Cover Story | Fall 2020 Campbell Magazine

AND JUSTICE FOR ALL

Students of color at Campbell Law School know they’re entering a field that hasn’t always been just for people who look like them. They also know that if anybody can change the system, it’s them.

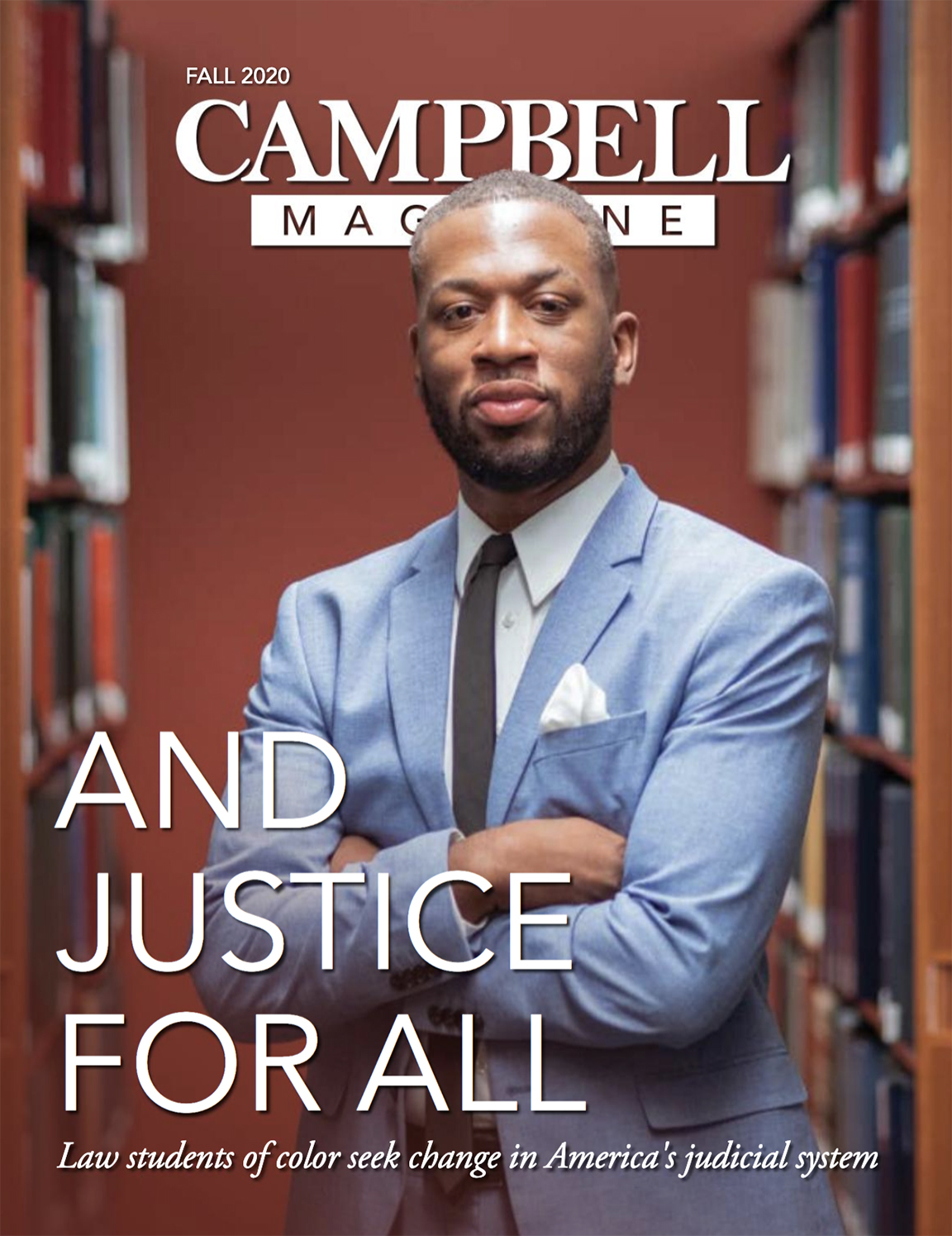

Story by Billy Liggett | Photos by Ben Brown

Black people represent roughly 12 percent of adults in the United States, yet they make up 33 percent of the nation’s prison population. White people, meanwhile, account for 64 percent of adult Americans and 30 percent of its prisoners. Even more disheartening: One out of every three Black boys born today can expect to spend time in prison at some point in their life.

Look beyond the numbers and you’ll find real people impacted by them. You’ll find young women like Morgan Swink.

Born to a 17-year-old Black father and a 16-year-old white mother, Swink was a casualty of her nation’s legal system from the start. Her father had yet to turn 18 when he was arrested for selling drugs and sentenced to five years in prison.

It was his first offense.

“I have pictures of me at 3 or 4, visiting him in prison with my grandparents,” says Swink, now a 26-year-old mother of two. “It had a big effect on my entire family. A lasting effect. Even when he got out, when you’re a criminal, it’s something that is hard to escape. You can’t get a job. It’s hard to start a life. And unfortunately, it wasn’t his last arrest. Five years is a lot of time when you’re that young.”

That experience can send a child in a number of different directions in life — and statistics suggest few of them are positive. But Swink saw her father’s plight and was inspired to choose a better path. She saw an unfair system and decided she wanted to change it.

After earning her undergraduate degree from the University of North Carolina-Chapel Hill, Swink was accepted into Campbell University’s Norman Adrian Wiggins School of Law. Now entering her third and final year, if she goes the criminal defense route, she’ll have an opportunity to defend young men and women like her father.

The weight of this responsibility isn’t lost on her.

“Being a person of color, and because of my experience, I feel like I can empathize better,” says Swink, from Albemarle. “I’ve heard too many stories from Black people who say their public defenders didn’t give them the time or energy their cases deserved. And just from the start, if a Black person sees another person of color in the room defending them, that gives them more hope moving forward. It gives them more trust.”

While Black people represent roughly 33 percent of the U.S. incarcerated population, they make up just 5 percent of the nation’s lawyers. White people, on the other hand, account for 64 percent of adult Americans and 85 percent of their attorneys.

Swink is part of a small, yet growing group of Campbell Law students looking to close this gap. Most are members of the school’s Black Law Student Association, created to provide support and networking opportunities for students of color. Some made history just last year by becoming the first Campbell team to win the Constance Baker Motley National Trial Competition, hosted by the National Black Law Students Association — besting several historically Black universities in the process.

These students will enter their careers during a crucial time in their country’s civil rights history. The death of George Floyd after being detained by Minnesota police officers in May; the death of Breonna Taylor, a Kentucky EMT shot to death in her home by an officer executing a no-knock warrant in March; and the death of Ahmaud Arbery, a Georgia man confronted and killed by three white men as he jogged through their neighborhood in February; created a new movement of Americans — of all races — protesting systemic racism and inequality when it comes to law enforcement and the nation’s criminal justice system.

Future lawyers like Morgan Swink, Melvin Holland, Justin Lockett, Monica Gibbs, Alyssa McPike and Darius Boxley have joined this movement — bringing not only their experiences as people of color and people of diverse backgrounds to the debate, but an education and a mindset that comes with knowing the law and understanding the inner workings (and faults) of the judicial system.

If anybody can make a difference and change the system, it’s people like them.

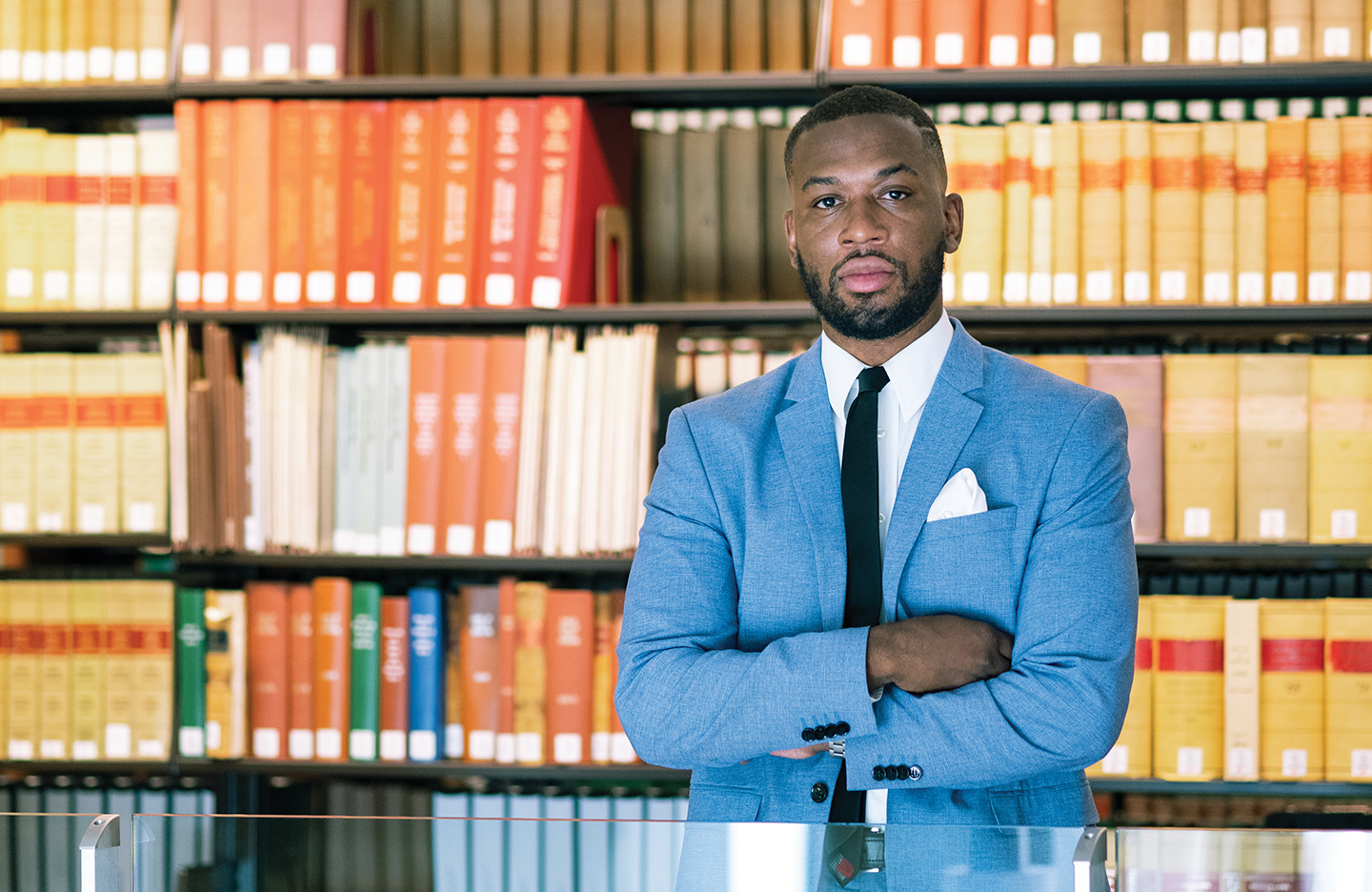

MELVIN HOLLAND

THE TALK

The white, unmarked van came to a screeching halt when five police officers wearing SWAT team gear and brandishing automatic rifles jumped out and ordered Melvin Holland and his father to drop to the ground.

The two men were trying to visit a friend’s apartment in Maryland and had to drive around the complex a few times to find a parking spot, because they didn’t have gate access.

On their knees, their hands behind their heads and heavy weaponry pointed at them, Holland and his father were peppered with questions about a car theft and “chop shop” ring they knew nothing about. The officers revealed that two men who matched their descriptions were stealing cars from the apartment complex and parking in the very spot they were in. Holland and his father were interrogated by the officers until they were satisfied it was a case of mistaken identity.

Melvin Holland was 13.

“I can still visualize it right now — the whole scene, being accosted like that and having no idea why it’s happening,” says Holland, today a second-year Campbell Law student. “I’ll never forget it.”

Holland’s father was calm during the entire event. He had to be, for his son’s sake. He later explained to his son that they were racially profiled — a man and a boy, both about 5-foot-6, who were swarmed because of the color of their skin.

“We didn’t even look like the two men who were doing that,” Holland says. “We were just in the wrong place at the wrong time. We were lucky nothing worse happened. But it changed my mentality, and even today, I can’t walk around a downtown area — or park in an area away from where I’m supposed to be — without looking over my shoulder. It’s something I’ve never been able to escape.”

Before then, Holland’s father had never given him “the talk” — a phrase that for most means a talk about the birds and the bees and not SWAT team encounters. For young Black men and women today, “the talk” focuses on how to act when confronted or questioned by a law enforcement official. The unwritten rules: Keep your mouth shut … don’t get into an argument … keep your hands in plain sight … no sudden movements … don’t run … don’t resist … stay calm …

“We talked about our incident,” Holland says. “He just said to always be compliant. If the police are wrong, you need to hope they catch it. If you escalate the situation, they’ll forget why you’re there to begin with. Be as 100 percent as you can be on your end, and if anything happens, don’t let it be your fault.”

George Floyd’s death in Minnesota not only inspired a new Civil Rights movement in this country, it shined a massive spotlight on what Holland calls 400-plus years of systemic racism in the United States, going all the way back to slavery in the 1600s, long before the original 13 colonies became a nation.

The Civil War may have led to the end of slavery, (the ratification of the 14th Amendment in 1868 granted equal protection to African Americans), but “freedom” was soon overpowered by local and state Jim Crow laws that essentially allowed segregation of schools and businesses and marginalized voting rights for people of color. Many law enforcement agencies in the early 1900s (and organizations like the Ku Klux Klan) were called on to enforce these laws, sometimes with brutality, particularly in Southern states.

Jim Crow cast a pall over much of the 20th Century in the U.S. through the 1960s. Holland says Black people were unequally victimized by the War on Drugs in the 1980s and the push for mass incarceration in the 1990s. From 1980 to 2015, the nation’s prison population more than quadrupled, from 500,000 inmates to more than 2.2 million.

Holland — an accomplished musician (he’s bassist for a rock band in Durham) who studied music at UNC Greensboro — pivoted to law school after graduation because he saw it as an opportunity to help his community and exact change on a broken system. He says he wants to be a public defender, to help families who experience trauma. To help first-time offenders who don’t deserve long sentences. To help people arrested while exercising their right to protest.

“It’s all about giving back,” he says. “That’s my whole purpose in everything I do — to help somebody who needs it and maybe can’t afford it. Whether it’s teaching them music or representing them in court. To me, that’s what’s important.”

One subject that has fascinated Holland during his time in law school is qualified immunity, a doctrine that grants government officials immunity from civil suits unless the plaintiff can show that official violated “clearly established statutory or constitutional rights of which a reasonable person would have known.” Or as Holland puts it: “In a nutshell, it says there has to be a prior case that sets a precedent. If there’s not … you’re facing an uphill battle in court.”

The U.S. Supreme Court introduced qualified immunity in 1967, at the height of the Civil Rights Movement, in the case of Pierson v. Ray — where 15 Episcopal priests (three of them black) tried to enter a coffee shop in Jackson, Mississippi, before they were stopped by two police officers who asked them to leave. After refusing, all 15 priests were jailed, and five of them later filed suit. The suit made it to the highest court before it ruled that although the officers’ actions were unconstitutional, they were excused from liability “for acting under a statute [they] reasonably believed to be valid.”

Over the past 20 years, defense attorneys across the nation have increasingly turned to qualified immunity in cases involving the use of excessive or deadly force by law enforcement officials, making it “a nearly failsafe tool to let police brutality go unpunished and deny victims their constitutional rights,” according to a recent Reuters article.

Holland wants to fight these doctrines that have historically been unfair to people of color. He says the recent Black Lives Matter movement has exposed these “loopholes” in the law.

“I think more people are informed or are willing to inform themselves about the history that’s led up to why Black people feel the way they do in this moment,” he says. “We need allies. We need smart people to understand that we’re not just making this up. Change starts with us; it won’t work if it starts from the top down.”

MONICA GIBBS

RESTORATIVE JUSTICE

The daughter of a white mother and a Black father, Monica Gibbs describes herself as both a “light-skinned African American” and as “white passing.” White people, she says, often have a difficult time telling that she’s biracial. Black people, however, usually “see it” immediately.

She’s experienced acceptance from both sides. She’s also experienced racism from both sides.

It’s a unique perspective, and during this year especially, she finds herself both a voice for oppressed people of color and a “white ally” for those struggling to be heard.

“I feel the weight of it,” says Gibbs, a native of the coastal town of Englehard, North Carolina, entering her third and final year at Campbell Law. “My government documents say I’m Black, yet I have so many of the privileges of ‘the oppressor’ in the eyes of other people of color. I feel very recognized by the Black community, but I have an awareness to always recognize that just because of the tone of my skin, I have privileges that others don’t have. It’s absolutely affected my experience.”

Gibbs considers herself lucky. She’s attended a predominantly white private high school in Raleigh and was able to attend Campbell for undergrad. But she’s seen young people of color who were not as fortunate.

“A minority child is more likely to be born into a family that has not as much wealth or opportunity,” Gibbs says. “Statistics show a Black child who doesn’t come from the greatest community, doesn’t attend the greatest school and doesn’t come from a family where their parents are together … they have to fight so much harder in life. [The fight] can come out as aggression toward others. They get into arguments at school. They don’t know the value of an education.”

And all it takes is one time to crack, Gibbs says.

“An argument with another student becomes a fight, because this is how you were raised to deal with issues. You weren’t taught how to love or communicate in a healthy way. It just takes that one fight, and then they have a record. Children as young as 9 to 11 end up in court rooms. Then detention centers. And it looks sad … seeing what’s essentially a prison with a bunch of kids in it.”

Gibbs is passionate about youth advocacy and the counseling side of the law. She’s also passionate about her involvement in Campbell Law’s Restorative Justice Clinic. The program, led by professor Jon Powell, takes in juvenile offenders — and those who have been affected by the crime or disruptive behavior — and fosters collaborative healing, rather than punishment. Law students like Gibbs engage all involved parties in dialogue to address the violation, how it occurred, why it occurred and what happened as a result. The project aims to discover how people and communities are hurt as a result of crime, and seeks to find the best solution to repair the damage that has been done.

Approximately 85 percent of cases referred to the Restorative Justice Clinic are successfully mediated, resulting in both parties coming together for a face-to-face meeting to address and satisfy their needs as a result of the incident. Fewer than 5 percent of the young men and women who successfully completed the process between 2004 and 2010 reoffended.

“I’ve fallen in love with the clinic and seen the impact it has on people’s lives,” says Gibbs. “When students complete the program, they’re a whole new person. I’ve seen students come in after altercations find common ground and become friends again. They’re grateful they have someone who believes in them.”

Gibbs credits Powell and Law Clinic Policies Program Manager Joia Caron for the program’s success and for fostering something that’s made a direct impact on the community. And she’s thankful she gets to take part in something so meaningful so early in her career. “I wanted a law degree, because I feel I’m meant to do something good in this world. I enjoy doing the research and learning more about issues that are important to me. Along the way, I’ve learned more about myself.”

She’s still learning about herself, especially over the last few months — dealing with feelings of “looking like an ally, but being a minority.” She’s struggled with the notion of being an advocate for people of color, even though she doesn’t necessarily share all of their issues.

One of her favorite things about the Restorative Justice Clinic is that it makes people talk and share their feelings. It creates conversation, and that conversation leads to healing.

The same can be said about the Black Lives Matter movement, Gibbs says. It has people talking — people who maybe previously weren’t aware. Gibbs points to conversations happening in her personal life — her fiancé is white, and his family has asked her questions about everything from Confederate statues to recent protests.

Standing at the spot where one of those Confederate statues once stood in downtown Raleigh — just blocks away from Campbell’s Raleigh campus on Hillsborough Street — Gibbs reflected on the progress that’s been made in the last few months.

“I was at the protests,” she says. “Right outside of the state capitol building — a place that promotes justice — people were being pepper sprayed. At first, I felt powerless … I have a degree and years of training, and I couldn’t access them. But I learned there are different ways I can help. I can educate others on what their rights are. I can advocate for them. I can be their ally. I can help by being their voice.”

JUSTIN LOCKETT

LAWYERS OF COLOR

Ask Justin Lockett about the history of African Americans and the nation’s judicial system, and an encyclopedia of knowledge is unleashed. Dredd Scott v. Sandford, 1857. Plessy v. Ferguson, 1896. Brown v. The Board of Education of Topeka, 1954. All landmark U.S. Supreme Court decisions and each of them representing important defeats and (in the case of Brown) victories for people of color in the United States.

Lockett knows the cases inside and out. He knows the years, the parties. And he knows that when it comes to the law and law enforcement, history hasn’t always been on the side of Black people.

Lockett wants this to change, and he wants to be part of that change. It’s why he’s interested in politics. It’s why he’s passionate about the Black Lives Matter movement. And it’s why he enrolled in law school at Campbell University.

“I was born in 1996, so I didn’t know segregation. I didn’t know Jim Crow. I’ve never been arrested for drinking out of the wrong water fountain,” says Lockett, a second-year student. “I don’t know any of that personally, but I know that historically. And I know it’s part of my heritage and my ancestry.”

Those aforementioned Supreme Court cases — those were real cases involving real people facing real issues, he says. And in some cases, they led to real change. They’ve inspired Lockett to fight for more change at a time of real civil unrest in the country.

“I want to be part of that change,” he says. “I want to make society more fair for everybody.

I looked at the legal field and law school because I knew I could work on my writing skills, become a better advocate and become a better speaker in social settings. My overall big goal is simple — I want to enact positive social change for African Americans. They need civil protections that just aren’t there right now. They need an advocate willing to stand up for them.”

That change starts from within. It starts with more young men and women like Lockett going to law school and seeking careers in the judicial system. Unfortunately, people of color are currently and have historically been woefully underrepresented in America’s courtrooms.

According to a 2017 study published by the American Bar Association, law firms are not making substantial progress in hiring and promoting minority lawyers, even though minority law school enrollment is on the rise. Nearly 85 percent of lawyers at more than 300 firms surveyed in the study were white, a number that “had not meaningfully budged in three years.” Only 4 percent identified as Black.

According to the Minneapolis-based nonprofit Twin Cities Diversity in Practice — an organization dedicated to making the legal community more inclusive — the shortage causes people of color to be underrepresented in courtrooms, and this lack of diversity has a profound effect on the dynamic between lawyers and their clients. A 2011 study of the New York County District Attorney’s office found that Black defendants were 19 percent more likely to be offered plea deals that included jail or prison time. Another study from 2010 found that state and local prosecutors were trained to exclude people from jury pools because of their race (and do so while concealing any racial bias).

Getting more people of color as attorneys and judges in America’s courtrooms starts with getting more people of color in law schools. While the number of minorities enrolled in law schools across the country rose in 2018, Black students still face a tougher road to enrollment than their white counterparts, and for a number of reasons — law school tuition chief among them. Black students also tend to score lower on the Law School Admissions Test (LSAT), which affects their ability to earn scholarships when they can’t afford tuition.

This summer, Noth Carolina Gov. Roy Cooper appointed N.C. Supreme Court Justice Anita Earls and Attorney General Josh Stein to lead a task force aimed at developing solutions to ensure racial equity in the state’s criminal justice system. A step in the right direction, but Lockett wants to see more enthusiasm from state and national leaders to match the enthusiasm currently seen at the grassroots level.

“Here’s my problem,” he says. “You see our communities pleading for change, and that’s very good … I appreciate that. I see people speaking out. But as you walk up the chain, you see individuals in the White House, in Congress and at the federal judiciary, and you don’t see that same enthusiasm. We need judges to start looking at qualified immunity. We need to hold people accountable for their violent acts and their racist acts, and we need this support from the top tiers of our government.”

It’s no surprise politics are a possible future for Lockett, who feels like he’s in the right place at the right time as a movement builds around him.

“The best thing I can do at this moment is keep bettering my skills as a writer and as an advocate,” he says. “Get my JD, pass the bar and use my skills to enact change in court cases and help my community.

“I want to be an asset for the cause.”

ALYSSA McPIKE

MODEL MINORITY MYTH

Alyssa McPike is a proud Filipino American. And she’s well aware of the fact that Filipinos and other Americans of Asian descent haven’t been as quick to back the Black Lives Matter movement or become vocal advocates for their Black neighbors.

McPike even points out a “very big problem” with anti-Black sentiment in her community, particularly from older generations. This divide in this country can be traced back to the 1960s and the idea of the “model minority myth,” or the idea that Asian Americans were viewed as the “good minority” — more successful, better educated and more “inherently law-abiding” — by the majority.

“I’d say for the most part, Asians aren’t against the Black Lives Matter movement, but they are very silent about it, too,” says McPike, a third-year student at Campbell Law. “Colorism runs deep within the Asian community — for example, the skin whitening industry is really huge [$24 billion industry in the U.S. alone] — and as long as industries like that exist, it keeps perpetuating colorism and the idea that the lighter you are, the better you are.”

What the two communities do share is a history of prejudice in the U.S. — for Asian Americans, the peak came during World War II when more than 112,000 people of Asian descent (two-thirds of whom were U.S. citizens) were forced into Japanese internment camps, because they were perceived as a potential threat during the war. Today, racism against Asian Americans is often brought on by COVID-19, because of the virus’ likely origins in China.

And in the judicial system, they’re battling bias, too. While Asian Americans are the largest minority group represented in U.S. law firms, they’re the least likely group to become partners. Twenty percent of Asian-American lawyers reach that level, compared to 28 percent of Black lawyers, 33 percent of Latino lawyers and 48 percent of white lawyers.

McPike is enthusiastic about bucking that trend. And she’s proud to go against the perceived notion that Asian Americans don’t support their Black brothers and sisters in their current fight for racial equality. She’s a member of the Black Law Student Association at Campbell Law, and she’s a vocal ally, whether it means being active on the social media front or writing letters to her state representatives demanding change.

“I’m not Black, but I see [the systemic racism they face]. And we need to speak up about it,” says McPike, who grew up in New Bern. “In criminal law class — in most of the cases we study — the defendant is almost always a person of color. In property law classes, it’s always about rich white people. I don’t know how you can go through law school and not realize [a history of prejudice in the judicial system] when you’re reading these old cases. You look back and realize that oppression has always been there.”

McPike says her eyes were opened when she got involved in Campbell’s Blanchard Community Law Clinic, which partners with nonprofit agencies to provide solutions for legal problems encountered by clients of those agencies (which include Raleigh-area ministries and rescue missions).

Since its launch in September 2016, the clinic has handled a few hundred cases involving family disputes, domestic violence protection orders, landlord/tenant issues and more. Some of the most prevalent cases are expunctions and drivers license restoration. More than a million people in North Carolina have had their drivers license suspended for failure to appear in court or failure to pay fines. The clinic helps those people get their licenses restored so that they can obtain better jobs and support their families. The legal services are provided by Campbell students, under the supervision of Clinic Director Ashley H. Campbell.

“Working with our students gives me faith in the future of our profession,” Campbell said back in 2018. “Their energy, intelligence and enthusiasm for the law reminds me of how it felt to be a new lawyer.”

“[The clinic] has changed my view even more,” says McPike. “These cases we’re dealing with disproportionately affect minorities. Something as simple as someone losing a driver’s license and not being able to afford getting it back — there are fines that low-income minorities just can’t tackle, and those fines stack up. They can’t drive, and they can’t work. Then it becomes a cycle and it gets even worse.”

The Community Law Clinic is one of several clinics offered by Campbell Law that give students practical, hands-on experiences while also offering valuable services to low-income members of the community.

The Restorative Justice Clinic brings together victims and offenders (often juvenile) to foster collaborative healing. The Senior Law Clinic serves the legal needs of low-income senior citizens in the greater Raleigh area. The Stubbs Bankruptcy Clinic takes on the challenges and difficulties faced by people who need and deserve the protection of federal bankruptcy laws but are unable to afford quality representation. And the Innovate Capital Business Law Clinic works with clients across the area’s entrepreneurial eco system to help them solve real-world business and legal problems.

In addition to an education, these clinics are offering fulfillment to students like McPike, who was working as a technical writer — and doing well in the process — when she decided to go the law school route. At Campbell Law, she says she’s involved and fighting for what she believes in. Her dream is to help launch a social justice clinic, similar to other advocacy clinics in the school.

She’s finding fulfillment at Campbell. And she’s finding her purpose.

“Some day, the media will stop talking about the things that are going on today, and we need to realize that just because it’s not on the news anymore, it doesn’t mean these things aren’t happening,” she says. “That’s why I will continue to be vocal. And I will keep asking people who are white or white passing to check their internal biases. Think about the times you might have shown racial prejudice in the past and maybe didn’t know it. Use these experiences to learn and to make a difference moving forward.”

DARIUS BOXLEY

CARRY THE WEIGHT

At 17, Darius Boxley just wanted something better for himself when he decided to take a law class at his high school. That same year, his older brother was locked up (and he’ll remain so until Darius turns 27); unfortunately far too common for young Black men growing up in York, a city with of one of the highest incarceration rates in Pennsylvania.

Boxley saw law as his exit ramp. He took more pre-law courses as an undergrad at Robert Morris University in Pittsburgh. He enrolled into Campbell Law with hopes of one day representing professional or collegiate athletes or entering a career in sports management.

Big dreams for a kid from a town where “if you’re not an athlete or a musician, you sell drugs.”

“I think often in poorer communities, like the one I’m from, it’s easy to get sucked into a bad lifestyle when nobody has your back,” says Boxley, a third-year student at Campbell Law. “Like my brother … he did something wrong, and for me, nothing about the system seemed unfair at the time. But now I see it differently. He got out last year and now he’s back in. It becomes a cycle for young Black men and women who feel like they have no other out. It’s deep rooted — [those with prior felonies] can’t get a job. They end up in half-way houses and end up doing whatever it takes to just get by. They’re likely always going to be poor. They feel like they’re going to be nothing. They end up breaking the law, sometimes just to provide for their family.”

Boxley says he’s fortunate to have strong support from his family — his father is a pastor, and both parents have been involved in their church his whole life. But he admits there’s pressure on him to succeed. He says there are friends, people from his hometown and other members of his family who see his success as validation that there’s a “way out” of the cycle.

“They’re proud of me, honestly, and they’re rooting for me,” he says. “Some of them joke that they’ll need my services some day. I feel that weight. It motivates me.”

He feels the weight at Campbell Law School as well, where students of color represent a small (but growing) percentage of the student body. When matters of race or social injustice are discussed in class, Boxley says he’s often expected to speak up “on behalf of other people of color.” He felt this way in seventh grade, in high school and at Robert Morris as well.

“It’s just rough that you have to be reminded of your race every day,” says Boxley. “I’m proud to do it, but it’s not a burden for everybody else. White students don’t have to think about it. They’re not constantly being reminded about their race.”

It’s a feeling Evin Grant knows all too well. Grant is a 2016 graduate of Campbell Law who rejoined his alma mater two years later to become director of student life and pro bono opportunities. He was promoted to assistant dean of students this summer, now overseeing more than 30 institutional student groups (including the BLSA) and Campbell’s growing pro bono portfolio.

Grant is just four years removed from sitting in Boxley’s seat — a 27-year-old non-traditional student who was the only person of color in his class at the time.

“There’s a weight that comes with being the only one or one of a few,” Grant says. “Whether you like it or not, you’re the representative. And as you ascend professionally and socioeconomically, it gets even thinner. But you also recognize that you have to be represented; you have to perform at a level and realize that if you fail, anyone who is like me also fails. That’s a weight to carry. Performing isn’t an option; it’s a mandate. You just can’t get by. You have to excel.”

Boxley’s shoulders are strong. He’s an active member of Campbell’s BLSA, having served as community service chair in his second year. He’s proud of the written statement the group released in June calling on students, faculty, the University as a whole and law professionals to initiate conversations and speak out against racial injustice and to fight for improved diversity in law schools and the legal field.

He was recovering from ACL surgery when protests began in downtown Raleigh and was forced to watch from his apartment balcony above where protesters and police eventually clashed. Rubber bullets were being fired yards away from his living room. Tear gas made its way through his windows.

It was a frightening experience, but one that also gives Boxley hope. He views recent protests in the U.S. as necessary and effective. He says the country is listening now.

“I feel like it’s different now,” he says. “People are understanding that we’re sick and tired of being treated this way. Peaceful protests are effective, but the looting and rioting … you can’t blame someone who feels like they have nowhere else to go, nothing else they can do, because they’re sick of being treated in a terrible way. They’re sick and tired of being sick and tired.

“Maybe one day I’ll be successful, but at the end of the day, I still have to go out and be a Black man. At the end of the day, I still face challenges that not everybody faces. Others need to be more sensitive [to the movement], to hear where we’re coming from. They need to understand we live different lives, and we’re fighting for equality.”

MORGAN SWINK

VULNERABLE POPULATIONS

Morgan Swink is a mother of two, juggling raising a newborn and a toddler with the rigors of law school. She thinks about her own mother who was 16 when her father’s imprisonment left her to raise Morgan on her own. Her mother’s struggle motivates her today.

“She had it hard,” says Swink. “She was a teenager and had to quit school to raise me — eventually going back to get her diploma. We were low-income for a while. And on top of that, there were some in her family who didn’t believe people of mixed races should be together.”

That motivation extends beyond simply wanting to be successful. She wants to be there for “vulnerable populations.” She wants to defend young men and women who she feels don’t deserve harsh first-offense sentences. Who don’t deserve to have their life turned upside down because of a mistake early in their life.

“I know my father was a good person,” she says. “I know now in meeting people [incarcerated or facing jail time] that not all criminals are horrible people. And they deserve justice. That’s why I want to focus on juvenile law — people would be surprised how many Black children [who are placed in remedial or special education in school] give up and end up in the prison system. It’s like a pipeline.”

According to the NAACP, one out of every three Black boys born today can expect to be sentenced to prison, compared to one out of six Latino boys and one out of 17 white boys. Five percent of illicit drug users in the U.S. are Black, yet they represent 29 percent of those arrested and 33 percent of those incarcerated for drug offenses. Whites and Blacks statistically use drugs at similar rates, but the imprisonment of African Americans for drug charges is nearly six times higher.

Despite making up close to 5 percent of the global population, the U.S. has nearly 25 percent of the world’s prison population. If Blacks and Latinos were incarcerated at the same rates as Caucasians, prison and jail populations in this country would decline by almost 40 percent.

Black people need better representation, Swink says, and they need more empathetic representation.

And she says the country needs to have real, unbiased, apolitical conversations about police brutality, incarceration rates and the racial makeup of the judicial system before progress can be made. Coming from a mixed-race family, Swink is often stuck in the middle of those conversations.

“When you’re mixed, people with strong opinions don’t always know where you stand,” she says. “One side will point to looting and ask me to defend it. My answer is, ‘Let’s focus on the unjust killing of Black people first.’ I don’t condone the looting and the violence, but I understand where that hurt and violence comes from.”

Swink’s biggest supporter is her mother. When she wasn’t sure about attending law school after having her first child, it was her mother that told her she could do it and pushed her to succeed. When there were times she wanted to quit during her second pregnancy, her mother encouraged her to stick with it.

“My whole family is looking up to me,” she says. “A lot of people are counting on me to succeed. I’m not going to let them down.”

BETTER INCLUSION IN LAW SCHOOLS

Evin Grant was a 2016 graduate of Campbell Law before returning in 2018 to become director of student life and pro bono opportunities. This year, he was promoted to assistant dean of students, and one of his many goals is to make law school more accessible to everybody, regardless of race.

There are several ways to attain this goal, he says. At the micro-level, law schools and universities need policies and procedures in place to give people of color a platform to not only speak, but to feel safe. One recommendation is bringing in someone who specializes in diversity inclusion — someone with expertise who can bring positive change, tout diversity and ensure everybody feels included.

Law schools can also do a better job of painting a clear picture of what a law school education can really do, Grant says.

“Lawyers do more than criminal defense work. If all you know about law is what you see on TV, that’s not clear. Schools can improve on this message. Show what law school offers — show what you can get out of it professionally.”

At the macro-level, Grant says all levels of education need to look inward: “Ask what are we doing that continues to promote historically advantaged populations. People of color have gotten by while not getting help. We got by by assimilating and adapting. Listen to us. And don’t be skeptical when a person of color says, ‘This is my experience.’ It’s easy to write off something that doesn’t happen to you. I can assure you, that thing is real.”

Grant says when a student comes to him and shares their experience, he’s careful not to devalue or diminish that experience because it was just that … their experience.

“We have to let go of our pride and our ego and not devalue lived experiences of other people.”

DIVERSITY AT CAMPBELL LAW

Black students currently make up just over 7 percent of the student body at Campbell Law, and the school ranks near the bottom of national rankings for percentage of minority students (17%), according to online legal research group PublicLegal.

According to Dean J. Rich Leonard, the school is making strides to improve, recruiting more from historically black colleges and creating policies programs to make Campbell Law a “warm, comfortable place for everyone.”

Black students also have a louder voice at Campbell. The school won the Constance Baker Motley National Trial Competition hosted by the National Black Law Students Association in Little Rock, Arkansas, in 2019 — the school’s first national championship in this competition [defeating several HBCUs].

The Campbell Law Black Law Student Association provides support and networking opportunities and each year hosts social events, participates in both regional and national BLSA conferences, and assists admissions with minority recruiting by visiting undergraduate institutions around the state. Faculty and staff also go through implicit bias training — which is mandatory for everybody.

Leonard also touts the school’s annual “racial justice tours,” consisting of 20 students and three professors, that takes them to iconic Civil Rights landmarks throughout the Southeast, from Martin Luther King Jr.’s home in Atlanta, to the Pettus Bridge in Selma and the Legacy Museum in Montgomery.

“Students come to Campbell wanting to be a lawyer with purest of motives,” Leonard says. “They want to make our state and communities a better palce. They’re wide open to any conversation that will broaden their experience and equip them to better deal with society around them.”

STATEMENT FROM CAMPBELL BLSA

“On behalf of the Black Law Students Association at Campbell Law School, thank you to everyone who has taken time to post in support of the pain, justified anger and uncertainty that the Black community is currently facing. We also want to thank Dean Leonard for his continued support of BLSA and Black students at Campbell Law.

“To the Black community, we feel your warranted anger, frustration, disappointment and exhaustion. Society has allowed the systems put in place to protect and serve to continue to disproportionately fail us yet again. The color of our skin has been weaponized against our attempt to exercise our constitutional rights. …

“When peaceful protests are escalated by police actions, kneeling is condemned and a powerful phrase, Black Lives Matter, is mocked, many of us find ourselves struggling to answer, What is the solution? …

“We are all on the path to enter into a profession represented by Lady Justice. Her blindfold and set of scales symbolize that the ultimate goal is for justice to be blind and apply equally to all. It is clear that the criminal justice system and society as a whole have fallen short of this goal.

“We as a community have the power to make changes to the systems perpetuating discrimination, racism and the unjust treatment of members of the Black community.

“To professors, we charge you to initiate conversations regarding the underlying racial contexts of the cases and opinions read in class.

“To students, we charge you to use your voice in and out of the classroom. …

“To the University, impose inclusion training sessions for administrators and students to ensure cultural sensitivity.

While a societal shift will not happen overnight, we can all utilize our platforms to begin creating a better community for generations to come.”