GENERATION AI

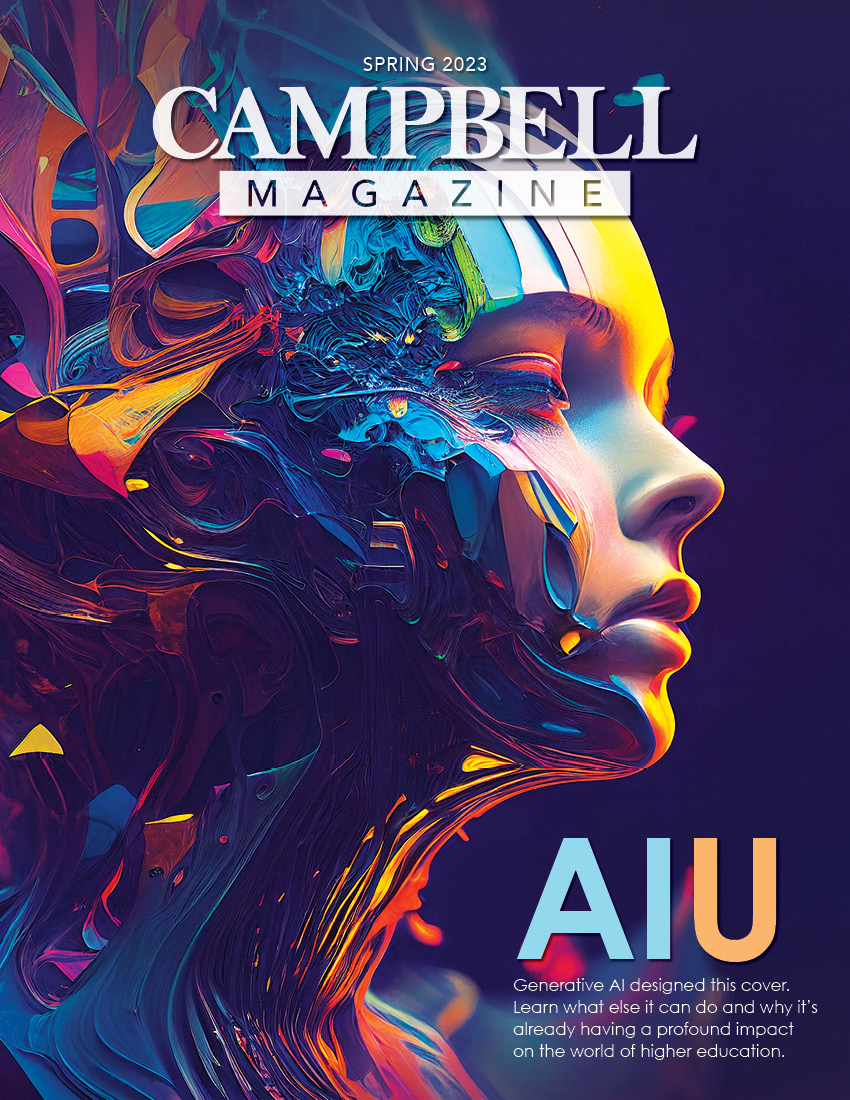

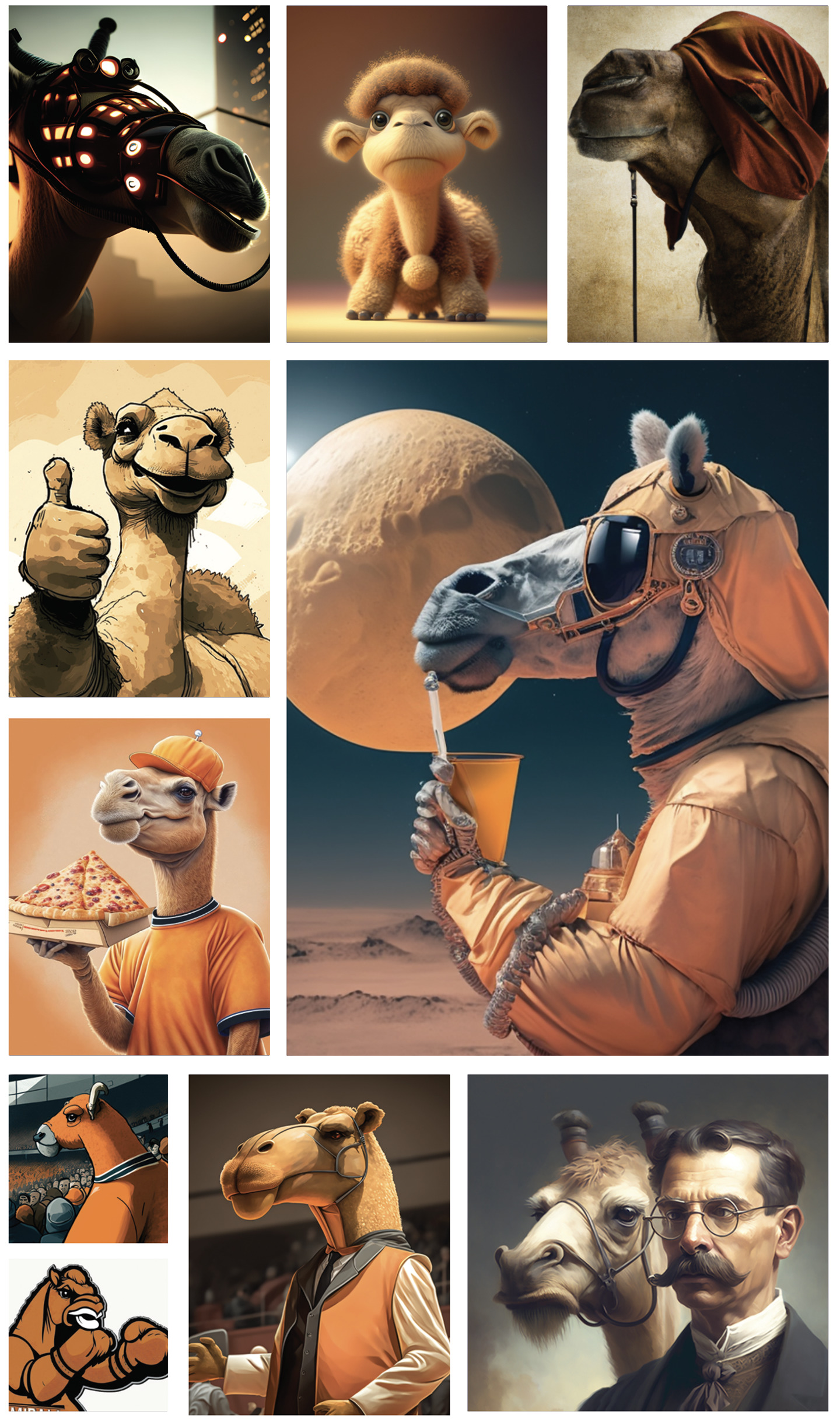

It can pass the bar exam. Write an essay. create detailed images (like this one) in seconds. Artificial intelligence-generated content is the new frontier of technology, and already, the impact on higher education is profound.

Story by Billy Liggett

The one computer in the room is stuck in screensaver mode. The smart phones have all been set aside on the table, glanced at only occasionally by those checking the time. Otherwise, the brain power gathered on this day in a second-story Wiggins Memorial Library meeting room is 100-percent organic.

Four human professors and a human librarian, all sharing a love of higher education and a budding curiosity about recent advancements in artificial intelligence.

Not just AI, but Generative AI. Technology’s “new frontier.” Programs now widely available to professors and students alike, able to create written content, images, music and videos with — considering the relative “newness” of it all — astounding levels of realism and difficulty.

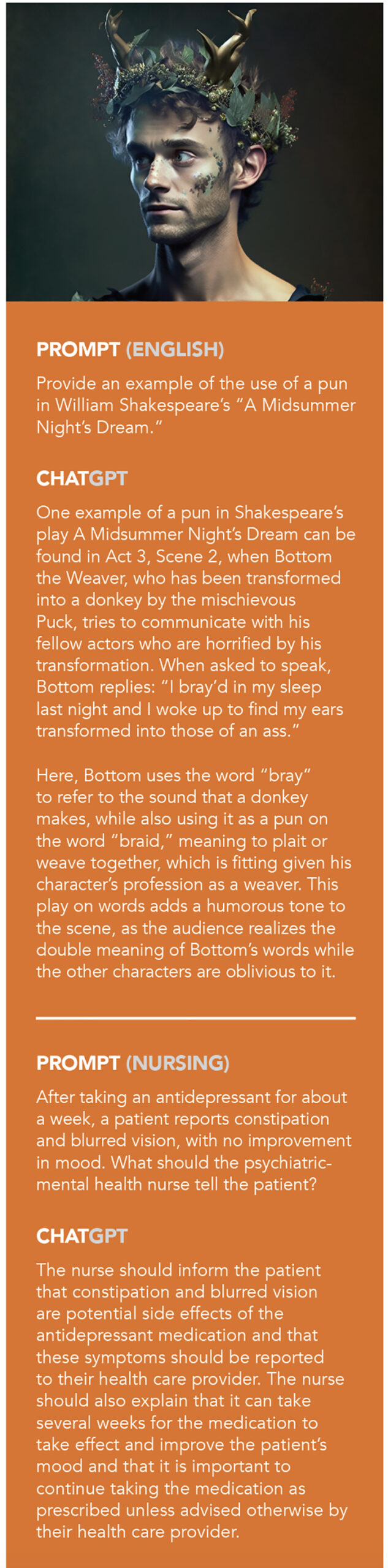

The impact on higher education has been immediate and profound. For the humans in the room — English professors Sherry Truffin and Elizabeth Rambo, communication studies’ Brian Bowman, Justin Nelson from psychology and reference librarian Meredith Beeman — there is cause for concern. Students are already turning to chatbot programs like ChatGPT (and now ChatGPT-4) to pass off complex “written” assignments as their own. Image-generating sites like Midjourney and Dall-E are borrowing from copyrighted photography and art to create digital images within seconds.

But the possibilities overwhelmingly outweigh the fears, at least in the classroom. Rather than seeing it as a threat, educators are discovering how to incorporate Generative AI into their teaching. Many see an opportunity to stimulate critical thinking, to improve writing skills (rather than use AI as a crutch), to improve accessibility and to reimagine the way they assign tasks for their students.

All of these thoughts are shared in the library room where five faculty and staff have gathered for what’s now a 90-minute meeting. Organized by Bowman, the goal of today’s meeting isn’t the creation of new University-wide guidelines or data for a research collaboration. It’s simply a shared curiosity. And this isn’t the only meeting like this happening on campus.

Generative AI is still new, and we’ve barely scratched the surface on its potential.

“My feelings on this have actually changed dramatically in a very short time,” says Bowman. “When I first started hearing about it, the first thing I thought was, ‘My gosh, they can use this to cheat.’ But as I continue to learn more, I wonder how I can partner with the students to better utilize this.

“As professors, we have to understand that our students are going to be using this anyway. So my goal for them is to be able to understand this technology and know how it works. Not necessarily the coding part, but really, how can they use it wisely? What can this lead to? What effect will all of this have on our society?”

01000001 01001001

Artificial intelligence is already embedded in our lives. Our digital voice assistants like Alexa and Siri use it. So does the face recognition software on our phones. The maps in our cars, the shows and products suggested by our Netflix and Amazon apps, the posts that appear in our social media feeds and the programs that simplify online bill paying — it’s all powered by AI.

AI goes as far back to World War II and the “Father of Artificial Intelligence,” Alan Turing. The British scientist solved the “Enigma Code” the Germans employed during the war to transmit coded messages (it’s estimated his contributions saved more than 14 million lives). After the war, Turing gave what’s considered the earliest public lecture on computer intelligence, saying, “What we want is a machine that can learn from experience.” He authored a paper in 1950 titled “Computing Machinery and Intelligence,” which described a procedure now known as the Turing Test — a method of determining whether or not a computer is capable of thinking like a human.

It would be 64 years before AI would pass the Turing Test — in 2014, a chatbot developed by Russian and Ukrainian programmers convinced all 30 judges at a University of Reading event that it was actually a 13-year-old boy.

Nine years later, chatbot software — now known as Generative AI — has become so advanced, some consider the Turing Test to be obsolete. ChatGPT is the second program to have fooled the judges, officially doing so in summer 2022. In the short time since, it’s only become smarter.

And, now, widely available.

In January, ChatGPT reached 100 million active users just two months after its public launch. By comparison, it took the globally popular TikTok app two and a half years to hit that mark. That same month, Microsoft announced a $10 billion investment into OpenAI (creators of ChatGPT) and an AI-powered Bing homepage. In February, Google joined the race with the introduction of its own “experimental conversational AI service,” Bard.

“No field is more likely to be affected by these advances than higher education,” writes Ray Shroeder of the University Professional and Continuing Education Association in a February column for Inside Higher Ed. “The ability to generate text, images, music and other media with clarity, accuracy and adaptability is on target to enhance the way we deliver learning and facilitate access to knowledge. A revolution is underway, and I can guarantee that it will touch your workplace in 2023 and beyond.”

The impact on schools like Campbell University is already “huge,” says Sherri Yerk-Zwickl, Campbell’s vice president for information technology and chief information officer. There are concerns — ChatGPT has already passed a bar exam and earned a solid B on University of Pennsylvania Wharton MBA paper, so there’s the legitimate fear that students will use this to cheat or pass AI’s work off as their own. There’s also worry that ChatGPT will make some jobs in customer service, health care and, yes, academia obsolete.

And there have already been missteps by universities in using the new tech. Vanderbilt University faced backlash after admitting a condolence post on social media after a mass shooting at Michigan State University was written by AI.

But Yerk-Zwickl, like Bowman, is more interested — and optimistic — about how the technology will improve higher education and the student experience.

“We have existing academic integrity policies that state passing off someone else’s work as your own is not acceptable. But we in information technology also have the responsibility of helping people understand these new programs and become aware of what they can do,” she says. “AI’s been a part of all of our lives and a part of education for a while now, but ChatGPT has kind of made people sit up and take notice. And we’re just scratching the surface of what this technology can do. The genie is already out of the bottle, so we need to help people not only understand its capabilities, but train them to use it in a way that is useful and doesn’t disenfranchise others.”

01000110 01100101

01100001 01110010

As is often the case with new technology, students are ahead of the game compared to their professors and the rest of the 30-and-older crowd. According to a January report in Forbes, nearly half of all college students surveyed admitted to using ChatGPT for an at-home test or quiz, and nearly a fourth used the program to write an outline for an essay or research paper.

The same study revealed that roughly three-fourths of all college professors who are aware of ChatGPT are concerned about its impact on cheating, and over a third of them believe the program should be banned from colleges and universities. On the flipside, 5 percent of educators said they’ve used its to help teach a class, and 7 percent have used it to create writing prompts.

Campbell English Professor Elizabeth Rambo says at least two of her students (that she knows of) used it in their research papers last fall, months before it became so widely known. Her colleague Sherry Truffin has seen it, too. Those instances are only going to go up, which has professors on high alert and unarmed when it comes to trusted tools — powered by AI — that can detect AI.

“We have an honor code, and, you know, I’m tired of policing it,” says Truffin. “So when students ask me, ‘But how are you going to know?’ I say that chances are, I’m not. But one of our jobs is to teach critical thinking skills, and they’re not going to develop these and advance by turning in [AI-written] content that simply looks clean enough and close enough.”

Campbell University’s Honor Code has yet to include language concerning Generative AI, but it does state that students should be, among other things, “truthful in all matters” and should “encourage academic integrity among all fellow members of the Campbell community.” Among the actions the University labels as “academic misconduct” are “allowing one’s work to be presented as the work of someone else;” “using words, ideas or information of another source directly without properly acknowledging that source;” and “inappropriately using technologies in such a manner as to gain unfair or inappropriate advantage.”

When academic misconduct is discovered, it’s up to the faculty member to determine the appropriate course of action. With Generative AI still still in its “Wild West” phase of lawlessness, many are unsure how to punish — or even whether to punish — these violators.

And students aren’t the only ones facing temptation, according to Campbell Psychology Professor Justin Nelson, who co-authored the tech-related paper, “Maladies of Infinite Aspiration: Smartphones, Meaning-Seeking and Anomigenesis,” with a Baylor University colleague in 2022. Faculty members, specifically junior faculty, “already feel the pressure to produce something that only rewards the end goal,” he says.

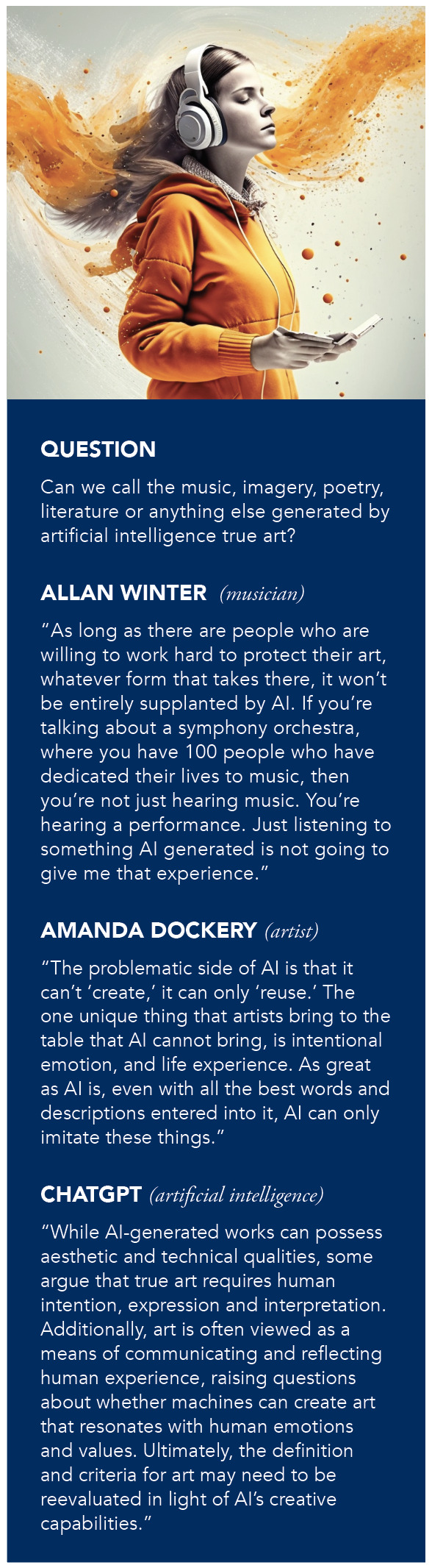

Cheating isn’t the only fear. Artists, writers and others in creative fields see Generative AI as a threat in their careers. There are similar concerns in the legal and health care professions. Speaking of “legal,” that’s the other big worry — Microsoft and OpenAI are currently facing lawsuits from code-generating AI system Copilot, and AI art programs like Midjourney have been accused of infringing on the rights of artists and photographers whose work they’ve been trained on.

“The problematic side of AI art is that AI can’t actually create; it can only reuse,” says Fuquay-Varina artist Amanda Dockery, whose illustrations have appeared in several recent editions of Campbell Magazine. “The issue for many artists is that it steals art without crediting the artists it uses to generate images. I can understand how that can be frustrating for many artists, but there’s the saying, ‘Good artists copy; great artists steal.’ Art has always involved mimicry or theft in some way.”

Fear of new technology and pessimistic predictions on its effect on mankind are nothing new. Destruction of job-replacing machines was so prevalent in England during the Industrial Revolution that the act was made a capital offense —punishable by death — in the early 1800s. The sewing machine, the horseless carriage, the assembly line, the computer, the internet — all of these advances led to fear of human irrelevance in the workplace. A highly publicized Oxford University study in 2013 predicted that half of U.S. jobs would be replaced by artificial intelligence by 2033.

If history is any indication — and it often is — human ingenuity will respond.

For artists and other creatives looking to stay relevant, “survival” will mean learning to adapt and embrace the Generative AI era, says Dockery.

“For some, this is a crippling development, and for others, it will make their career,” she says. “I think the greater challenge for artists is how to see this as a tool to aid in creativity rather than an evil to avoid. The one unique thing that artists bring to the table that AI cannot bring is intentional emotion and life experience.

“As great as AI is, even with all the best words and descriptions entered into it, AI can only imitate these things.”

And as students and the workforce learn to work with AI, professors will learn to adjust their curriculums to not only curb the temptation to cheat, but more importantly, prepare their students to compete in the real world.

“Students are more likely to cheat in high-stakes situations where they are not confident [in their abilities],” says Truffin. “One thing I’m trying to do is develop more low-stakes, build-skills assignments — teaching them to value the processes and steps that go into writing. And certainly in English 101, we want them to develop their skills and their style, become aware of their weaknesses and improve in their writing process.”

“How can we break down what used to be just the ‘end goal,’ to a series of possible assignments that allow us to integrate AI and have conversations about the process?” adds Nelson. “Students need to understand that the process is just as, if not more, important than the end result.”

01100110 01110101

01110100 01110101

01110010 01100101

It’s another day and another room — this one on the second floor of the Oscar N. Harris Student Union — and another group of faculty and staff are gathered at a table to talk AI. There’s Curriculum Materials Librarian Jennifer Seagraves, (now-retired) Director of Academic Computing Allan Winter and Instructional Technology Consultant David Mulford — all three deal with computing and AI on a daily basis, and all three are both fascinated and curious about this next generation of generative technology.

Mulford wastes absolutely no time getting deep on the subject and bringing up the name Ray Kurzweil, the American scientist, inventor and futurist whose books (published in the 1990s and early 2000s) have tackled the history of AI, his theories on AI development and the thought that machines could one day develop artificial “superintelligence.”

“Ray believes that at some point, you’re going to be able to upload your brain into ‘the Borg’ and live on,” Mulford says. “He calls it the ‘singular singularity.’ But there are philosophers and others who are educated on this who think this is complete bunk. No. 1, we don’t know how to do it, and No. 2, what is the soul? The idea questions what it even means to be alive and human, and I don’t think sentience can form in something that can’t think or feel or perceive things like a human can. Our brains are so much more powerful than an algorithm. Our brains are millions and millions and millions of algorithms working together. And each brain is unique.”

“Ray believes that at some point, you’re going to be able to upload your brain into ‘the Borg’ and live on,” Mulford says. “He calls it the ‘singular singularity.’ But there are philosophers and others who are educated on this who think this is complete bunk. No. 1, we don’t know how to do it, and No. 2, what is the soul? The idea questions what it even means to be alive and human, and I don’t think sentience can form in something that can’t think or feel or perceive things like a human can. Our brains are so much more powerful than an algorithm. Our brains are millions and millions and millions of algorithms working together. And each brain is unique.”

Again, heavy stuff.

But the conversation is fun. It’s insightful. And it’s all brought on by the recent advances in Generative AI and — for them — the impact it’s having on their workplace. But where fears of student cheating and AI-inspired shortcuts made up a big chunk of the conversation in Wiggins Library, this room is more focused on the possibilities (to be fair, optimism did abound in the other group, too).

In just the past few months, attitudes toward Generative AI in higher education have tilted toward the positive. An April poll of higher ed professionals published by EDUCAUSE Review said those who were “optimistic or very optimistic” about the technology in their schools rose from 54 to 67 percent. Neutrality fell from 28 to 18 percent, and those who were “pessimistic or very pessimistic” dropped from 12 to 11 percent.” Over 80 percent felt Generative AI will “profoundly” change higher education in the next five years, and nearly 60 percent said it will make their jobs easier.

Seagraves sees it as a huge asset for librarians, a helpful tool that can help her teach information literacy and information fluency skills to her students and help her assist faculty with new ways to research and use certain databases in their classrooms.

“It gives our faculty the opportunity to make their connections with students stronger,” she says. “Believe it or not, it might make learning more human. Use this as an opportunity to assess your students and leverage AI to make the learning experience more personal to them. I think one of the reasons ChatGPT has triggered all of this conversation in higher education is because this AI can really help students. We have to look at it in that light.”

Winter agrees, calling these programs a “fantastic way” to get students leaning toward “the higher order thinking skills.”

“I think back to when I was a student, and we spent as much time learning how to do a research paper as we did on the subject matter of what our research topic was going to be,” he says. “How much better would it have been if we could have absorbed and synthesized and otherwise learned more of that content matter. Certainly, it’s important to be able to write well and be discerning about what you find in your research process. But at the same time, you have a tool now that presents some possibilities of really approaching those higher order thinking skills in the analysis and the synthesis, and AI can be applied in that regard. And not necessarily just be used by a student to write the paper for them.”

Up in Raleigh, Generative AI and its many debatable legal ramifications has been a hot topic in classrooms at the Norman A. Wiggins School of Law and in the school’s Innovation Institute. Professor Lucas Osborn, an expert in intellectual property law, says the legal community is trying to keep up with the technology — questions of whether programs trained on other artists’ work that “borrows” from their styles (and even their art) are guilty of copyright infringement have complicated answers and make for great discussions.

But these discussions go far beyond the “what ifs.” Attorneys and other legal professionals see AI as a way of making their jobs easier. For example, if AI can write a clear, accurate legal brief, then why can’t attorneys save time by using a tool like this? Many firms have turned to AI programs like ClearBrief, which is designed to “strengthen legal writing by instantly finding the best evidence in the record to support a legal argument” and runs about $125 a month.

These programs are saving lawyers time and money. They’re also useful for law professors.

“The way we have to write our scholarly articles in law, we usually have to give a bunch of background that we already know. There’s only so many times you can rehash the same background before it gets a little boring and routine,” Osborn said. “So how great would it be to have something where you could say, ‘Hey, give me the overview of this area of law,’ which can save me 20 to 30 minutes? If this thing can craft the first pass of a legal brief, then great, let’s have it do this, and I’ll review it and clean it up.

“If it can save the client money and time, then I see it as a helpful tool. It’s like a calculator, and we should be teaching our students that this technology is out there.”

Admissions departments at colleges and universities across the nation are using AI to rate an applicants’ potential for success based on how they respond to messages (one service claims it’s 20 times more predictive of student success than demographics alone). Other chatbot services stay in constant communication with prospective and accepted students and “nudge” them toward taking the next steps in their enrollment process. Georgia State University is considered a pioneer in the use of admissions chatbots, and its program, “Pounce,” has reduced the number of students who enroll in the spring but fail to show up in the fall by 20 percent since 2016, according to an article in The Chronicle of Higher Education.

Back on main campus, on the second floor of the library, talk has shifted from the worries to the possibilities. Beeman suggests professors would be paying their students a disservice to outright deny the existence of Generative AI or deny its use in the classroom. Rambo says that despite concerns that students will use it to write papers, perhaps professors can ask students to evaluate AI-generated writing (in turn, AI can evaluate and catch errors in their own writing).

And Nelson suggests that AI will force professors to challenge students to reflect on or critically analyze things — like a classroom discussion — that AI would have no way of knowing. “If I ask them to tell me about a theory of socialization, they can find that anywhere,” he says. “But if I ask them to tell me about how something applies to their own life, then their answers become personal, which AI can’t do.”

Donald Flowers, network security administrator for Campbell’s Information Technology and Security department, has this advice for professors and students: Embrace AI. This is only the start, he says. It’s only going to get better and more useful from here.

“Emphasize the importance of sharing this with our students,” he says. “It’s not going to define who you are, and it’s not going to encourage them to not be who they are, but still … embrace it. Don’t reject it. I don’t know why, but certain generations have a tendency to turn away from something new, because they don’t feel like it will apply to them or they’re not sure about it. But as teachers and mentors, it’s our responsibility to show our students what this is and the right way to use it.”

Yerk-Zwickl agrees — rather than treat AI as a taboo in the classroom, everyone benefits if professors recognize the value in programs like ChatGPT as tools for idea generation. Embracing Generative AI will mean a big shift for some faculty members, she says, and it falls on members of the IT department and library staff to help them along as they figure it out.

“I’m an optimist by nature, so I am optimistic about this,” she says. “But I also try to be realistic about the potential for harm that this can do. I think we, as an institution, need to prepare our students for that world that they’re going to be living in. I think we have a great opportunity to do that. It’s an exciting time to be working in higher education.”