It’s like walking across a tight water bed. A tight, acre-sized water bed. Only here, the two-inch-thick plastic beneath your feet is all that separates you from a lagoon filled with 6 million gallons of pig waste.

But that waste is why we’re here. It’s why National Geographic has been here. Rolling Stone Magazine and the Sierra Club. U.S. senators, governors and dozens of elected officials. Even an American Idol runner-up.

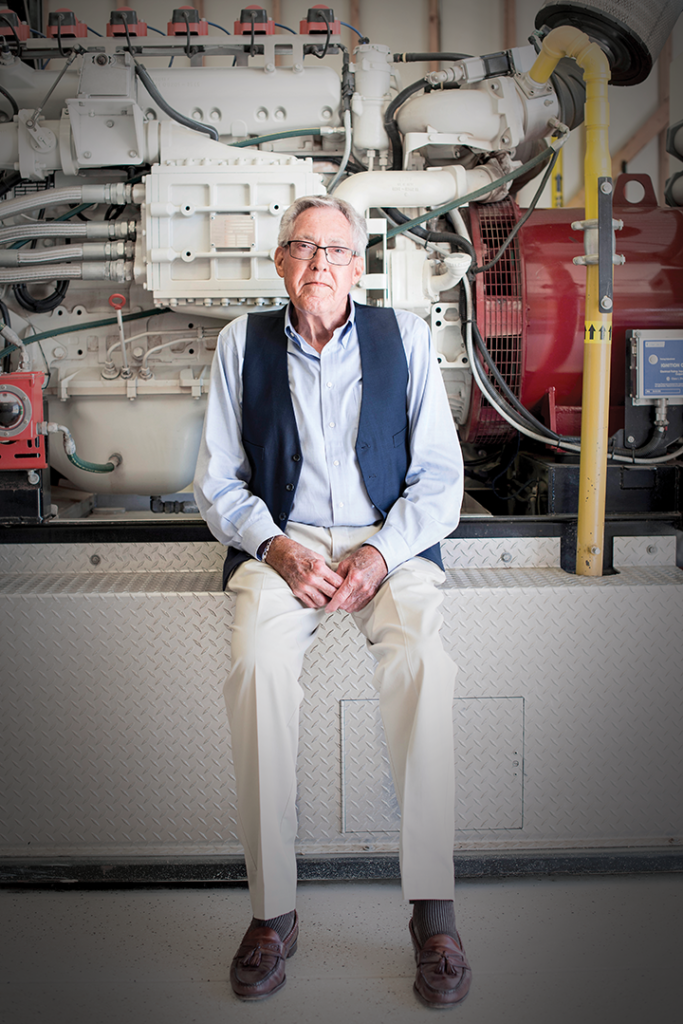

Tom Butler takes great pride in the power of his pig poop.

More specifically, the 77-year-old Lillington native and lifelong farmer takes pride in that poop’s potential. His covered lagoons are trapping methane gas, which in turn is powering his farm and will soon provide energy to its own grid of homes in Harnett County. Those giant green plastic tarps are also keeping the smells at bay — much to the appreciation of his neighbors in the rural, southwestern portion of the county — and plans are in the works to recycle the leftover sludge and produce nitrogen-based fertilizer.

Last November, Butler received Campbell University’s first Rural Health Advocacy Award for his innovations and his efforts. Introduced during the awards ceremony in the Alumni Room at Marshbanks Hall as the “high-tech redneck,” Butler was a man of few words behind the podium as he held the 13-inch glass award that now sits on a filing cabinet in his small shack/office just steps away from the much larger pig houses on his farm. But those few words were hopeful.

“We are hoping to build an organization that is industry-changing to rural areas,” Butler said before thanking the crowd and returning to his seat.

Six months later, in front of a much, much smaller crowd (a few writers and a photographer), he’s more comfortable accepting the accolades. But, of course, that’s not why he’s doing it.

“I just want to do the right thing,” he says. “If we don’t do the right thing — as an industry — people are going to suffer. I’d rather do the right thing than profit while people suffer.”

THE PHONE CALL

Like most Harnett County farmboys in his day, Butler grew up with tobacco.

He also grew up with Campbell — in the 50s and 60s still a junior college where several cousins, aunts, uncles and others in his family attended. Butler was also a Campbell student for a short time, though out of necessity more than choice. His high school algebra teacher died before his senior year, and he was forced to take it at Campbell to earn credits to attend the closest four-year school, East Carolina University.

Butler and his brother inherited their father’s 130-acre farm, but bailed from the tobacco industry in the early 90s to become contract hog farmers. The Butlers built six hog houses (they would add four more a year later), and their first pigs arrived on June 25, 1995.

“I joke that for the first part of my life, we killed people with nicotine, and for the second part, we’re killing people with pathogens, odors and polluted groundwater,” Butler says, though his tone is far from joke-like. “And we really are, as an industry. The only difference was with tobacco, we did it voluntarily.”

Not long after those first pigs arrived, Butler was introduced to the smell. THE smell. He recalled to National Geographic the first time he ever flushed the waste from his hog house: “I pulled that plug, and I smelled that smell, and I wondered, ‘What have I gotten myself into?’”

The stench hit him hard, but the desire to do something about it didn’t hit him until a few months later. A phone call came one night from his brother’s wife’s sister, who lived within two miles of the farm, informing Butler that “we can smell the s— in my house.”

“This was serious,” Butler says. “This really concerned me. We don’t have the right to make anyone suffer while we profit. If we can do something to lessen the impact on our neighbors, then we should be doing something.”

The first step was covering the lagoons. Butler Farms produces 10,000 gallons of waste a day — the floors of the hog houses are elevated, and the waste from the pens falls through inch-wide slits throughout the the building. That waste is then flushed into the nearby lagoons and on many hog farms in North Carolina, treated with chemicals. Left alone on a ripe, hot summer day, the odor from these lagoons is nauseating. Headache- and vomit-inducing.

The tarps — a high-density plastic that keeps everything in the lagoon — worked immediately for Butler. There’s still an odor on the farm, most of it emanating from the buildings. But even standing on those green tarps — your feet wobbling beneath you — the smell is tolerable. At times, when the wind is light or blowing away, the odor is gone completely.

Another benefit: the tarps keep out millions of gallons of rainwater, preventing it from mixing with the waste and creating millions of gallons of wastewater. Butler is also a vocal opponent of the widely used practice of spraying crops with lagoon water, which he called a “black eye for the industry” in a recent IndyWeek article because of the respiratory and health problems the mist can cause for those who live nearby.

And finally, the smell isn’t the the only thing trapped under the tarps. Pig waste, like most forms of animal waste, releases methane as it decays. Butler’s farm emits 6,000 tons of carbon dioxide and methane each year, potential energy that was going unused.

Butler has invested more than $1 million into a giant yacht motor, pipes and other technology to capture that methane and convert it into energy. That motor — twice as tall as Butler and about 10 feet long, housed in a small shed behind his hog houses — is powered by a small row of nearby solar panels, making his farm more than just energy self-sufficient. In fact, he’s producing enough energy to put about $8,000 to $10,000 worth monthly back into the grid.

“Everything we’ve done in the past eight years — the research, the development and the work — that’s been expensive,” Butler says, standing next to the motor that he’s visibly proud of. “Putting energy back into the grid will help pay for it and will help us continue to do more research and find better ways to improve this industry.”

THE ADVOCATE

David Tillman was skeptical.

The chair of Campbell University’s Public Health program and an assistant professor on the subject, Tillman is an advocate for rural health in the highest sense, and he has been critical of North Carolina’s pork industry and the negative environmental impact of the state’s 2,300 farms housing more than 9 million hogs (most of them in the eastern part of the state).

But it didn’t take long for Tillman to see something different in Tom Butler. The two met through the various boards they serve on in Harnett County, and Tillman says within five minutes of that first handshake, he knew he had to get him in front of his students. Within two weeks, Butler agreed to participate in a talk Tillman was giving titled, “Toxic Hogs: Ethical considerations and environmental health impacts of industrial farming,” where he shared his innovations and talked about the problems with the industry.

Not long after that, Tillman’s rural health students were spending class time on Butler’s farm.

“For most of us, the day-to-day realities of hog farming are pretty far removed from our pig pickins,” Tillman says. “The truth is that over the last 30 years, as advances in industrial agriculture achieved production levels that weren’t dreamt possible before, there has come a colossal environmental burden of waste and a new threat to the health of our communities.”

“For most of us, the day-to-day realities of hog farming are pretty far removed from our pig pickins,” Tillman says. “The truth is that over the last 30 years, as advances in industrial agriculture achieved production levels that weren’t dreamt possible before, there has come a colossal environmental burden of waste and a new threat to the health of our communities.”

Rolling Stone went into great detail about the negative environmental impact and health impact of the industry in its March 19 magazine article, “Why Is China Treating North Carolina Like the Developing World?” The article pointed to Duplin County, where “future hams outnumber humans about 30 to 1” and where “hogs generate about 15,700 tons of waste daily — twice as much poop as the human population of New York City.”

The lagoons that house this waste are the crux of the article. Hog farmers typically prevent their overflowing by using the waste as a fertilizer and spraying it on crops and in the fields. This technique can create a mist — a repugnant, overpowering odor — that stays in the air and can be inhaled by neighbors, “causing all manner of respiratory and health problems.” Recent hurricanes have also revealed setbacks in an open-air lagoon system. In 1999, Hurricane Floyd flooded much of the eastern part of the state, flushing out the lagoons into local water systems.

Rolling Stone reported that an analysis by the Environmental Working Group found 160,000 people living in and around North Carolina’s top five hog-producing counties may be harmed by pig waste. And those victims are “disproportionately” minorities, according to a study by UNC-Chapel Hill.

In May of this year, a North Carolina jury awarded $50 million to 10 neighbors of a 15,000-hog farm in the White Oak area of Bladen County who filed the first in a series of federal lawsuits against Murphy-Brown/Smithfield Foods, the world’s largest pork producer. The plaintiffs argued that the odors from their nearby farm were so “noxious, sickening and overwhelming,” it was impossible to get it out of their clothes.

A second lawsuit was scheduled for late May.

Butler was a witness in that trial — not for the hog industry, but for the plaintiffs. He explained his covered lagoon system and energy production in court and talked about how his investments have led to a relatively odor-free operation.

“Relatively” is a key word. Butler Farms will never be mistaken for a rose garden. There is the occasional waft of odor when you’re down-wind from the hog house or if the breeze hits just right. But you can also stand in the middle of his lagoon, millions of gallons of pig waste two inches beneath your feet, and smell nothing.

The industry needs to work toward this across the board, Butler says. He feels bad for farmers like him — he says that $50 million lawsuit was never about the farmer — and says too many have taken on debt or increased work demands to worry about becoming environmentally compliant. He told Rolling Stone that contract farmers like him are paid “just enough to make their payments, but never enough to get out of debt.”

“If the industry continues to disregard the health impact of these farms, it will eventually reach the consumer. And the consumer has the power,” Butler says. “If the consumer is bullied or ignored, they’ll eat something else. Heck, I’ve tried some of those vegan or vegetarian diets. They’re actually pretty good.”

That’s not something you’d expect to hear from a man who’s raised hogs for nearly 25 years. But that’s part of the charm of Tom Butler, according to Tillman, a man who fully expected to be at odds with the farmer until he actually met him.

“The most incredible thing about Tom Butler is his vision and heart,” Tillman says. “Tom is out in front of the industry … simply out of a desire to be the best neighbor that he can be to the rural residents that surround his farm. Having covered lagoons is an incredible testament to his heart. The investment into the technology to turn waste into energy is evidence of his vision.”

GIVING BACK

Phil Stokes earned his degree in accounting from Campbell last December and wanted to stick around in the area until he took his Certified Public Accountant exams. In Stokes’ mind, there was only one place to work between diploma and certification: a hog farm.

“My grandfather owned a farm, and I appreciated the land and agriculture, so I wanted to try it out myself,” says Stokes, who’d never driven a tractor before until Butler put him in a big John Deere on his first day. “I also wanted to be on my feet, outdoors and appreciating farm work and labor before I start my career. Plus, I love pigs.”

He does. Stokes has two pet pigs at home — Darlene and Belle — and admits he can’t get too attached on the farm, as these future hams are shipped off to Smithfield after only seven months in Lillington. “We tell them they’re being shipped off to the fair,” Stokes says and Butler confirms. “It makes us feel a little better about it.”

Another reason Stokes wanted to join Butler’s operation was because he liked what he read about his farm — the energy conservation, the environmental stewardship and the desire to do more for the community around them. Stokes and Tillman represent an important Campbell connection for Butler Farms, but the relationship goes far beyond a Rural Health Award and some lectures.

In 2017, Campbell University made a big commitment to rural health in the form of the Rural Philanthropic Analysis, a project launched to better understand rural places and funding practices that are leading the way toward health improvement in these areas. The University recently opened a student-run health clinic for the uninsured (many of its patients are migrant farm workers in the area or men and women below the poverty line). The School of Medicine opened a health clinic in Dunn in 2017 and plans to open a second off-campus clinic in Lillington in the near future.

In 2017, Campbell University made a big commitment to rural health in the form of the Rural Philanthropic Analysis, a project launched to better understand rural places and funding practices that are leading the way toward health improvement in these areas. The University recently opened a student-run health clinic for the uninsured (many of its patients are migrant farm workers in the area or men and women below the poverty line). The School of Medicine opened a health clinic in Dunn in 2017 and plans to open a second off-campus clinic in Lillington in the near future.

The decision to present Butler with Campbell’s inaugural Rural Culture of Health Award last year was a no-brainer, according to Tillman, because his farm and the University have the same goal in mind — better health in underserved communities and a desire to fund projects that will lead to this.

“Tom’s innovative efforts to protect the health of the community and to create sustainable energy are perfect examples of the kind of work that is done every day by folks who don’t think of themselves as public health [advocates], but who help create healthier communities,” Tillman says. “The notion of a ‘culture of health’ challenges us to consider health in all policies and all practices.”

Tillman was at the farm on May 4 for a Harnett County-sponsored dedication ceremony for a new electric microgrid that can run up to 150 homes using energy produced solely by pig waste and solar panels.

This project represents the first time that a North Carolina Electric Cooperatives member’s existing energy resources have been integrated into a microgrid.

Asked why covered lagoons, microgrids and odorless farms are so important to him, Butler goes back to the impetus of his innovative approach.

“It was that neighbor’s phone call,” he says. “Our dream right now is that all of this technology will do away with all the odor and the waste, and this farm will one day have zero impact on the environment. Zero. That sounds like a dream, and it probably is. But we think it’s doable.”