Jim and Gaylord Perry’s ties to the moon landing 50 years ago go beyond their memorable days on the baseball diamond

By Billy Liggett

Daphne Perry knew an opportunity when she saw one. And this opportunity was just too good to pass up.

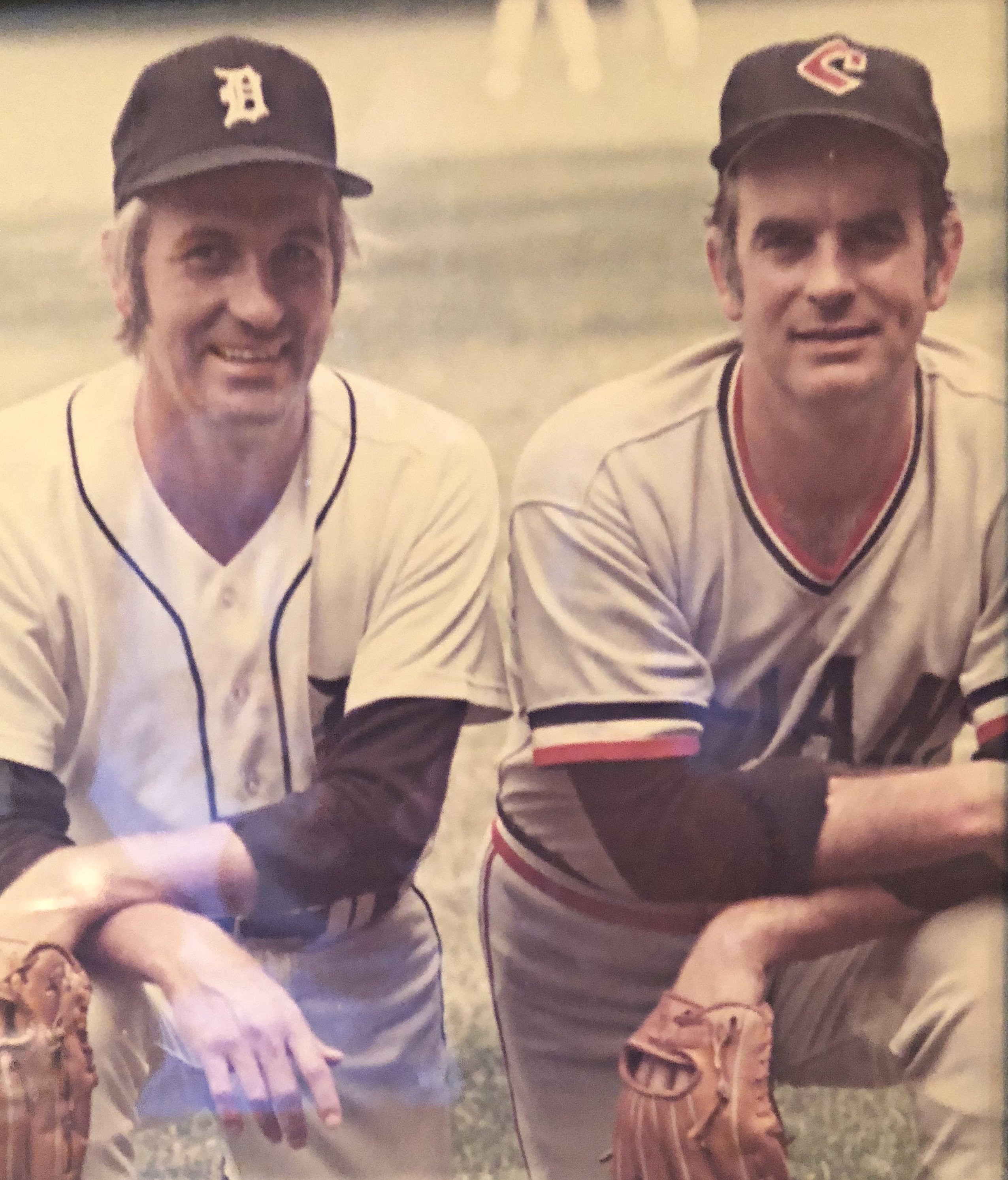

There in the same reception hall in Upper Sandusky, Ohio, on Aug. 17, 1985, were the Perry brothers — Jim and Gaylord, Campbell College teammates who’d go on to become winners of a combined 529 Major League baseball games and three Cy Young awards — and the First Man himself, Neil Armstrong. The occasion was the wedding of Jim and Daphne’s son, Chris (who’d go on to become a PGA golf pro) to Katharine Solacoff, daughter of Armstrong’s childhood friend Konstantine “Kotcho” Solacoff.

“Chris had always wanted his dad to tell Mr. Armstrong his own moon story,” Daphne says, referring to July 20, 1969 — the “one small step” that turns 50 this weekend. “We knew he hadn’t heard it. And this was his chance.”

It’s one of the better stories in a sport full of improbable legends, feats and coincidences. And it starts seven years earlier in 1962 — months before John F. Kennedy famously declared there would be a man on the moon by the end of that decade.

According to baseball lore, Gaylord was taking batting practice when the aptly named San Francisco Chronicle sportswriter Harry Jupiter noticed the rookie pitcher’s hard swing and suggested to Giants manager Alvin Dark, “This Perry kid’s going to hit some home runs for you.” Dark turned to Jupiter — as Perry tells it in a July 13, 2009 issue of Sports Illustrated — and replied, “There’ll be a man on the moon before Gaylord Perry hits a home run.”

Dark’s prediction would hold true over the next seven years. While Gaylord would win more than 80 games and become an All Star in his first seven and a half years on the mound, his hitting was about what you’d expect from a pitcher. His batting average by the late 60s hovered in the low .100s, and a career of nearly 500 at-bats had no home runs and only 13 total RBI to show for it.

Gaylord brought an 11-7 record into his start against the Los Angeles Dodgers and starter Claude Osteen on July 20, 1969. More than 32,000 fans showed up for the 1 p.m. matinee.

Seven minutes after Gaylord’s first pitch, Neil Armstrong and Buzz Aldrin landed on the lunar surface.

Approximately 25 minutes later, Gaylord stepped to the plate against Osteen and drilled a shot to centerfield that, to his amazement, cleared the wall. It was his first, and one of only six he’d hit in his 22-year Hall of Fame career.

He also pitched a heck of a game that day, too — going all nine innings and striking out six Dodgers in the Giants’ 7-3 win. But it was his “Moon Shot” that the Perry family will always remember.

One sportswriter quipped in the following day’s paper: “The way Gaylord Perry swings a bat, he stands as much chance of hitting a home run as … oh … as a man does of walking on the moon. Well, Perry and astronauts Neil Armstrong and Edwin Aldrin made it together Sunday.”

The night before his brother sent a pitch into orbit, Jim Perry was enjoying a rare nice dinner with Daphne 807 miles away at Seattle’s most recognizable landmark.

You guessed it … the Space Needle.

Jim was scheduled to pitch for the Minnesota Twins that Sunday against the expansion Seattle Pilots at Sick’s Stadium, a tiny temporary home for a team that would go bankrupt at season’s end and become the Milwaukee Brewers the following year. As was customary under Manager Billy Martin, Jim was allowed to leave Saturday’s game early to enjoy a nice meal with his wife and get well rested for the following day.

“I had a radio with me,” Jim recalls, a note that’s met with an eye roll from his wife, “because I wanted to know what was going on. The reception on top of the Space Needle wasn’t the best, so I kept having to walk over to the other side to hear the game.”

It turned out to be a smart move. After nine innings, the Twins and Pilots were tied, 6-6. By the time the game got to the 12th, Jim told Daphne he probably needed to head back to the stadium in case Martin needed more pitchers. Both teams would score a run in the 15th inning, and Jim was back with his team as an emergency pitcher. Play was suspended in the top of the 17th — the scored tied 7-7 — because of Seattle’s 2 a.m. curfew. The league ruled the teams would restart the 17th inning on Sunday, then play that afternoon’s regularly scheduled game after Saturday’s winner was decided.

Jim knew what that meant for him before Martin even told him.

“I knew I’d have to finish that game and start the next one,” he says. “And sure enough, Billy Martin tells me, ‘Don’t worry, we’ll win that one in two innings, and you just go as long as you can on the next one. We’ll find you some help.”

Jim would retire the first three batters he faced that afternoon before starting the top of the 18th off with his own plate magic — a double that would eventually make him the game-winning run (the Twins actually scored four to take an 11-7 win). His teammates would retire to the clubhouse in between games to crowd around a few small black-and-white televisions and watch Apollo 11 make its landing.

Jim, however, stayed on the field and threw to keep his arm warm.

“I could hear people hollering and cheering from the locker room,” he says, “but I had to stay loose. I had to get ready for another game.”

In true workhorse fashion, Jim Perry didn’t need help in the nightcap. He pitched all nine innings of shutout baseball — got another hit and scored another run — in a 4-0 Twins win.

The final line for the Perry brothers that night:

On the mound: 21 IP, 3 ER, 11 K and 3 W’s

At the plate: 7 AB, 3 H, 2B, HR, RBI

Jim Perry remembers receiving the news that evening that his brother hit his first Major League home run. The news made him smile.

“I thought it was great,” he says. “He always swung the bat hard; he just rarely ever made contact. But you didn’t have to be a great hitter with Willie Mays, Willie McCovey and Bobby Bonds in your lineup.”

Back to Aug. 17, 1985 — the wedding, the reception and Daphne’s one chance at getting the Perry brothers to share their story with the great Neil Armstrong.

So at the rehearsal dinner, Jim told Armstrong that on July 20, 1969, he and Gaylord “had a pretty big day, too.”

“I think he enjoyed it,” Jim says. “I mean, it wasn’t landing on the moon. But it was a great story.”

But the Perrys’ connection with the moon landing goes beyond their dual efforts on their respective diamonds 50 years ago and even beyond that wedding ceremony in 1985.

In his authorized biography, First Man: The Life of Neil A. Armstrong, published in 2005 (seven years before his death), Armstrong told the story of visiting his childhood friend Kotcho at the home of Chris and Katharine Perry in Ohio in the early 2000s. He recalled the youngest of the Perrys’ children — Jim and Daphne’s granddaughter Emily — taking him by the hand “on an expedition through her house.”

“I want to show you a secret, but don’t tell anyone,” 5-year-old Emily told Armstrong. “This is a secret which no one knows about.”

Up in the attic of her home, Emily showed Armstrong a giant dead bug and whispered again that it was a secret. She then led him to her room, where she showed the legendary astronaut her lamp, her mirror and some of her books.

“This one is on Winnie the Pooh,” she told him. “And this one is about Sleeping Beauty, and this is Cinderella, and, oh, here is a book about Neil Armstrong. He was the first man on the moon.”

The book concludes: “Then she stopped, hesitated for a moment, looked at the nice older man who had come to visit her in her house, and said, ‘Oh! Your name is Neil Armstrong, too, isn’t it?’”