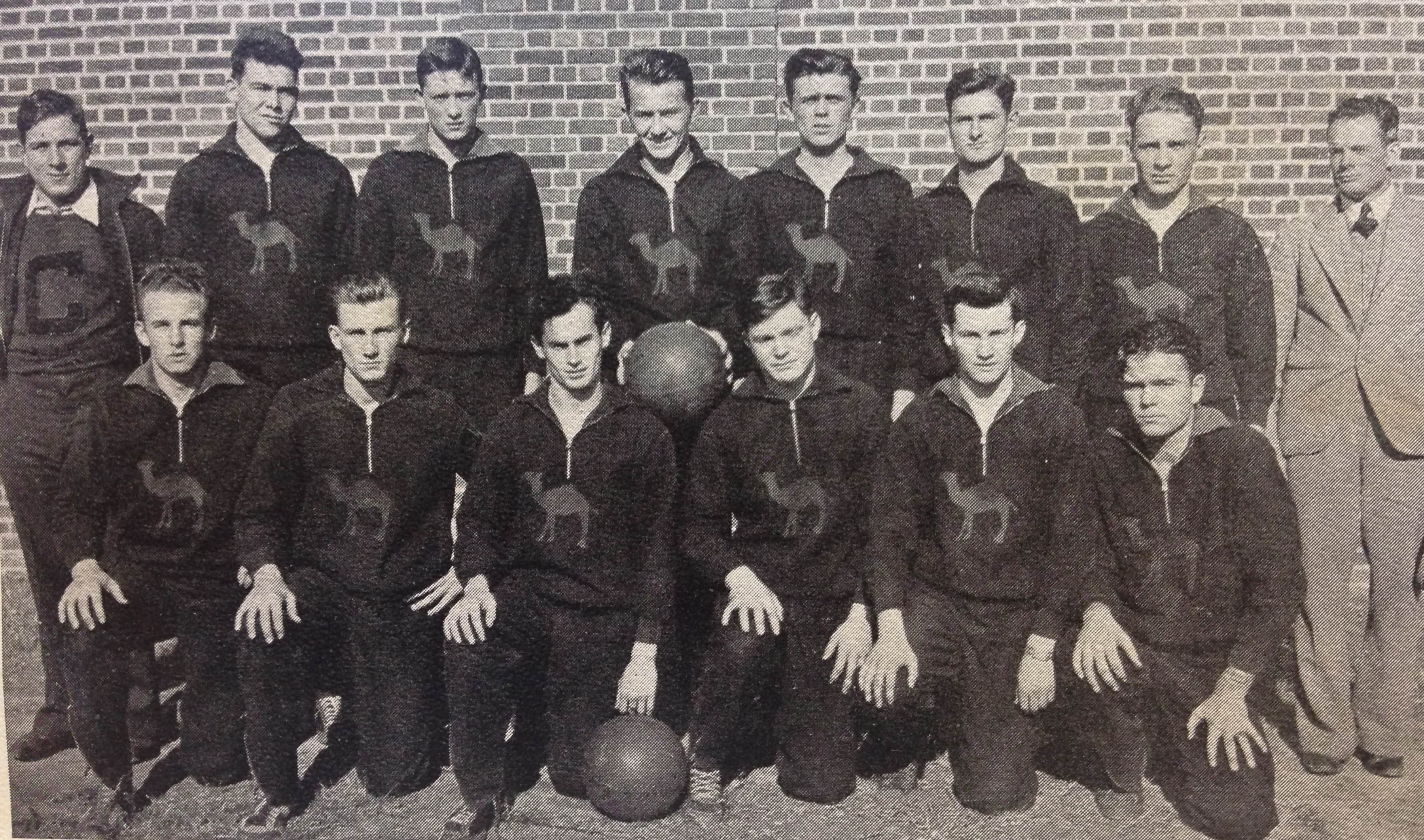

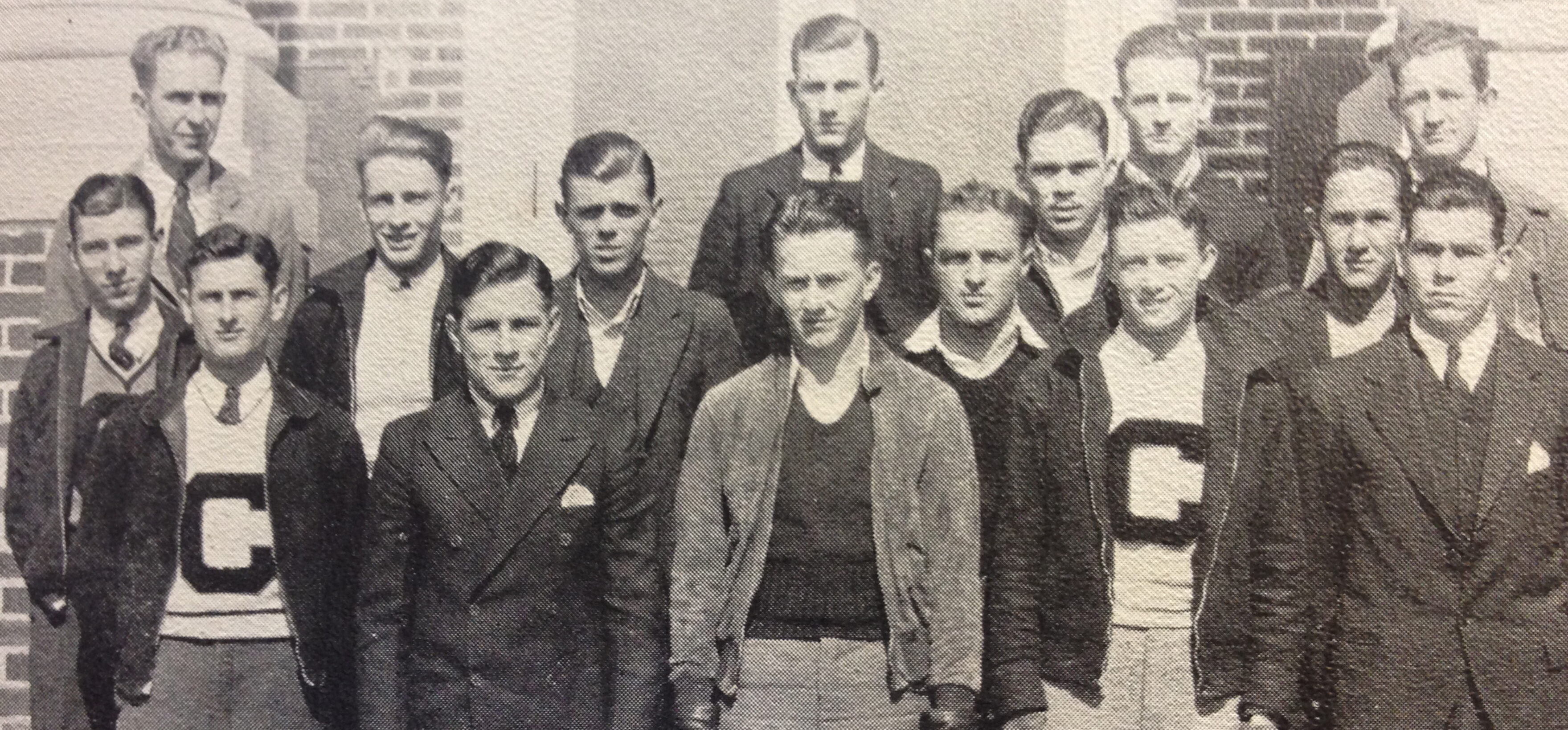

Campbell printed its “Book of Views” that spring — a skinnier alternative to the Pine Burr Yearbook because the school couldn’t afford the large printing costs for a few decades during the Great Depression and into World War II. The book contains the first visual evidence of the new mascot, a team photo of the junior college championship-winning men’s basketball team. The 12 square-jawed farm boys are sporting dark warm-up sweatshirts with the new camel logo on the front.

The Book of Views was light on words, so again, no explanation for the change. And it would be decades before any Campbell-affiliated publication would bring it up.

On Oct. 25, 1977, Creek Pebbles’ editors issued a challenge to their readers to find the truth behind the origin of the Camel (which means the Campbell-Kivett conversation had yet to become part of University lore).

“Many of you probably wonder why a wooly and awkward animal such as the camel could be chosen as our mascot,” one editor wrote. “No one — or no one we’ve interviewed — knows the true answer.”

Two weeks after the newspaper’s challenge, it published a front-page story by Ted Patterson with the headline, “Camel’s Origin Is Revealed.” Patterson interviewed the wife of legendary Campbell baseball coach Hargrove “Hoggie” Davis.

“This was her short but delightful story,” Patterson wrote before sharing the tale of Linda Bouldin, the former dean of women who was in charge of setting up floral arrangements for a banquet for Campbell’s female students. Bouldin’s son designed name plates for the girls and “thought long and hard” on an image to accompany those name plates.

“He derived, from the name Campbell, the word Camel,” the article explained.

The emblem made its way onto other designs and eventually stuck, Patterson wrote.

A delightful story, indeed. But also false — at least as an origin story.

In his article, Patterson dates Davis’ story to 1940 — six years after that secret Monogram Club meeting and the men’s basketball photo. And this story didn’t appear to satisfy those seeking the truth. On March 26, 1992, The Campbell Times (formerly Creek Pebbles) issued this front-page editor’s note: “Anyone knowing the truth behind the Camel legend and can show proof will receive a prize.”

It added, “If The Times cannot get the truth, we will award the prize to the most creative legend.”

How’s this for a creative legend?

D. Rich — you may recognize his name from the building at the centerpiece of the Academic Circle on campus — couldn’t sleep on the night of Sept. 26, 1923. He was in Buies Creek visiting his friend J.A. Campbell, whom he met a few years prior at a Baptist convention.

The reason for his insomnia: D. Rich couldn’t stop thinking about what more he could do to help the small school. The next morning, he told Campbell he had a talk with Jesus, who told him “Buies Creek must live.” He told Campbell that if he lived to get back home, he was going to change his will to see that the school survived.

D. Rich died a year later, leaving an eighth of his estate to Buies Creek Academy — $160,000 in cash. That enabled the construction of Kivett Hall’s neighbor, the D. Rich Memorial Building.

In his life, D. Rich contributed more than $400,000 to the school, which included funds for a library in his wife’s name, Carrie Rich Hall. He made his fortune in the tobacco industry, starting as a cashier and later becoming treasurer for R.J. Reynolds Tobacco Company, which by the 1920s was the top taxpayer in North Carolina and producer of two out of every three cigarettes made in the state.

R.J. Reynolds’ top brand, by a mile, was Camel.

It’s a crazy theory, I know, especially considering J.A. Campbell’s strict policies at his school, which included no profanity, no alcohol and no tobacco use on campus. In “Big Miracle,” Pearce wrote of J.A. Campbell’s father: “On the farm, the Campbells grew corn, wheat, oats, cotton and vegetables; [but] never tobacco, because he hated the ‘weed’ with a vehemence matching that which [J.A.] was to have.”

But consider the era — smoking was more than just socially acceptable behavior in the 20s and 30s … it was the norm. The percentage of young adults who smoked was on a sharp incline at this time and would peak in the 1950s. Camel Cigarette ads in the 30s informed the public that four out of every five doctors preferred their brand because it calmed the nerves or helped throat irritation.

And by 1934, Camel was a big player in the sports world. “They Don’t Get Your Wind” was a popular Camel ad campaign featuring New York Yankees legend Lou Gehrig; and between the 30s and 50s, Camel had other baseball and football players and even Olympic athletes promoting its brand.

Consider a few factors … again, purely speculation on my part. The mascot change came at a time when J.A. Campbell was mostly out of the public eye because of his health. Therefore, he probably wasn’t there to contest it. Remember, also, this was the Great Depression, and schools like Campbell were desparate to survive. Now go back to that 1934 men’s basketball group photo, and you’ll notice the camel on the warm-up uniforms is remarkably similar to the R.J. Reynolds’ Camel brand, which was immensely popular at the time. Would a tobacco company target an institution of higher education to market its brand?

I searched Trustee meeting records — some of them written by hand — during the era and found nothing from early 1934 and nothing even mentioning a mascot change. But an Aug. 29, 1940, assets list caught my eye as it showed Campbell College was owner of 3,622 shares of R.J. Reynolds stock, valued at $127,222.75. The figure made up more than 80 percent of the school’s total inventory value at the time.

If Campbell’s mascot history is tobacco-related, it explains the secrecy of the decision and the mystery surrounding the camel’s origins here. And even though tobacco and cigarettes are reaching taboo levels in society these days, if my theory is correct, then the camel suddenly has just as much state historical significance as the Tar Heel and Blue Devil mascots. And certainly more than the Wolfpack or the Demon Deacon.

But again … just a theory.

Except for a two-year stint of service during World War II, Burgess Marshbanks Jr. has lived all 93 years of his life in Buies Creek. He attended elementary school and college in Kivett Hall, and the dining hall dedicated during the year of the mascot change is named after his father, the former Campbell College treasurer.

He even remembers J.A. Campbell, who gave him a quarter when Marshbanks was a boy — “the most money I’d ever seen at the time, it being the Great Depression,” he recalls. “I thought I was really well off with a quarter.”

Burgess Marshbanks Jr. is a walking Campbell encyclopedia, a distinction he carries proudly. But even his pages are devoid of any history behind the origin of the Campbell Camel.

“You’ve asked me a question even I’d like to know,” he says after a few minutes of deep thought on the subject. “In fact, I barely remember we were the Hornets.”

I was able to reach out to Catherine Cheek Hall, a student at Campbell from 1934-36. She was the subject of a recent feature story in The Campbell Times, written by her great-great niece, Christian Hornaday. In the piece, Hall recalled working and saving $700 to pay for school, the dorm mother who watched her and her friends like a hawk when they talked to boys, and the pall cast over the school in the months following the death of its founder. She also shared the story of meeting her husband, Cullen Hall, and sharing their first kiss on the steps of the library after graduation.

But she had no recollection of the mascot change during her freshman year 82 years ago. Nor should she have. It didn’t hurt to ask.

Catherine Cheek Hall died two weeks after she was approached with the camel question. She would have turned 101 this August.

And thus presents the biggest hurdle I’ve had in chasing this legend. Eighty-two years later, there are but a handful of students from that time alive today. Even Marshbanks was only 8, going on 9, in 1934.

Going back to that 1992 announcement in The Campbell Times searching for “the truth” or “the most creative legend,” I failed to mention the article attached to that call-to-action. That year marked a renaissance in the camel’s popularity, both on campus and nationally, thanks to the men’s basketball team’s first and only appearance in the NCAA Tournament. As Campbell faced eventual champion Duke in the first round, several publications were focused more on Campbell’s unique mascot than the team that had no chance of knocking off Duke.

That March, two student writers — Rexanne Hege and Gretchen Orr — asked the question I’m asking and found a goldmine of a source in Gladys Satterwhite.

Satterwhite was a longtime English professor at Campbell, co-founder of its Epsilon Pi Eta honor society in the 20s, and she was Creek Pebbles adviser in the 30s and 40s. Satterwhite was 87 when approached by Hege and Orr, and her memory of the change seemed pretty clear in the article. Camels, she said, represented a symbolic change for the school — hornets stung and had an overall negative connotation. Camels, on the other hand, could go a long time without water. And during the Great Depression, Campbell and its students “had to go a long time without money.”

Satterwhite’s other explanation came down to simple alliteration. “Camels fit with Campbell,” she said. “They sounded alike.”

It’s an origin supported by another walking Campbell encyclopedia, Dorothea Stewart- Gilbert, a 1946 Campbell graduate and Buies Creek native who was 7 when the camel was born. The current director and curator for the Lundy-Fetterman Museum and Campbell Heritage Room said “Campbell Camels” just sounded better. Many in these parts pronounced the two words the same anyway, so it was a perfect fit.

Almost everybody.

“There was a professor here who would pronounce it ‘Camp. Bell. Mmmm,” she says with a disapproving shake of the head. “We told her she had to stop that.”

The harrowing tale of the wounded Civil War eagle flying high above a football stadium and inspiring the Auburn Tigers to victory was 100-percent made-up, it turns out. In his research, Henderson discovered the story’s origin was the result of an old April Fool’s column by a student writer that the school paper actually published in March.

The real origin of War Eagle is less dramatic — the star football player in 1912 was Auburn’s quarterback and punter, Rip Major, who had a ritual of yelling “War Eagle!” on the field before and during games. The chant caught on “for reasons we may never know,” Henderson wrote.

The Civil War story may have been debunked, but it’s better than the truth. And I’m sure it will resurface and remain Auburn’s origin story for decades to come.

After my search, that’s the way I feel about the origin of the Campbell Camel.

Whether it’s alliteration, a symbol of the Great Depression or a secret handshake agreement between a struggling school and a rich tobacco company — there is no (pardon the pun) smoking gun out there with a definitive answer.

Despite my best efforts, Kivett’s hump lives on.

So does my search for the truth.