A Modest Monument

With few trees to block the biting cold wind on a sunny December afternoon, Dr. Christopher Stewart looked down at the modest brick monument dedicated to the wife of Campbell University’s founder and, face to the wind, thought out loud about the importance of the spot where he stood.

“I wish someone would have a plaque here about what this house meant to the community … to Campbell University,” said Stewart, looking at what’s now an empty field of grass near the entrance of the Keith Hills community. “There was just so much history in this house.”

“This house” was the birthplace of Cornelia Pearson, who would become Cornelia Campbell, wife of University founder Dr. James Campbell. It later became the Matthews Home, owned by Neil Matthews, father of 13 and the great grandfather of Stewart, an internal medicine physician who in 2010 became the first medical director of Campbell’s new Physician Assistant program.

But that title is far from the only connection Stewart has with Campbell University. His roots go all the way back to the school’s founding 125 years ago … and beyond.

It was Neil who helped build the Baptist church that still stands today on the Campbell campus, and it was Neil’s house — the one he rented from the Campbells and that once stood within eye-shot of Campbell’s home — that served as a meeting place where several discussions about the future of the school were held.

Great aunts and uncles attended, taught and supported Campbell as it grew from Buies Creek Academy to Campbell Junior College to Campbell College.

Stewart’s parents attended Campbell and met there. And today, Stewart is part of a program that’s helping launch the school toward a future as a state leader in health care education.

For every milestone at Campbell University over the past 125 years, a Stewart or a Matthews has been on hand to witness it. It’s a fact that’s not lost on Christopher Stewart, who grew up in Buies Creek but attended the University of North Carolina partly to see what else was out there.

Since he’s returned, he’s grown to appreciate his family’s place in Campbell’s history a little more.

“I realize that my family was here during the founding — and played a role in it — and here I am today the founding medical director of the P.A. program,” Stewart said as he escaped the wind and cold and climbed in his Jeep. “I think about it sometimes — the full-circle component of all of this — and it’s really unbelievable to me.

“I’m incredibly blessed to be here.”

No Dancing at Campbell

When I was in school, dancing was strictly forbidden.

When I was in school, dancing was strictly forbidden.

Once, when I was a sophomore in high school, some friends and I who were on the basketball teams went to a friend’s house one Saturday night for a party to celebrate our good season. We played records and were sort of playing around — it wasn’t really dancing.

The basketball coach observed what we were doing, but said nothing to us. The next night, the coach walked home after church with my father and told him we were “dancing” at the party.

On Monday morning, we were called in by my father and were severely reprimanded for having violated the rules. We thought the coach should have told us at the party that he thought we were breaking the rules.

— Catherine Campbell King,

granddaughter of J.A. Campbell,

daughter of Leslie Campbell

Rooted in Campbell

“Papa never kept up with the names of his children too well. When Papa wished to address the youngest, he would start the roll call. When his breath ran out, he would exclaim, ‘Hey, You.’ The family combined the words and gave the last of the mob the name, ‘Hugh.'”

— Excerpt from ‘Neil’s Way,’ by Hugh A. Matthews, M.D.

Neil’s Way

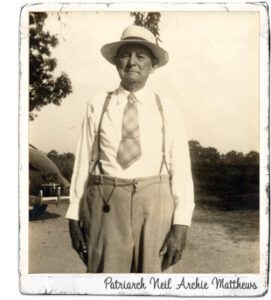

in 1978, Hugh Matthews — who one year later would be named a Distinguished Alumnus by Campbell University — published “Neil’s Way,” a book about growing up the youngest of 13 children born to Annie Jane Stewart and Neil Archie Matthews.

Much of the book takes place in the Matthews home (called the “Big House” or the “Pearson Place”), which is also depicted on the book’s cover. Neil Matthews rented the house and the 200-acre farm that came with it from Cornelia Pearson Campbell, also known as “Miss Neelie,” for one 500-pound bale of cotton per year in 1909.

But if there’s a point where Stewart’s family tree begins to weave through the timeline of Campbell University, it is about 25 years earlier — before that first class at Buies Creek Academy in 1887 — when Neil Matthews befriended Dr. Campbell, described as “red-haired, tall and immaculately dressed” in the book.

The First Campbell Car

You might recognize the name of the first man who owned a car at Campbell University. There’s a lecture hall and scholarship named after him to this day.

Blanton A. Hartness, class of 1928, introduced the automobile to Buies Creek in 1927. It was the same year Ford Motor Company introduced its popular Model A, the successor to the Model T.

Hartness would go on to have quite a career in North Carolina. He owned Sanford Milling Company Inc. and eventually Vanco Mill in Henderson. His family produced the popular Snowflake and Hartness Choice flour brands used in kitchens throughout Eastern North Carolina for years. The company is still going strong today.

Hartness’ name graces a lecture hall in the Science Building and a scholarship awarded annually to a full-time student in the CPHS.

The two men were polar opposites in almost every way, according to Stewart.

Campbell was the stoic leader, a man who “wherever he sat, he was the head of the table,” according to another book on the school’s history, “Big Miracle at Little Buies Creek,” by the late Dr. J. Winston Pearce. Matthews, on the other hand, was rugged and uneducated … a man who was more comfortable in the cotton fields than in a room full of people.

Campbell was a dynamic preacher and pastor who led several churches in Harnett and Sampson counties. Matthews, too, was a man of God, but a man more known for language that would make a sailor blush … a man, Stewart said, who once asked Campbell to walk ahead of him so he alone could get a buggy unstuck from a muddy creek bed. The story goes — a story passed through generations of Stewart’s family — Campbell walked up a hill, and a few minutes later, saw Matthews walking behind him with the buggy successfully freed from the mud.

“Neil just cussed it out of the creek,” Stewart said with a grin. “I guess he just didn’t want Dr. Campbell standing there.”

Despite their differences, the friendship worked. And having Matthews by his side proved to be beneficial to Campbell University’s founder.

According to the Harnett County history books, Matthews’ team of mules played a considerable role in hauling bricks for the construction of Buies Creek First Baptist Church, which left the one-room wooden building it had occupied when Campbell joined to move to its current location across from the campus building that bears his name.

Stewart said as their friendship grew, Matthews became somewhat of a right-hand man for the doc.

“I was told that if Dr. Campbell needed anything done in the community for the school, he went to Mr. Neil,” Stewart said. “I have heard of several instances where Neil came to Dr. Campbell’s defense for important issues at the time.”

Stewart said Matthews’ mules also helped haul the bricks and supplies for the Kivett Building, Campbell’s signature structure constructed in 1903 after a fire destroyed the previous main building a few years earlier over Christmas break.

Six years later, when Matthews moved his family to the “Big House,” the two families’ homes were separated by a pasture and what is now U.S. Highway 421. Campbell would visit the Matthews regularly, Stewart said, and would talk on end about the school’s future.

“A lot of what made Campbell Campbell happened there,” he said.

By 1926, Buies Creek Academy had grown to become Campbell Junior College. Eight years later, Dr. Campbell died months after suffering a heart attack. Matthews died almost exactly 11 years later from a stroke.

“My great-grandfather … he and Dr. Campbell were the best of friends,” Stewart said. “My family has passed down so many good stories about the two … I wish I had written them all down. I remember a story of the time Dr. Campbell asked Neil just how many kids he had, because, you know, he had so many.”

“‘Dang if I know,’ my great-grandfather said. ‘I haven’t been home yet today to count ‘em.’”

“My mother tells me that the Neil Archie Matthews family was the most loving, caring people she has ever known. All 12 children had brilliant minds; all the men were tall and handsome; all the ladies tall and beautiful …”

— William Brooks Matthews, cousin of Christopher Stewart, great-grandson of Neil Matthews

Generations of Matthews

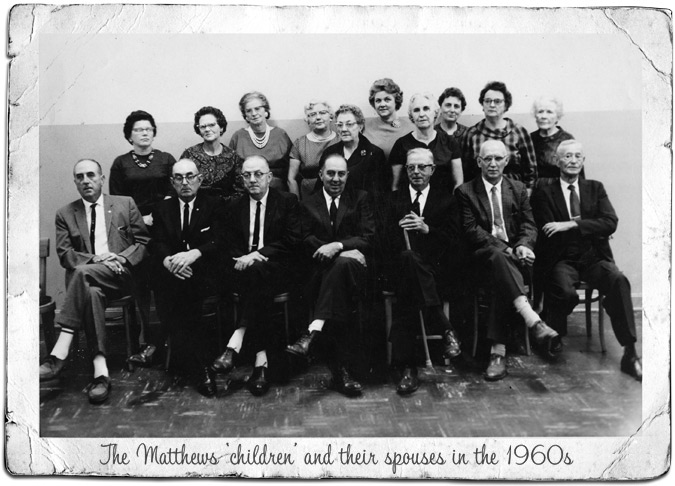

Between 1892 and 1914, Annie Jane Stewart Matthews and Neil Archie Matthews had 13 children (the second-to-last child, Ruth, died at birth in 1913).

The couple saw four of their boys march off to war — three in World War I and one in World War II — and one son, Kenneth Clifford, would be listed as “missing in action” before returning home, though for years would suffer the effects of mustard gas and shell shock.

They would go on to become nurses, deputies, barbers, teachers, business owners, homemakers, doctors, authors, and like their father, farmers.

“They were absolutely wonderful people,” Stewart said. “Real-life characters … salt of the earth.”

Of the 12, nearly all of them contributed to the growth of that school in Buies Creek, whether as students, employees or supporters.

There was Milton, the fourth child, who followed in Neil’s footsteps as a farmer and took over his father’s operation at the “Big House” in 1939 before eventually selling to Campbell University. That 200-acre farm would later become Keith Hills, home to a beautiful community, country club, golf course and soon, North Carolina’s first new medical school in 35 years.

Palmer, the seventh, fought in World War I and returned for a career of farming and selling vacuum cleaners. He entered Campbell lore, however, close to his retirement when he started Pop’s Grill, which catered to college students and Campbell faculty and staff.

“It became a student hangout,” Stewart said. “And ‘Pop’ was quite a character … I remember him really well.”

A vocal Campbell supporter, ‘Pop’ would regularly attend baseball games and bang on metal trash cans when the other team was up to bat, according to Stewart.

“The person who told me this said it was so loud, you could hardly bear it,” he said. “The Campbell players loved it, of course, and it rattled the other team terribly.”

Gretchen, No. 8, went by the name “Dutch,” and for years, he served as director of the Physical Plant at Campbell. He later built and operated a country store and service station by his home, another business frequented by Campbell students and faculty. He, too, was a big supporter of the local school, Stewart said.

“When the late professor Dr. A.R. Burkot (of whom Burkot Hall is named) first moved to Buies Creek, he couldn’t borrow enough money to buy a house and settle here,” Stewart said. “Uncle Dutch loaned him the money to buy a house, and Burkot would say many times that Dutch was one of the reasons he was able to come to Campbell. He was forever grateful.”

Ora excelled as a student at Buies Creek Academy and went on to become a nurse. She married a doctor and the two started a practice out west in Canton, N.C. Margaret was a teacher and eventually the cafeteria manager at Angier High School for many years.

The youngest of the 12 — and perhaps the most successful — was Hugh Archie Matthews, the author, Distinguished Alumnus, artist and physician.

Hugh studied at Campbell, Wake Forest, Duke, Yale, UNC, Johns Hopkins and Iowa State, earning a degree in biology, a master’s in English and an M.D.

In his 30s, he volunteered for service during World War II and was wounded while working as a physician in a field hospital in Italy.

He would go on to start a practice in Canton, where a few of his siblings lived, and became an adjunct professor at West Carolina University. He served on the Governor’s Commissions on Cancer and was a member of Campbell’s Board of Trustees and the General Board of the Baptist State Convention. He was also founder and president of the North Carolina Health and Safety Council.

The Matthews children had 29 children of their own combined, five of whom fought in World War II. And many of them — including Stewart’s father, attended Campbell College. Stewart said he has so many cousins in and around the area, he probably hasn’t met them all.

“My great-grandmother, until the day she died, sat with one leg out, because her entire life, she always had a kid or a grandkid sitting on her lap,” Stewart said.

“There are certainly a lot of us.”

“You may travel the country over, from ocean to ocean and border to border, and almost everywhere, you will find that Smith and Jones outnumber all others. Here in Buies Creek, the name is Stewart. And pity the newcomer who makes an effort to learn the relationship of our many citizens who bear this Scottish name. … The best advice to an outsider is that he refrain from speaking evil of anyone of the name, for the hearer may be a cousin.”

— Dr. A.R. Burkot, Late Campbell professor, “The House of Stewart – Buie’s Creek Clan”

Keeping Up With the Stewarts

Burkot attributes the vast number of Stewarts in the area to family patriarch David Stewart, who “added to the confusion,” Burkot wrote, by marrying three times. “The resulting accumulation of half-brothers and half-sisters,” according to Burkot, “would challenge an expert in building family trees.”

Neil Matthews’ wife, Annie Jane, was a Stewart. But the “Stewart” in Christopher Stewart was the result of Wade Stewart, his grandfather, who married Neil’s daughter Annie in 1931. Annie was a homemaker and Wade the sheriff of Harnett County.

Like Neil, Wade’s father Tom Stewart was

a friend of Campbell University founder Dr. J.A. Campbell. According to Christopher, Tom Stewart and his brother would accompany Dr. Campbell on trips to churches around the state to help raise money for the school.

In essence, they were among Campbell’s first advancement team.

“Where the Matthews were this large farming family who mostly contributed to Campbell from the outside, the Stewarts helped Campbell grow from the inside,” Christopher Stewart said. “I don’t want it to sound like they were superior in any way … but they certainly had more education, at least early on.”

Perhaps the Stewart with the biggest impact on Campbell is Dorothea Stewart Gilbert, who at 85 still runs the Lundy-Fetterman Museum and Exhibit Hall. Known as “Dot” in the family, Dorothea attended grades 2 through 7 in the 1930s in the Kivett Building at Campbell, and then high school in the D. Rich Building, which stands just a few feet away.

She graduated from Campbell Junior College in 1946 before earning a bachelor’s degree in English at Western Carolina. Her teaching career began two years later at Buies Creek High School, making $150 a month teaching English, French, world history and first aid; coaching basketball and football; directing two plays a year; and planning all graduating activities.

Christopher Stewart’s parents, Larry Stewart and Gale Byrd, met at Campbell in the 1960s

She became an instructor at Campbell Junior College in the 1960s and would go on to teach for 32 years. In 1986, the Pine Burr dedicated its yearbook to her and included a quote from Campbell’s third president, Dr. Norman A. Wiggins:

“A true teacher is one who not only teaches her students to do the right thing, but to enjoy doing the right thing. Professor Dorothea Stewart is devoting her life to being a true teacher.”

Another Campbell mainstay was Christopher’s great aunt Juanita Stewart Hight, who graduated from Campbell Junior College and eventually became director of public relations for the school and would serve on the Board of Advisors. The Hight House, which currently sits across from the building housing Campbell’s new Physician Assistant program, was named for her, according to Stewart.

Kirkland Stewart was Campbell’s constable and night watchman for many years. Gene Stewart served as Campbell’s chief of security, housing director, dean of men and assistant dean of students during his career.

Rudolph Stewart, Christopher’s uncle, attended Campbell Junior College and went on to architect school in Virginia before enjoying a long career with NASA and Boeing. One of his drawings of Charles Schultz’s “Snoopy” is currently on display in one of NASA’s space museums as it went up with the astronauts during one of the early space missions.

Not all the Stewarts were stalwarts of the school. According to Christhopher Stewart, “Uncle John” was to Buies Creek what Otis was to Mayberry … Campbell administration in the 40s and 50s would find reasons to lock him up so he wouldn’t harass the women at the Baptist Student Union or the young girls in town for Homecoming festivities.

Larry Hinton Stewart attended Campbell College (it dropped the “Junior” in 1961) from ‘60-’63. At one point, he worked in Carter Gym handing out sports equipment, though his job mostly consisted of watching TV, napping and playing cards with the students.

“The worst money Campbell ever spent,” his son, Christopher Stewart, joked.

His Place in History

Gayle Byrd was one of three sisters to attend Campbell, going from ‘64-’67. It was there she met Larry, and in 1972, Christopher was born.

Growing up in Buies Creek, young Chris couldn’t help but be involved with Campbell at a young age.

“So much of what happens in Buies Creek is Campbell related,” he said. “Everything just blended — the community and the university — into this one working machine.”

His earliest memories were the sports camps he attended — basketball, soccer, baseball — and to him and his friends, Campbell meant fun and sports.

“We used to play on the campus all the time,” he recalled. “That was our playground when we were kids.”

And he couldn’t escape Campbell at home either. He recalled the day the basketball coach came over for a visit and began talking optimistically about a new gymnasium.

“He said, ‘I think we’re going to finally get that new gym this year,’” Stewart said. “Of course, that didn’t happen for another 30 years, but I’ll always remember that visit.”

Very little, Stewart said, did change at Campbell during his childhood and into his early adulthood. Sure, during the 80s, Campbell did establish a School of Business, a School of Education and a School of Pharmacy, but the look of the campus remained much the same, he said.

When it came time for him to think about higher education in the late 80s, Stewart chose Chapel Hill over Buies Creek.

“I felt the need to get away and experience life somewhere outside of Harnett County,” he said. “Don’t get me wrong, Buies Creek is a wonderful place to grow up and raise a family. But when you’ve spent your entire life there, you get to thinking about what there is to do elsewhere.”

After four years at UNC, he went to medical school at East Carolina University and then began his internal medicine residency in Charleston, S.C.

In 2002, Dr. Linda Robinson asked Stewart to join her practice in Coats, located a stone’s throw from where he grew up. He agreed, though even then, he had no intention of ever becoming involved in the university so many in his family had been a part of.

“Campbell was the farthest thing from my mind at the time,” he said. “To me, in 2002, it looked the same it did back in ‘72.

It wouldn’t take long for that to change.

One year later, Campbell’s fourth president, Dr. Jerry Wallace, was elected. Three years later, Campbell opened its doors to a new College of Pharmacy building. The following year, construction on the John W. Pope, Jr. Convocation Center — now a signature facility — began.

Most importantly for Stewart, that same year in 2008, the Board of Trustees approved a master’s program in Physician Assistant studies.

And in 2010, he was asked to be the medical director.

“For things to fall in line the way they have, you couldn’t play it out any better,” Stewart said.

Today, Stewart’s list of responsibilities at Campbell is impressive. In addition to his involvement in the P.A. program, he has been appointed to the faculty for the School of Osteopathic Medicine, which is expected to open its doors in the fall of 2013 … on the same land his great-grandfather once farmed.

He’s also director of Student Health Services and medical director for the Athletic Training program at Campbell.

Not bad for the descendant of an over-cussing farmer.

“He would probably not know what to think,” Stewart said when asked what his great-grandfather would think of Campbell today. “He’d be shocked just like I was when I looked around and saw what was happening at this campus.”

Stewart said he owes a lot to Campbell University and the generations of Stewarts and Matthews who preceded him. He’s also thankful for his friends growing up, many of whom were the sons of daughters of Campbell University professors and staff.

“The biggest impact Campbell had on my life was bringing in such interesting and fantastic people to tiny little Buies Creek … people who would otherwise never come here,” he said.

“I can say with confidence if I hadn’t had those kids — who remain best friends to this day — in class with me, I wouldn’t be where I am today. They made me better, because they came from families that valued education and encouraged their kids to do the same.

“That is probably the greatest gift Campbell will ever give me.”

Thanks For The Memories

Dr. Christopher Stewart would like to thank the following friends and relatives for sharing their memories to help tell his story: Carol Leggett, Gene Stewart, Dorothea Gilbert, Dr. Bobby Roberson, Dr. Bruce Blackmon, Dr. Burgess Marshbanks, Brooks Matthews, Tom Lanier and Buddy Brown.

Where is Tara?

Having grown up in the Phillipines and having my views of the American South shaped by movies such as “Gone with the Wind,” I was quite surprised when President Leslie Campbell, who met me at a bus station in Raleigh, brought me to Buies Creek in 1955.

I saw almost nothing but tobacco barns and small houses — there were no Taras anywhere.

— Leonore Doromal Tuck

from Campbell archives

The Last of the Big Four

Shortly following the funeral of Fred McCall, I was crossing the campus with a colleague, and casually mentioned that “the last of the big four had just passed away”.

He asked, “Who were the big four?”

I replied, “Dr. Leslie Campbell, Dean A.R. Burkot, Lonnie Small and Fred McCall.”

It should be known that Fred McCall is a Hall of Fame basketball coach. His close associates knew him as “Juice,” but I always called him “coach.”

It is not well known that Fred and Bones McKinney founded the very first basketball school in the country right here in the cracker box known as Carter Gymnasium.

The Campbell basketball school brought to this obscure little campus such names as John Wooden, Dolph Shayes, Press Maravich, “Pistol” Pete Maravich, Dean Smith, Michael Jordan … just to mention a very few of the greatest names in basketball .

— Dr. James M. Jung

Campbell’s First Computer

The story of how Campbell obtained its first desktop computer began in a department chairmen’s meeting in the spring of 1981. At the conclusion of the meeting, then President Norman Wiggins announced that he had available some grant money to be used by faculty to attend summer workshops.

He suggested that we might learn something about these new “mini computers.” He meant “micro computers.”

I applied for one of the grants, but for the purpose of “Learning of Recent Developments in Organic Laboratory Techniques.”

In the fall of 1981, two years before IBM came out with its PC, the Department of Chemistry acquired its first TRS-80 Model III with two disk drives and the LP-VIII line printer.

The computer and printer was set up in Room 306 of the science building, and I issued keys to several faculty members so they, too, could come work on that computer. Dr. Jerry Taylor, who later taught computer courses in the math department and Dan Ensley, who later became head of the mass communications department, were two who benefited from that TRS-80.

Interestingly, Dr. Max Peterson of our own Chemistry department, was doing some moonlighting at N.C. State. At that time, NCSU’s chemistry department did not have computers, but once they became aware of what Max had done on our TRS-80, N.C. State acquired computers the following year.

When IBM’s PCs took over a few years later, that TRS-80 was still functioning, even though the paint on the keyboard had been worn completely away.

— Dr. James M. Jung

from Campbell archives

World War II & Campbell

Veterans were students — that made them unique. I think the returning veterans of World War II had a good effect. They were more mature and didn’t think throwing trash cans down the hall and other such pranks were funny.

— Bruce Blackmon, Class of 1940

During World War II, German prisoners of war worked in this area. I think they worked on the Campbell farm and helped lay the floor of Layton Hall when it was rebuilt after the fire.

They stayed about a year after the war was over. The Germans, unlike the Italians, who were here in North Carolina, too, adapted well to the area.

I think it was Dutch Matthews who would bring the German prisoners a Pepsi and a Honey Bun in the afternoon when it was hot.

— Robert King, Class of 1949

While WWII served to increase the female enrollment, because of the demand for secretaries and clerks, it almost wiped out the male student body. By the end of 1942, there were only 25 of the male members of the student body left. The others had been drafted or had volunteered.

The men who remained at Campbell during WWII were given training, too, just in case they were drafted or faced invasion. The women underwent the same physical training.

There were obstacle courses to run, and men who came back after their military service said Campbell’s obstacle courses were as hard as any they had seen in the Army. I can remember swinging on ropes and scaling fences … and slipping and falling once, too.

— Diamond Matthews, Class of 1943

I can remember during WWII students here were drilled for enemy invasion. The coach (his initials were S.O.B.) had an obstacle course, and honest-to-Pete, it was just as rigorous as any I experienced in the Army.

— Robert King, Class of 1949

After WWII was over, the veterans helped Campbell develop a winning football team. They also played an important part in liberalizing some of the rules. For example, the veterans were in the vanguard of those who wanted to have dances on campus. Gradually, official opposition was overcome. First, square dances were held in the Old Gym. Later, other types of dancing were admitted — a real triumph.

— Diamond Matthews, Class of 1943