Red McDaniel was brutally tortured as a POW in Vietnam, but survived six years in captivity thanks to his faith and his family. Over 40 years later, he’s still fighting for his co-pilot and the men still listed as Missing In Action.

I’m intimidated at the thought of interviewing Red McDaniel. And the five-hour drive from Buies Creek to his home in Alexandria, Virginia, on a particularly hazy, humid early August morning isn’t doing much to calm my nerves. In fact, it’s only giving me more time to question my questions.

What do you ask a man who spent nearly six years in a North Vietnamese prison; three of those years on the receiving end of some of the most brutal torture ever described [by someone who survived it]? How do you even pretend to understand? What if I ask the wrong thing?

I came across the compelling story of Capt. Eugene “Red” McDaniel by accident about a month earlier. Searching for information on Campbell’s football program before it began its 56-year hiatus in 1950, I found his name on a list of Campbell Athletics Hall of Famers. The big capitalized letters “POW” stuck out to me, and I had to learn more.

And, boy, was there more to learn.

I read all 192 pages of his 1975 autobiography, Scars & Stripes, almost in one sitting. I moved on to a short documentary he appears in called “The Spy in the Hanoi Hilton.” I watched all 17-plus hours of Ken Burns’ recent documentary, “The Vietnam War.”

I wanted to learn as much as I could about this man — now 86 years old — and the war he fought in before I wasted a single, valuable minute of his time. I rarely ever feel this way about the men or women I’ve interviewed over the years — that I might be wasting their time.

I arrive at his modest two-story home — a stone’s throw from George Washington’s Mount Vernon in Alexandria — just after lunch. I’m met at the door by the man himself — still very much recognizable as the young, handsome fighter pilot from the countless photos I’ve seen taken 45 and 50 years earlier … before and after “the experience.”

Do I call it “the experience?”

To break the ice, I hand him an Elon University alumni magazine that was sitting in his mailbox by the door. McDaniel attended and graduated from the rival school after his two years at the then-Campbell Junior College.

“Looks like they beat me to it,” I joke, handing him the magazine. This gets a laugh as we’re immediately joined by his wife, Dorothy (whose 1991 book, After the Hero’s Welcome, is equally fascinating) and the couple’s oldest son, Michael, who handles media requests for his parents and made today’s meeting possible.

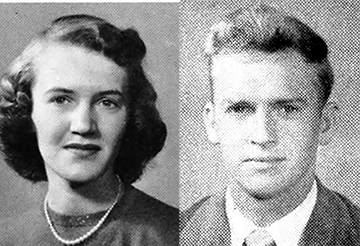

I’m invited to sit in the living room on a couch that I swear my grandmother also owned during my youth. I begin with the small talk — his Campbell experience. How he met Dorothy on his first day in Buies Creek and how they knew they were meant for each other. Theirs is a great story. And I’m all too happy to tell it.

But my mind is elsewhere. I want to ask about Vietnam. Ten minutes into our conversation, there’s a pause, marking the end of their “how we met” and “why I joined the Navy” tale. I see my opportunity.

“When was the first time you’d ever even heard of Vietnam?”

I’ve prepared for these next two hours. The intimidation has become excitement. Few people get a front row seat to hear a story like this. I only hope I can do it justice.

There is no feeling quite like knowing you are in a strange country, surrounded by a people who know no rule but death to the enemy. On top of that, of course, is the jungle. There is nothing compared to tropical jungle when it comes to survival. It is thick, thorny, full of unexpected dangers, ruthlessly hot and defiant of man. … A man is soon aware of its immensity, its gigantic suffocating encirclement, its relentless squeeze on life systems that depend on air, good water and food.

— Capt. Red McDaniel, Scars & Stripes —

Red McDaniel had flown more than 80 missions with his bombardier and navigator, Lt. James Kelly Patterson, when he was called to fly his 81st mission from the carrier Enterprise on May 17, 1966. This was to be another Alpha Strike, the bombing of a “high-value target” from his A-6 fighter jet — part of Operation Rolling Thunder, intended to pressure North Vietnam’s communist leaders and weaken their ability to wage war against the U.S.-supported South Vietnamese.

He shaved that morning, remembering not to apply after-shave lotion or deodorant (these were luxuries in Vietnam, and the slightest hint of these smells could give him away if he was shot down).

“But, even as I finished shaving, I did not consider being shot down and taken prisoner,” McDaniel wrote in his book, Scars & Stripes. “The chances of being killed were more real, and for this I had to prepare my mind every morning.”

McDaniel had never even heard of Vietnam a decade earlier when he joined the Navy after graduating from Elon. Baseball might have been the better option, as he hit nearly .400 during his time at Campbell and Elon, but McDaniel was already in his mid-20s and felt “too old” to climb through Minor League farm systems for a crack at the big leagues. He chose flight school in the Navy because, like sports, it presented a challenge. Flying the A-6 off of aircraft carriers was considered “elite,” he says, and he wanted to be the best.

He was deployed to South Vietnam in November 1966 — by that time, the number of U.S. military personnel there had grown from 184,000 at the beginning of the year to nearly 400,000 by year’s end. Neither Red nor Dorothy would have guessed the war would last another six years.

“It was just a war, you know? And that’s what Red was trained to do,” says Dorothy, who wrote in her book, After the Hero’s Welcome, that their “good bye” involved — much to her surprise — a reminder from Red to sign Michael up for Little League in the spring.

Michael remembers his good bye vividly. He was 8 at the time, and he carried a small reel-to-reel tape player with him and recorded his dad’s words before he left.

“I don’t know why I did that,” he says. “I just remember at the time wanting to capture it, knowing he was going to be gone for a while. The last thing he told me was to take care of mom while he was gone.”

A big mistake, Red adds with a laugh. “I guess I didn’t think I’d be gone that long.”

About 60 miles inland on that fateful morning in May, McDaniel and Patterson began seeing surface-to-air missiles coming up “like telephone poles with fins on one end.” The fifth missile exploded between their jet and another, and the shrapnel took out their A-6’s hydraulic systems. The jet began to nosedive toward the North Vietnamese hills. At 2,000 feet above a 3,000-foot mountain range, Patterson ejected first. Moments later, McDaniel shot out of the cockpit. The two parachuted in different directions from the eventual crash.

“I remember floating down,” McDaniel says, “and thinking how relieved I was that I wouldn’t have to fly any more missions. I remember very vividly landing in a tree, then falling 40 feet from that tree and crushing a vertebrae when I landed.”

The pain was immense, but McDaniel was able to radio to the other pilots on the mission that he had survived the crash. He ditched his parachute and strapped on a survival pack — his goal was to march up to the top of the hill so he could be spotted by rescue helicopters that would surely be searching for him over the next 24 hours. His other goal was to avoid capture.

At 10 that night, McDaniel saw a propeller aircraft fly overhead with its lights on. He tried to radio, but there was no response. He fell asleep that night on a tree trunk and woke up the next morning to continue his trek toward rescue (constantly pulling leeches off his skin as he walked). He saw two jets fly by that morning, the pilot of one radioing in to say the “jolly green giants” (helicopters) would arrive in 45 minutes.

Seven hours later, McDaniel still waited.

At 1 p.m., a bullet flew by his head. He turned around to see two Vietnamese men aiming at him from 25 yards away. Within a minute, about 15 men joined them.

“They had a mangy dog with them,” he wrote in Scars & Stripes. “They were all barefooted, except for a couple who wore sandals made out of a rubber tire. I noticed their feet were bleeding, which meant they had been moving around all night looking for me; that explained the sounds I had heard in the night and this morning. So now I simply stood there staring back at them, conscious of how little they seemed in their floppy, pajamalike clothes, not sure of themselves even now that they had me. This was ‘the enemy,’ I thought, but looking at them, all I could think was that they appeared to be more like a bunch of kids out in the jungle looking for something to do.”

Two thoughts ran through McDaniel’s mind: “Where is the Air Force?” and “God, where are you?”

That evening, roughly 8,300 miles away, Dorothy McDaniel received a visit at her Virginia Beach home from an officer dressed in all white. “Red’s down,” was all the man, accompanied by a chaplain, could say.

That night, Dorothy told her three children — Michael, 8, David, 6, and Leslie, 4. Michael received the news first after a family friend had taken him to the ice cream shop. He got home that evening with a big wad of bubble gum crammed into his mouth, he recalls.

“Mom meets me at the door and says, ‘Let’s go back to your room and talk,” he says. “She sits me on the bed and says, ‘Let me hold your bubble gum. What I’m going to tell you might make you cry.’”

It’s at this point in his book — between falling from that tree and being captured — that McDaniel takes a few pages to backpedal and tell the story of how he met Dorothy Howard on his first night at Campbell College in 1950.

It’s a strategic placement by the editor and it’s a story that is vital throughout the six years of his imprisonment. Meeting Dorothy marked his true introduction to Christianity. And it was faith that held Red McDaniel together as he endured and withstood brutal torture and — even worse to him — the uncertainty of what tomorrow would bring.

I tell Red and Dorothy from the beginning that I’m going to ask a lot of Campbell questions. I’m probably the 2,000th person to interview them about their shared POW experience. Campbell, however, is unique to today’s talk.

McDaniel tells me that on his first day of school in Buies Creek, he filled out a form at registration and paused at a question you don’t see at too many colleges today: Are you a Christian?

“I didn’t know how to answer that,” McDaniel wrote then, and shares again now. “I believed in God and Christ, but I wasn’t sure what I had that would qualify me for the title. But I put ‘yes’ down anyway; after all, I was at Campbell for athletics, not religion. So it really didn’t count in the end. But I knew, deep down, that it did.”

That same night, he met Dorothy Howard, the daughter of beloved professor Charles Howard, who had lost both of his parents, two brothers and a sister to tuberculosis when he was younger, and was raised by his grandparents. He served as a pastor for 26 different congregations in North Carolina and preached more than 25,000 sermons in 23 states. He succeeded University founder J.A. Campbell as pastor of Buies Creek First Baptist Church when Campbell died in 1934, and four years later, became Campbell College’s first religion professor.

Dorothy, her husband recalls, had a “grace and poise about her that made me want to be around her,” and her family’s faith in Christ had an impact on him. He realized faith required much more than belief.

That faith was first challenged when the green helicopters never showed up for McDaniel and his navigator. Back home, Dr. Howard also struggled.

“My grandfather thought that if you got on your knees and prayed hard enough, God would perform miracles,” Mike McDaniel says. “And that never happened … which was hard for him to accept.”

Dorothy McDaniel woke up from a deep sleep on the night she learned her husband had been shot down. Unsure whether he was captured or killed after his last radio transmission, she instinctively reached for her Bible on the nightstand and opened it. The pages flipped directly and unintentionally to Psalm 91 — a passage she says she clung onto for years.

You will not fear the terror of night, nor the arrow that flies by day, nor the pestilence that stalks in the darkness, nor the plague that destroys at midday.

A thousand may fall at your side, ten thousand at your right hand, but it will not come near you.

No harm will overtake you, no disaster will come near your tent.

For he will command his angels concerning you to guard you in all your ways;

They will lift you up in their hands, so that you will not strike your foot against a stone.

You will tread on the lion and the cobra; you will trample the great lion and the serpent.

“Because he loves me,” says the Lord, “I will rescue him; I will protect him, for he acknowledges my name.”

I know what’s coming next in the story. I read about the beatings McDaniel endured — the most notorious a weeklong torture session after an attempted escape by other soldiers. It’s this story that most remember about his POW experience. But I’m also stunned by other details of his imprisonment — the rat-infested cells, the inability to communicate with his family that he was alive, the lack of food and basic medical care.

And I’m watching McDaniel recall these memories without the slightest trace of stress, without a single wince. Later on, I ask him if the torture changed him. If it affected his marriage or even his sleep. His answer surprises me.

“In my 46 years back, I’ve only awoken one time with a bad dream that I was still in prison. One time. That’s amazing,” he says, punctuated like a true pride point. “For our last three years, there was no torture. I think those three years gave me time to realize there was still value in my life. Those three years allowed me to put [the torture] behind me.”

His son adds: “I remember vividly the Navy psychologist sitting us children down and telling us that dad had a rough-go and that he didn’t know what condition he’d be in when he got home. That scared the daylights out of me. We didn’t know what to expect.

“But we didn’t see any of that,” he says, looking over at his dad. “Not once.”

I was beaten regularly by a two-man relay team with more than 120 licks with that fan belt. By now, I was passing blood … and that meant there were internal injuries. My eardrum ruptured when they struck me across the head with my own shoe, and it too was oozing blood. They continued to beat me that way until I thought I would go out of my mind with the pain. I said, “Okay, I’ll tell you, stop.” And they stopped. I took a few minutes while they waited just to get my breath and allow the pain to dissipate a little, and then I said, “I don’t have any answer.” So back to the beating.

— Capt. Red McDaniel, Scars & Stripes —

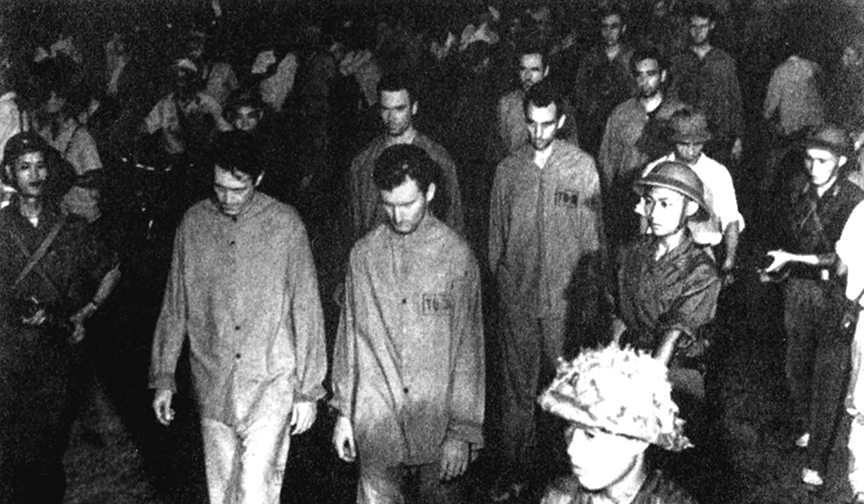

A day after his capture, Red McDaniel was hauled off to the infamous American prison camp in Hanoi — dubbed the “Hanoi Hilton” — at 5:30 in the morning. He rode in the back of a small pick-up truck next to a 50-gallon drum of gasoline that spilled on him with every bump. The trip was excruciating, as McDaniel had yet to be treated for a cracked vertebrae and other broken bones resulting from the ejection from his A-6.

He was tossed into a cockroach-infested cell and interrogated immediately upon his arrival. “You talk. Medicine later,” they told him. When he refused to give nothing more than his name, rank and serial number, he was tied up with ropes and bound so that his arms stretched behind his back and his shoulders were ready to pop out of their sockets.

“I pretended to pass out several times in hopes they would untie me and leave me alone,” McDaniel wrote of his first day as a prisoner of war. “But they were wise to that. At times, I would bite my shoulder hard to try to transfer the pain from one area to another. Then I began pounding my head against the wall, hoping for blood, something liquid to ease my terrible thirst.”

He was fed watery soup with leafy greens in it — just enough to keep him alive — those first five days. In between meals, the interrogations returned. Questions about the Navy’s new walleye missile, new targets in Hanoi and something called the “television bomb.” To satisfy his captors, McDaniel began talking … not about his A-6 or other valuable information, but instead false information about A-1 jets and targets in the Demilitarized Zone. After the fifth day, he was taken to a wash area (to sleep, not to wash) and released from his leg irons.

“Eight hours later, I was put into solitary confinement,” he wrote, “and I began to get some sense of the horror that was ahead of me now. … I knew I was up against a monstrous situation, against an enemy who seemed to take great satisfaction in inflicting pain, who performed like robots in doing so.”

McDaniel had little communication with the other pilots imprisoned at his camp, and it was weeks before he was able to talk to an American — he asked McDaniel if he knew “the code.”

“Morse code?” McDaniel asked. “No,” he replied, “the camp code.”

Many of the pilots in Hanoi had been trained in a code system — a series of knocks or taps that could line up right and down with a five-column grid of letters to spell out words. One knock followed by a pause and one other knock made an “A.” One knock followed by two knocks was a “B.” He titled Chapter 4 of his book, “Communicate or Die” — “Men faced with the hopelessness of a military prison and the uncertainty of what a day might bring from the enemy … soon become desperate to communicate with others. Morale was essential, and one of the keys to morale was to beat the enemy as often as possible in their attempts to keep us isolated.”

McDaniel and his fellow prisoners knocked on walls, water pipes and floors. They wrote notes using cigarette papers and toilet paper, their ink made from ashes and water. They crawled through ceiling vents for short visits to other rooms. The communication was important because it meant they weren’t alone. It symbolized camaraderie in the worst of environments.

“It gave me a purpose,” McDaniel says from his chair at home. “I go back to high school and college and remember how aggressive I was in athletics. The thought that you play to win. But I was also the biggest optimist in Hanoi. When guys would tap down to my cell and ask me when they’re going home, I always answered, ‘Two months.’ After six years of that, I lost a lot of credibility … but, you know, that’s what they wanted to hear. That was my livelihood to truly believe that answer. The one thing they could not take was my faith.”

Three years into McDaniel’s imprisonment, two Americans broke out of the Hanoi Hilton. McDaniel was unaware of their plans, but the prison communication system soon relayed the message to him that they had escaped. Both men were recaptured; one of them died during the torture that followed.

A month later, on June 14, 1969, North Vietnamese officers came for McDaniel and his cellmates, Al Runyan and Major Ken Fleener, to question them about their knowledge of the escape attempt. When McDaniel told the officers he had no knowledge of the attempt, his pants were pulled down, and the officers took turns hitting him in the rear with a rubber fan belt. He was then forced to kneel and keep his hands above his head (wrists locked in irons). When his arms finally fell after an hour on his knees, a guard hit him hard across the back of his head. When he could no longer hold his arms up, the guards tied them and kept them above his head with rope. McDaniel spent that night sitting on a stool. He was beaten with a rubber sandal across the face if he spoke or asked questions.

That was Saturday. On Sunday, much of the same — fan belt beatings, arms up and spending the night sitting on a stool. By Tuesday, McDaniel’s knees were infected from kneeling on the concrete floor. The guards continued to beat him — this time with bamboo sticks — if his arms dropped below his head. Halfway through the week, McDaniel confessed that his room was the source of the escape plans. It wasn’t. The confession bought him an hour of relief, until the officers figured out it was a lie.

The torture continued, and on the fifth night of beatings and no sleep, McDaniel became sick from the infections — his fever at 104 degrees. “So much came out of those wounds that whenever I moved around in that small room, a trail of pus would be left behind along the floor.”

The torture reached its peak on the sixth night. McDaniel wrote in his book that he became irrational and grabbed a guard and began yelling at him. The commotion attracted other guards to the interrogation room, where they tied McDaniel’s arms again with ropes and this time pulled him up from the ceiling about two feet off the ground. At one point, his arm snapped in two.

“You’ve broken my arm,” McDaniel yelled at the officers. “No,” one replied. “We have not broken your arm. You have broken your arm.”

The next day, the guards tied damp cloths around his arms and around cords hooked up to a battery. The electric shock treatments went throughout the day. McDaniel recalled the pain as “blinding, but mercifully I was so tired that it was only another blurring dimension of the pain I already had.”

The final beatings came on Friday — 120 licks with a fan belt, passing blood in his urine, ruptured eardrum. When McDaniel couldn’t take it any longer, he told the officers what they wanted to hear. But none of the names he gave were part of any escape committee. None of the information he gave was true.

But the torture ceased. At least for now. After a week of brutality few men could endure, McDaniel looked to God. And he thanked him.

“That Friday night, I slept for the first time in a week. I was mistaken to think the interrogations were over or even the torture. But as I slept, it was a sleep of assurance — God was not far outside this hell. If I had to go on with this nightmare, then I was sure He was with me. Nothing else mattered.”

I interviewed Red McDaniel nine days before the passing of Arizona Sen. John McCain. Knowing the senator — the most famous of the North Vietnamese prisoners after his A-4E Skyhawk was shot down over Hanoi in October 1967 (a year and a half after McDaniel’s arrival) — was close to death after a lengthy fight with brain cancer, I asked McDaniel about their relationship. About his thoughts on the final chapter of McCain’s life.

“Oh boy,” his son, Mike, says through a winced smile. “If you want to get him talking for 20 straight hours, get him talking about that.”

I knew there was bad blood between McDaniel and McCain before asking the question (articles have been written about their disagreements following the war). I struggled with whether I was going to bring it up. That’s not what this story is about, I told myself.

But it’s timely. And it’s important.

“You need to hear this,” the captain says to me. His tone is stern, more so than when he recalled his weeklong torture following the escape attempt. “It may not be part of your story, but you need to hear this.”

And so I listen.

McDaniel was looking out of his cell on Oct. 26, 1967, when he heard an explosion and saw a man floating down by parachute toward Truc Bach Lake outside of Hanoi. John McCain — the son of well-known Admiral John S. McCain — landed in the lake and nearly drowned before being pulled ashore by North Vietnamese villagers, who crushed his shoulder with the butt of a rifle and bayoneted him in the groin area. He spent six weeks in a hospital after the Vietnamese discovered his lineage, and McCain’s status as a prisoner of war became national news. In March 1968, McCain was placed into solitary confinement — that same year, he refused to be released unless all prisoners who were captured before him were released first. He remained in solitary for two years.

You’ve almost certainly heard this story.

The bitterness between McDaniel and McCain developed years later during McCain’s involvement — along with Sen. John Kerry — in the U.S. Senate Select Committee on POW/MIA Affairs in the early 1990s. The committee found “no compelling evidence that any American remains alive in captivity in Southeast Asia.”

It’s a finding that McDaniel says he will never accept.

McDaniel knows his bombadier Patterson ejected safely from their A-6 on May 19, 1967. He knows Patterson was able to establish radio contact with other aircraft in the area for four days. He knows that on May 21, Patterson reported that enemy forces had taken a recovery kit that had been dropped for him.

Beyond that, nothing is certain. When McDaniel was released in 1973, he assumed Patterson had died. When he began to serve the Navy as a liaison to Congress, he says he began to see evidence that Americans were still alive in Southeast Asia. He was told in 1986 that men with Patterson’s knowledge of A-6 technology were dubbed “MBs” in the intelligence community — “Moscow Bound.”

McDaniel believes, without a doubt, his friend wound up in Russia (there have been testimonies and reports written since, both corroborating and conflicting with this claim).

McDaniel has no idea if Patterson is alive today — he would be 78 years old — but the thought that he was possibly left behind was and is today a soul-crushing revelation. Since his return, McDaniel has been a vocal advocate of the national POW/MIA movement, whose advocates believe several U.S. soldiers and airmen were kept alive by Communist forces after the U.S.’ involvement in the war ended in 1973 and that the U.S. government has covered up their existence ever since.

Dorothy McDaniel’s book, After the Hero’s Welcome, goes into her husband’s work and advocacy in Washington, D.C., in great detail. She writes about the toll her husband’s fight with those who “closed the book” on searching for living POWs had on him and his trust in his government.

“I had prayed that Red’s disillusionment with the high-ranking [U.S.] officials … wouldn’t do him in, leaving him bitter and despairing,” she wrote. “The Vietnamese had not been able to break his spirit. The ultimate tragedy would be for his own countrymen to do what his enemy in Vietnam could not.”

I tell the McDaniels this is all fascinating, but I attempt to assure them this is supposed to be a story of courage and faith and family and resilience.

I’m not looking cover ups or conspiracies.

But I also see this hurts McDaniel more than any torture session he endured.

McDaniel talks about his torture in Vietnam like he’s recalling a bad vacation. The descriptions are brutal, but he’s mostly emotionless in telling the story. Throughout the nearly four-hour interview in his home, his emotions only really come alive when he’s talking about Patterson and his fight for the truth. It’s a topic he brings up multiple times on this day, even after questions that are clearly attempting to steer the other way.

“I’ve come to the conclusion that it’ll take divine intervention [for the truth to come out],” McDaniel relents. “Somehow, God will let it out. Maybe not in my lifetime.”

Before I boarded the plane, I turned and looked at Spot, the camp commander who was now officially releasing us to our country. I remember all those threats in prison: “You will never go home! You will be forty years old before you get home!” But looking at Spot now, I did not feel like gloating. For me, it was going home to a new life, to loved ones. What was it for him? I didn’t know. Looking at him now, I did not think of the many hours of interrogation under him, the torture, the harassment. He was just another man in another part of the world who had done his job. … I did not see him as an animal, void of emotion. I saw him now as just a human being, and somehow I wished we could all sit down there on that tarmac and talk over what life is all about — what it could mean, free of bars and cells and all of the strange, terrifying things that go into political doctrines that separate us.

— Capt. Red McDaniel, Scars & Stripes —

The letter arrived at the McDaniel home the same day as a solar eclipse — March 7, 1970. Dorothy McDaniel remembers this because that letter shared front page news with the natural phenomenon in the next day’s Virginian Pilot newspaper.

Dear Dorothy, Michael, David, Leslie:

My health is good in all respects — no permanent injuries. You are my inspiration. Children, work, study, play hard, help each other and Mommy be strong for our reunion. Invest savings in mutual funds and stock. Your decisions are mine. Dorothy, I love you deeply.

Eugene

15 December 1969

He survived.

Three years and 10 months after the McDaniel family learned their husband and father was shot down and captured in North Vietnam, they finally had proof he was alive. They believed it the whole time — until news comes otherwise, there’s always hope — but they never had the proof, despite countless hours sifting through photos and videos (“propaganda”) the Vietnamese had released over that time period. Despite numerous attempts to write Red and force the Vietnamese government to release the names of their captured soldiers.

But now they knew. “All the hard work, the grueling, emotionally-draining speech-making and public appearances had finally resulted in a six-line letter from Red,” Dorothy wrote in her book. “He was alive! He was alive, and the North Vietnamese had admitted he was alive. To me, that meant they couldn’t let him die.”

Dorothy had become a public face (one of several) for all POW/MIA wives during the Vietnam War. She was one of the founders of the National League of Families of Prisoners and Missing in Southeast Asia, and she served as the state coordinator for POW/MIA families in Virginia. She appeared on television, was interviewed for countless newspaper articles and in November 1968, she made the first of several speeches to help focus public attention on the hundreds of men held captive in Southeast Asia (she thought her first speech would be in front of a small group of “church ladies” … it turned out to be a huge group that filled a fellowship hall).

And she was and is certain that her refusal to follow the government’s suggested “keep silent rule” by speaking out and sending letter after letter to her husband’s captors led them to finally allowing McDaniel to write that first letter in 1969. She was convinced the North Vietnamese government would respond to public opinion — they regularly allowed hand-picked reporters into Hanoi to write fluff pieces on the “humane treatment” the prisoners were receiving.

“The decision to go public with my personal story — to expose my family to public scrutiny — was [scary],” she wrote in her book. “But how do I sit back and not try? I believed that Red’s life was on the line.”

The public’s watching eye did make a difference. While Red McDaniel slowly recovered from the weeklong torture and beating he endured in the summer of 1969, word began coming in from new prisoners that POW wives back in the United States were persistent in their efforts to demand better treatment of their husbands. In October of that year, the prisoners began receiving better food.

“Now they gave us bread most of the time with our soup,” McDaniel wrote in his book. “We were getting canned meat at times. Sometimes candy. Food packages were finally coming through, and now the Vietnamese were not holding them back so much.”

In December that year, McDaniel wrote his first letter home. Also that month, the guards allowed the prisoners to attend a Christmas church service (even though the North Vietnamese “preacher” spoke of U.S. imperialism and warmongering, McDaniel says it was still nice to sit among his fellow prisoners).

It was still prison. And it was by no means comfortable. But McDaniel’s final three years in North Vietnam did not include torture. He was never again beaten. He says those final three years are the reason he was able to write Scars & Stripes in 1975, just two years after his return. He was able to put the nightmare behind him and focus on his faith and his future.

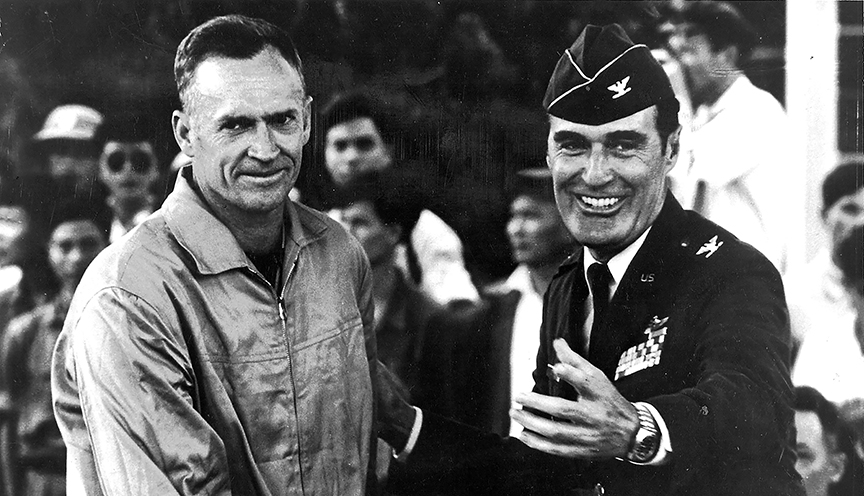

Red McDaniel and nearly 600 other POWs were released from captivity on March 4, 1973. McDaniel, who shed few tears in Hanoi except for his lowest moments, says the tears came easily at the sight of a C-141 aircraft that awaited him on a North Vietnamese runway that day. “Even as God had stayed at my side through all that time and taught me things that were to change my life completely about His reality and His presence in suffering, somehow that American plane socked home some of the things that made America and God great,” he wrote.

McDaniel and the now-former POWs came home to a hero’s welcome — a far cry from the reception many Vietnam vets received during and after the war. He had heard much about the protests and division back home (the Vietnamese were happy to share that news), but he saw little to none of that. Part of it was because the public had genuine sympathy for their experience. Part of it was because he lived in Virginia — a much more military-friendly state than other areas.

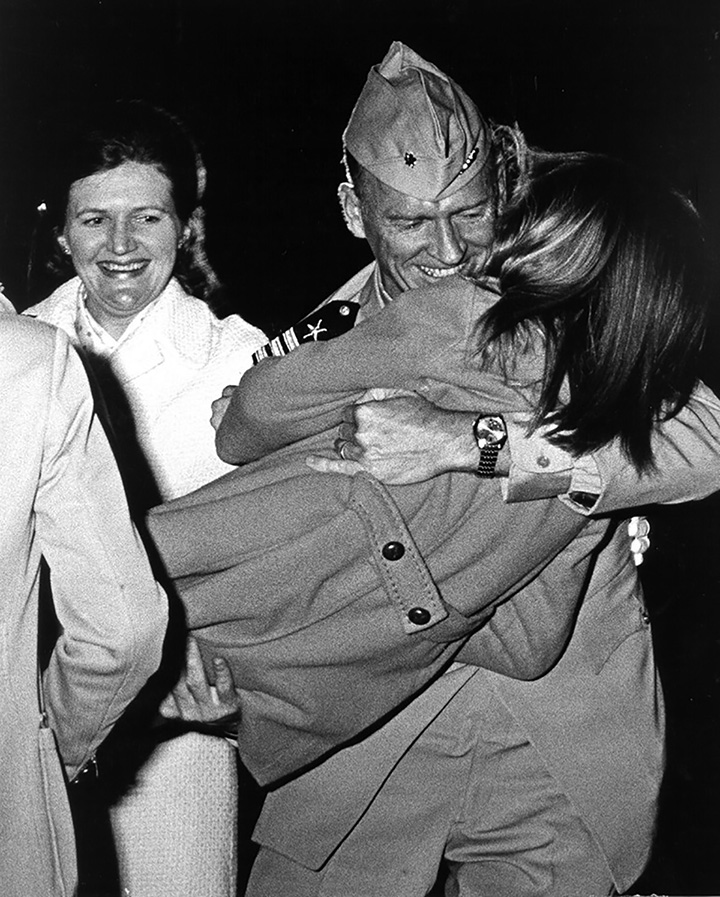

Three days after leaving Vietnam, McDaniel was reunited with his family. “For how many nights had I visualized this moment?” Red wrote. “For how many nights, throwing that little ball of bandages up and down in my cell, did I see this scene, live it over and over in anticipation? And now there it was.”

Mike had grown considerably. He was 8 when his father left, and now he was 15. David was 13 and Leslie — practically a baby back in 1966 — was 11. McDaniel took his wife in one arm and swept his daughter up with the other. The crowd at the Portsmouth Naval Hospital cheered. Many — including the media — cried. It was a picture-perfect scene.

McDaniel would spend several weeks in the hospital to fully recover physically. His transition into his home was slow and deliberate (seeing bright colors after six years of gray was hard to get used to). But soon, life began returning to normal. Upon his return, he received the Navy’s second-highest award for bravery, the Navy Cross; as well as two Silver Stars, the Legion of Merit with Combat “V,” the Distinguished Flying Cross, three Bronze Stars with Combat “V” and two Purple Hearts for wounds received while in captivity. He returned to the Navy and served as the commanding officer of the USS Niagara Falls in 1975 and ’76 and was commanding officer of the aircraft carrier, USS Lexington, from ’77 to ’78. He would go on to serve as director of the Navy/Marine Corps Liaison to Congress in the late 70s and early 80s before retiring in 1982.

But his most important work would come after retirement, speaking on behalf of the men he believes were left behind in Vietnam and creating the American Defense Institute, a nonprofit organization built to increase public awareness of the need for a strong national defense. He ran for Congress in North Carolina in 1982 as a Republican, losing to Democratic incumbent Charles Orville Whitley, and in 1988, he went on a national speaking tour of U.S. Navy commands to encourage military personnel to vote and to speak on his experience as a POW. At 86, he still speaks at public events. He still receives letters from around the world. And despite his fight, he still loves his country.

As they have several times on this day, McDaniel’s thoughts go back to Lt. James Kelly Patterson as we’re winding down. He recalls Patterson’s skill — he could hit a target within 15 feet from thousands of feet up. He was the heart of the A-6 aircraft. McDaniels says he was “just the pilot” — give me a banana and tell me where to steer.

He reveals that Patterson’s dream was to be a pilot himself. Bad eyesight kept him out of the cockpit, however. On one five-hour flight across the ocean, McDaniel surprised his friend by swapping seats with him shortly after takeoff (really difficult to do in such cramped space), and Patterson flew for four hours before the two switched seats again before landing. Had they been caught, it would have been a costly reprimand.

But McDaniel shared that story with the Pentagon after his return when they asked him for three things for their records that only Patterson would know. The happy story trails off into sadness.

“He’s probably angry for what he’s had to do,” McDaniel tells me. “His mother and father died without knowing what happened to him. And I’ve seen what it’s done to his brother. It’s just a sad situation.”

And this is how the interview ends. I have another five hours-plus ahead of me on the road, and it’s getting close to dinner time for the McDaniels. Dorothy invites me to stay over and use a guest bedroom. She insists, in fact, after I turn down the offer a few times. When Mike reminds her she’s asked me five times already, she replies, “Well, I’ll ask him a sixth time.”

Red McDaniel grabs a few hardback copies of Scars & Stripes and signs one for me and another for my father-in-law, who served in the Navy and was aboard the USS Ranger during combat operations in Southeast Asia in 1966. The family tells me I have a place to stay the next time I bring my family up to visit Washington, D.C. — an incredibly kind gesture, considering how loud my kids are and the fact that I’ve known them less than four hours.

Mike McDaniel walks me to my car in front of the house. We talk a little about his parents and what exceptional people they are. He says earlier that one of the things he learned from his father and his experience was forgiveness. The fact that his father could forgive the men who beat and tortured him sticks with him to this day.

Outside, we talk about the other message that resonates. He tells me he lost his son over two years ago. The car he drives today — the one with a Philadelphia Eagles sticker on it that I poked fun of earlier before I knew better — was his son’s. Mike and his family were able to deal with this tragedy because of the experience and the lessons learned from Red McDaniel’s capture in Vietnam 40 years earlier.

“We’ve all had tragedy in our lives,” he says. “My father set the example with his belief that in all things, God works for good. We’ve seen that in our lives. When I lost my son, my dad told me, ‘Michael, this is a tragedy, and I can’t take that hurt away. But from my perspective, if I had known God would use what I went through in my captivity to eventually help people, it wouldn’t have made my captivity any easier. But it made it worth it. There will be good from this. I can’t explain how, but there will.’

“I see it,” Mike adds. “Even just going through all of this again talking with you today, it brings back how blessed we are that we’ve had him home all these years. We’ve also had a chance to see the fruit from it. God’s promise in His word is definitely true.”