Cary Kolat ruled the wrestling world in the 1990s before a disappointing end to his career at the Olympics in 2000. At Campbell, he’s out to prove he can lead another small program to an All-American level.

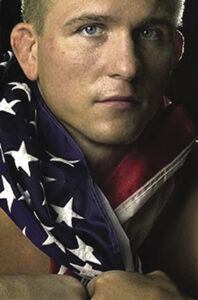

By Billy Liggett | Photos by Jordyn Gum

In a 10-year span from 1990 to 2000, Cary Kolat went from being the biggest name in American wrestling to the most cursed.

A 1992 feature on a then 18-year-old Kolat in Sports Illustrated deemed him “The Best There Ever Was” after he tore through Pennsylvania high school wrestling with a perfect 137-0 record. He won two national titles for Lock Haven University after going a combined 50-1 in 1996-97 and won silver and bronze medals at the 1997 and 1998 world championships in Russia and Iran and three gold medals in the World Cup from ’98 to 2000.

But Kolat’s goal from the beginning — from the moment he first strapped on his Dan Gable wrestling shoes as a 7-year-old kid — was an Olympic gold medal. That dream died in his first match in Sydney, Australia in 2000, after his victory was protested and overturned, and Kolat lost the subsequent rematch. It was the third time in four years that one of his wins in a world-level championship was stripped by a protest from his opponent.

The string of bad luck led U.S. coach Bruce Barnett to tell reporters in Sydney, “When I get to Heaven, one of the first things I’m going to ask is: Why does this keep happening to Cary Kolat?”

Kolat finished ninth in his only Olympics at the age of 27.

But while it may have felt like it at the time, his journey didn’t end in Australia. After leaving wrestling entirely to try his hand at event marketing and public relations, Kolat returned to the sport as a coach and eventually landed at the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill in 2010 as the school’s associate head coach.

Today, he is the head coach of Campbell University’s wrestling program, a program that reminds him a lot of his days at Lock Haven, a small, rural school where wrestling tops football and basketball as the “high profile sport.” He’s been tasked with turning around a program currently serving a one-year postseason suspension due to low Academic Progress Rate of its student-athletes.

Sitting in his still mostly bare office a few steps from a Gore Arena he says is much nicer than his facilities back at Lock Haven, Kolat is both relaxed and confident about his program’s future and seemingly content about his accomplishments and where his roller coaster of a career has landed him.

“When I left wrestling, I learned a lot about myself,” says Kolat. “And now, I’m exactly where I want to be at Campbell. The smaller setting is more comfortable to me. I can get the same results here that others get at a larger school. I understand the type of kid who wants to come a program like this and compete at a high level. Some might see barriers here. I see a great challenge.”

“The people of Greene County, deep in the coal country of southwest Pennsylvania, have seen it all — times when a man could work double shifts every day until his strength gave out, and times when the mines closed down and it was a struggle to find any work at all. But they have never seen a wrestler like Cary Kolat.”

— Merrell Moden, Sports Illustrated, April 16, 1992

A perfect 137-0. And very few of those matches were even competitive.

When he was a freshman at Jefferson-Morgan High School in Jefferson, Pennsylvania, his teammates called him “Son of Gable,” after Kolat’s hero, the 1972 Olympic gold medalist and first and only amateur wrestler to ever grace the cover of Sports Illustrated.

Four times, he was named Outstanding Wrestler at the state finals (no other Pennsylvania wrestler had ever won it twice); and in his 137 matches, Kolat was only reversed (when a wrestler comes out from below his opponent and gains control) five times and not once ever had his back exposed to the mat.

Kolat lived up to his “Son of Gable” moniker when Sports Illustrated writer Merrell Moden traveled to southwestern Pennsylvania to write about the sport’s next big thing. Moden’s feature told of a Saturday night in January when 2,000 people packed a small high school gym in Trinity “to get a look at this prodigy.” Trinity’s coach opted to forfeit against Kolat, and he was booed by his home crowd for the decision.

The magazine article went into great detail about Kolat’s childhood, which consisted of constant training and wrestling meets. One year, Kolat and his parents spent 32 weekends in motels. The article also suggested the regimen wore on young Cary, whose father asked him to purposely fail the eighth grade so he could have another year of maturation before high school. When he was a sophomore, he once told a newspaper (when asked about his advice to younger wrestlers) to have fun with it and don’t make it a job. “If it becomes too much like a job, get out of it,” he said. “It’s like a job to me, but I plan on making my living out of my wrestling.”

When asked today about what being featured in Sports Illustrated does to an 18-year-old kid ready to make the leap to college, Kolat leans back in his chair, looks up and laughs.

“My wife makes fun of me when she finds old articles or TV interviews,” he says. “You think you know everything at that age. All the attention and I got or any so-called ‘celebrity’ around me, I didn’t notice it back then. My parents were good about keeping me humble, and I think I handled it as well as anyone.”

He chose Penn State straight out of high school, and after a prep career, Kolat suffered his first collegiate loss two weeks into his first season. The setback was a much-needed wake-up call. Kolat says it taught him how to deal with defeat and adversity. “You’re only beaten when you give up,” he says.

He went 22-5 overall his freshman year, falling in the NCAA title bout to a UNC-Chapel Hill wrestler. His sophomore year in 1994, he was named Big Ten Wrestler of the Year and ended his season 39-1, his loss coming in the NCAA semifinals. He was an All-American both years. He also wrestled against a University of Iowa team coached by none other than his hero, Dan Gable.

Kolat transferred to Lock Haven for his junior year after a disagreement with his coach at Penn State — Kolat wanted to redshirt for a year to focus on international style wrestling, to which his coach objected. At Lock Haven, he won his first national championship in 1996 and his second the following year, finishing his two years with a record of 50-1. He ended his college wrestling career with an impressive .941 winning percentage (111-7) and 53 career falls.

Everything up to that point, however, was merely preparation for the Olympics in Kolat’s mind. In 2000, Kolat and the U.S. Wrestling Team competed in Sydney — and the 138-pound star faced defending world champion Mohammad Talaei of Iran in the first round. Kolat defeated Talaei, 3-1 in overtime, but Talaei protested a two-point scoring move Kolat initiated off a scramble.

The Iranian won the protest, and he defeated Kolat 5-4 in the rematch. The loss made Kolat’s road to gold nearly impossible, and he finished his only Olympics competition ninth overall. Devastated, Kolat didn’t speak to the media after his loss.

Fourteen years later, he’s still disappointed. But there’s a level of acceptance and “moving on” in his words when talking about it today.

“I struggled with it for a long time,” he says. “People would come up to me and ask me about being an Olympian and ask about how great the experience was, but at the time, anything less than a gold medal was devastating. If I can redo things, I would have soaked up the experience more. At the time, the Opening Ceremony was just getting in the way of my focus on the event. I was so focused, I didn’t enjoy any of it.”

There was one part he remembers fondly.

“My wife [Erin] and I did find out we were pregnant there,” he says, smiling. “So it wasn’t all bad.”

“Actually, I’ll be happy when I can do a regular job or something, whether I use my degree or not. I see people working in grocery stores and stuff, and they don’t realize, I envy them. I’ve never had a part-time job. My wife says, ‘Oh, yeah, I worked at a store in the mall.’ I think that would have been so fun.”

— Cary Kolat, Pittsburgh Post-Gazette, Sept. 10, 2000

With Sydney behind him, his first child on the way and the rest of his life uncertain career-wise, Kolat defaulted to what he knew best. He became a wrestling coach at Lock Haven in 2001. He moved to North Carolina in 2003 to join the coaching staff at UNC.

With Sydney behind him, his first child on the way and the rest of his life uncertain career-wise, Kolat defaulted to what he knew best. He became a wrestling coach at Lock Haven in 2001. He moved to North Carolina in 2003 to join the coaching staff at UNC.

While in Chapel Hill, Kolat looked to expand his horizons. He began working part time for Newell Rubbermaid, and in 2005 the company announced Kolat would spearhead a grassroots marketing effort for Sharpie and Papermate products, managing advertising and event marketing to target fans of youth, high school and college wrestling. He also worked several NASCAR events, attending 22 races one year (a lot for a guy who was never a racing fan to begin with).

While he was still involved in wrestling and athletics, Kolat embraced his new role as a PR guy, which allowed him to develop his skills speaking in public and meeting new people.

“When you’re young and a competitor, you don’t really want to deal with people at times,” he says. “You just want to run through them. My few years in marketing helped me a lot — it shaped me for this job as much as anything else I did before this.”

In 2008, Kolat put his PR skills to good use and launched kolat.com, a popular wrestling site full of videos and articles on wrestling techniques and a site Amateur Wrestling News recently dubbed “the library of congress of wrestling.” He returned to UNC in 2010 and became the associate head coach (and the “head coach in waiting” some believed). When he saw the opening at Campbell in 2013, he was intrigued, having visited the campus before and seeing the facilities.

Campbell reminded Kolat a lot of Lock Haven. And this was a very good thing.

“I know what it’s like to be at a small school,” he says. “I believe Campbell can develop a pretty good niche. I like where we’re located — the eastern region of the U.S. is catching up with the North and getting much better. A lot of those kids are heading south for the weather, and the programs are finally attracting them.”

He also liked what Campbell offered academically. Despite the APR setback, Kolat saw a school where academics came first.

“I’m looking for guys who want to succeed in everything they do, and that starts in the classroom,” he says. “If their teammate gets a 95, he wants a 96 or a perfect score. If his teammate is playing frisbee football, he wants to beat him at that, too. College is such a grind mentally that if you’re just here to wrestle and you don’t have that balance, you’ll struggle and you just won’t smile as much. Struggle academically, and you can’t train the way you want to train.”

Wrestling workouts began in October, and days into the new season, Kolat’s student-athletes were already sold on Kolat’s vision for the program.

“Our first impression of him wasn’t intimidation, but rather here’s a hard-nosed guy who’s ready to get started,” says Drew Walker, 20, who is teammates with his twin brother, Tyler. “The first time we met him was the first practice, in the locker room, and he gave us this big speech. He was excited, and we got excited as well.”

“I was excited when I heard he was coming,” says Tyler, adding that he and Drew knew a lot about Kolat growing up in Pittsburgh. “I’ve read about him, watched videos of him. My high school coach was even coached by him.”

Freshman Luke Stewart of Lynchburg, Virginia, says Kolat made an impact on him on Day 1. A talented wrestler who admits his flaw is giving up too easily when things get tough, Stewart says he’s getting mentally and physically stronger each day in the program.

“In high school, I always said to myself I’d go to a program coached by the best, and one day I’d become an All-American,” Stewart says. “I think that can happen at Campbell. When I first met him, I knew he wasn’t playing any games. He wants champions here. That’s all there is to it.”

Kolat says the program will crawl before it can run. His late hiring put the program behind the eight ball in terms of recruiting, and also contributed to a lighter schedule that will include no post-season.

“We’re rebuilding,” he says. “But I see us improving this year and having a great team in 2015-16. Campbell’s never had an All-American before. We’re going to change that.”