The mission statement continues to guide Campbell Divinity 25 years after its founding

By Kate Stoneburner

Recalling the beginnings of Campbell Divinity School, founding Dean Dr. Michael Cogdill says one of the biggest challenges was coming up with the words to describe the school’s mission.

The words needed meaning. They needed to last.

Cogdill, Dr. Bruce Powers and then-Provost (and future president) Dr. Jerry Wallace gathered every Monday at 5 p.m. for an early dinner and would work until midnight or later for eight months straight going over curriculum, faculty, accreditation and funding while planning for the school. But just as important to them was the mission statement — the true constant that would guide the school for decades to come.

Their shared vision was threefold. They prayed they would develop a school that would nourish both minds and hearts, that would maintain close relationships with churches, and that would teach in such a way that students would graduate ready to go into ministry.

Those hours of prayer and work formed the mission statement: To provide Christ-centered, Bible-based and ministry-focused theological education.

“This is the DNA of this Divinity School,” says Cogdill, who stepped down as dean in 2009 and retired from higher education 10 years later. “To love the Lord with all of our hearts and minds, to learn all we can about the Bible and to serve God’s people. We encourage our students to make this commitment their personal mission statement.”

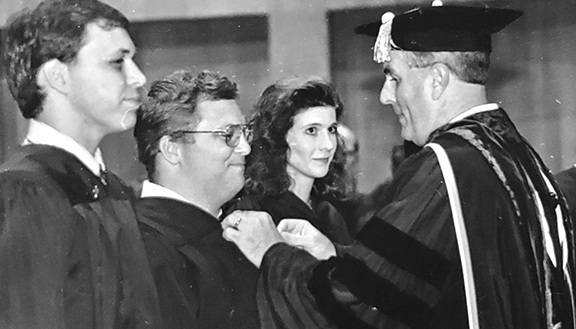

To his knowledge, Cogdill wore his Divinity School pin — a Celtic cross over the globe, representing the school’s mission — every day during the 20-year career that followed the school’s founding. The pin is given to students upon their class commissioning, and it represents daily commitment to that mission statement.

“Christ-centered, Bible-based, ministry-focused” has indeed stood the test of time.

When the school sought reaffirmation of accreditation recently, it surveyed alumni and students about changes needed for improvements. On top of the list of things to not change was the mission statement. It remained the same, even as the school continued to add new programs, faculty and a chapel to call home for worship and classes.

“It has served us and guided us well,” Cogdill says, “and the timelessness of such a statement will continue to chart the path of the school for years to come.”

Back-to-back events in September of 1996 would have a big impact on Campbell University and Harnett for years to come.

The first was Hurricane Fran, which hit the North Carolina coast, barreled up the Cape Fear River, dropped nine inches of rain in Harnett county and caused extensive damage to Campbell’s main campus, closing it for days. So severe was the impact of the hurricane that the name Fran was retired in remembrance of its severity.

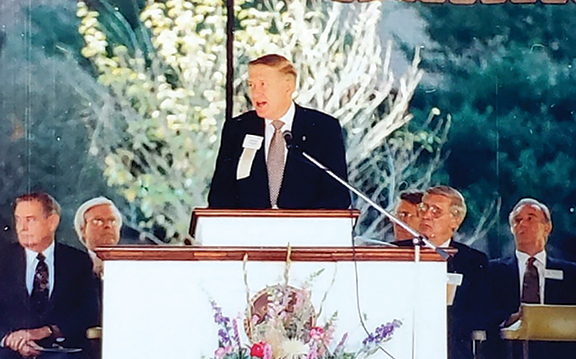

The second was the opening of Campbell’s sixth school — the Divinity School — which held its commissioning service just days after the storm. With no power on campus, the first Divinity students gathered for classes at Memorial Baptist Church down the street. The packed sanctuary and sense of hope — even in the aftermath of a storm — made for a memorable beginning.

For Cogdill, the true beginning of the Divinity School was much earlier. In 1992, the University began a feasibility study to determine if Campbell should add a school for theological education. Prior studies in 1969 and 1975 had led the board of trustees to conclude that the time wasn’t right, but in 1995, Cogdill and Powers were asked to join Wallace to develop a plan for the school.

Eight months later, the board unanimously approved the plan for the Campbell Divinity School in September of 1995 and on Oct. 22, 1995, the school was publicly announced at the Baptist State Convention, with an official opening date set for fall of 1997. But a new problem arose — interest in the new school, particularly from students of religion and philosophy, was so great that the question of opening earlier was raised. Cogdill and Powers, who had been named dean and associate dean, went back to their Monday night meetings to shorten an 18-month timeline to 10 months instead.

The Divinity School officially opened on Aug. 19, 1996, initially offering elective courses and introducing a formal curriculum the following year. Thirty-five founding students enrolled in the first year. These students — and those who enrolled in the fall of 1997 — constituted the charter class of 84 students.

The school has continued breaking records ever since its speedy opening, taking only six years to receive accreditation from the Association of Theological Schools rather than the typical eight and surpassing its goal of 200 scholarships two years early in 1998.

An outstanding cadre of founding faculty members helped launch the new school. Professors Malcolm O. Tolbert, Thomas A. Jackson, Delos Miles, James W. Good, Ginger S. Graves and Jo Ann Stancil were among them. On staff, Clella A. Lee, a graduate assistant, became the first Divinity School director of admissions and student life, and she was instrumental in beginning support services and an assimilation process for new students.

As dean and associate dean, Cogdill and Powers made a commitment to do whatever it took to make the school succeed. This commitment was shared by their spouses, who took the long hours in stride. It was also shared by Jerry Wood, present-day associate vice president for institutional advancement and planned giving, who joined Campbell as director of church and community relations. The foundation he laid to secure resources for the school is still evident today — the Divinity School is Campbell’s highest endowed school, with 200 scholarships and a chapel built with the help of more than 1,900 donors.

The Robert B. and Anna Gardner Butler Chapel was dedicated in 2009, and now stands as a tangible representation of Campbell’s commitment to engage in faith together as a community. In Cogdill’s mind, the chapel was his last great effort as dean of the divinity school.

“We wanted a chapel that would be open, and bright, so that as we worshipped we could look out and see the students outside the space,” he says. “It was important that the campus around us did not feel like an interruption, but the very reason we are here — to love and serve our neighbors.”

Soon after the chapel’s opening, Cogdill handed the reins to Dr. Andy Wakefield, the school’s second and current dean, who was one of its first professors.

Wakefield understood the vision of the school and the qualities that made Campbell Divinity stand out — the accommodation of commuting students, for one thing.

A commuter himself when he first started as a professor, Wakefield was simultaneously working on a PhD. at Duke, serving a church and living in Chapel Hill. He understood that the new school needed to be accessible to both on-campus students and commuters.

Historically, students studying for ministry fields tend to be older than traditional undergraduates, already working or pastoring and even supporting families. Campbell Divinity designed its programs with block scheduling to make scholarship fit in with real life.

Even in his early days at Campbell, Wakefield noted a unique emphasis on belonging to a church, both for students and faculty members. At the time of the school’s founding, the model for education kept academics and service separate. It was rare to see a professor who was also a pastor.

“Students studied the New Testament and developed all the right theories about Bible historicity for a few years, and only then would they spend time serving a church and learning how to put knowledge into action,” Wakefield says. “But because of the timing of its founding and careful thought from the beginning, Campbell was able to integrate study and working with people into the fabric of its programs.”

As a school with a Baptist heritage and a strong religion department, Campbell already had strong relationships with churches, particularly in eastern North Carolina. In the fateful meetings that steered the school’s founding, an intentional decision was made: Campbell would not simply educate for the sake of education, but would educate for service. It would be known for producing graduates who are ready to serve meals and sit with the grieving, who had practiced baptizing and understood church tax regulations.

They could write articles and commentaries if they chose to, of course, but they would have a practical faith as well as an academic one.

“Being able to step back from the discourse around scripture is so essential,” Wakefield says. “There are impossible questions — problems without answers in the back of the Bible — that our students encounter. When they come across them, they need to be able to say, as I often say to them, ‘So what? What does this mean for my ministry?’”

There is a spiritual benefit to practical ministry education as well, and it is that students who get hung up on the same mysteries of life that have puzzled biblical scholars (and humans throughout the ages, for that matter) are able to reach through the academic gray area to love and serve their neighbors.

“I don’t get up in the morning and think to myself, ‘If only I knew exactly who wrote the Gospel of Matthew and when, my day would be so much easier.’ I do my best to teach students that it is OK to live with some mystery. And that’s been a hallmark of this Divinity School — that we have always combined a deep seriousness about our faith with complete willingness to explore and absolute readiness to say, ‘I don’t know.’”

As he worked through his own journey of vocational discernment before teaching at Campbell, Wakefield distinctly remembers a desire to both teach as a professor and still serve and pastor a church in a significant way. Today, he is passionate about programs — such as the Master of Arts in Faith & Leadership degree — that prepare students to develop strong theology and exercise their faith in workplaces from insurance offices to restaurant kitchens.

“Not everyone who graduates from Campbell Divinity School will be called to work in the church, but they are called to draw nearer to God and understand their faith,” he says. “They will know what it looks like to exert your faith wherever you are — to be Christ-centered, Bible-based and ministry-focused.”

TIMELINE